Yesterday morning I walked down to St. James Cathedral bearing my camera gear like a giant question mark. I wanted to see if I could discern what makes Rob Ford tick—not Rob Ford the man, obviously, since he’s no longer with us, but Rob Ford the cultural phenomenon.

I went with a theory: that Rob Ford is an accidental postmodern. The way I understand postmodernism, it began as an intentional critique of the relationship between power and culture and supplemented its theorizing with a set of practical tools for subverting that relationship. It challenged the hierarchical structure of cultural production. The distinction which privileges high art over pop culture is a false distinction. So, too, the distinction which privileges scientific/academic discourse over lay inquiry. Professionalism over the amateur. Religious orthodoxy over grassroots spirituality. Reason over dreams. White over black. Man over woman. Straight over queer. Not surprisingly, the earliest theoretical glimmers of postmodernism coincided with the rise of practical movements: Black Power, Feminism, Gay Rights.

More recently, we’ve witnessed the emergence of cultural phenomena which, while never intended to fulfill a postmodern agenda, nevertheless bear some of its marks. They are accidentally postmodern. Facebook is a good example of this. It has ripped down the walls between our neatly compartmentalized discursive habits. Now, it’s hard to tell whether we’re reading news or advertising, gossip or fiction. Facebook makes it impossible to privilege one discursive mode over another. (The only thing that’s privileged is Facebook itself.) In the same way, Rob Ford never woke one morning and said to himself: Hey, I’m gonna be a postmodern mayor. It just happened that way.

Consider the evidence (or don’t, since that might be too scientific). Ford occupied the office of mayor which, traditionally, evokes a sense of gravitas. The mayor is addressed as Your Worship, and he has all the powers of a Justice of the Peace which entitles him, among other things, to preside over marriages. Tradition treats it as an office marked by dignity. People loved Ford for the fact that he was accessible and casual. He was hands on. Accessibility may have come at the expense of dignity. Everybody knew he was smashed on the job. Everybody knew he worked while driving. Talked on his cell phone while driving (gave a woman the finger when she told him to hang up). But so what? He demystified the aura that enshrouds the mayoral office.

He blurred lines. With him, it was impossible to tell whether he was politicking or entertaining. The conflict of interest scandal that nearly cost him his job underscores this blurring of lines. He didn’t appear to understand that it might be inappropriate to solicit funds for a personal charity on City Hall letterhead. But why should he when such distinctions belong to an earlier time with its archaic assumptions about propriety? Or consider his personal wealth which suggests white male privilege. And yet he styled himself a man of the people. A mayor for the little guy, enormously popular with working class and Black voters. Never mind his union busting, his racist rants, his groping and butt patting, his refusal to attend LGTQ events. One could call him hypocritical or contradictory. But I wonder if, maybe, he occupied a Both/And cultural space that gave him an extraordinary sense of freedom.

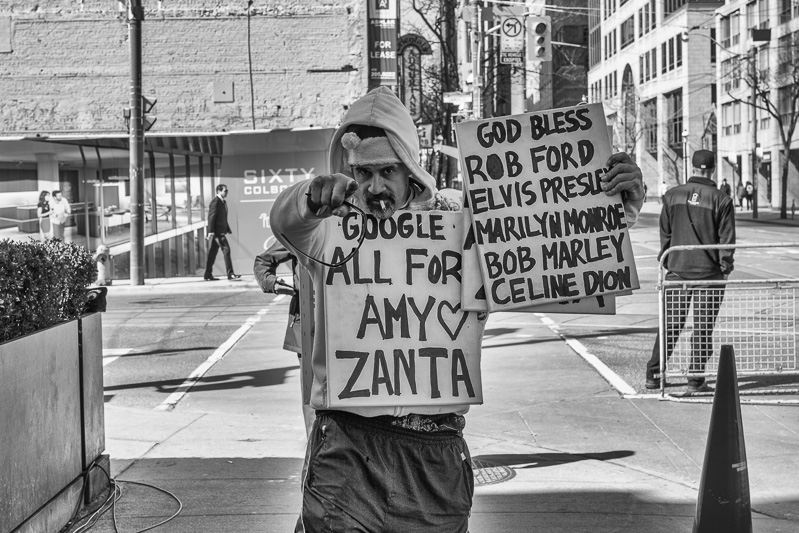

At Jarvis & Adelaide, I cut through St. James Park. I remember when this was a tent city during the Occupy Movement. Although I was early, a line had already formed in front of St. James Cathedral, members of the public hoping to get inside for the funeral. I crossed to the south side of King Street and positioned myself across from the front door. Beside me, the media had set themselves up, talking heads, live commentary, drooling experts. A man in shorts and a Santa Claus hat was posing behind them. I laughed. It seemed perfect. I squinted at the man with his goatee and cigarette. Wait a sec. Isn’t that Zanta?

Have you heard of Zanta? He’s something of a fixture in these parts. You can read more about him on his wikipedia page, but the short version is that, 16 years ago, he fell down a flight of stairs and may have suffered neurological damage. He was later diagnosed with schizophrenia. His name is David Zancai, but he has adopted the performing name of Zanta. His performance involves wearing a Santa hat, doing a lot of push ups, posing (totally ripped), and wishing people a Merry Christmess on any day of the year (except Christmas).

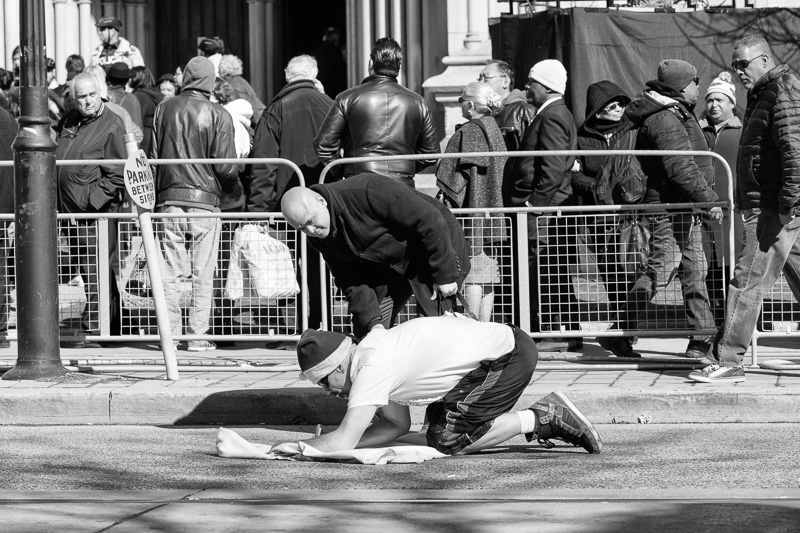

Zanta lay down on the street in front of the church and started doing pushups. When he finished his pushups, he lay his sweatshirt on the pavement, pulled out a magic marker, and started writing a message on it. Three police officers stepped onto the street and encouraged him to leave, forcing him to the eastern edge of St. James Park where he simmered for a time on a park bench. I spoke to the police officer who led the push to expel Zanta. If I was going to play amateur photojournalist (or whatever the hell I thought I was doing), it seemed a good idea to do some fact checking. The police officer confirmed that, yes, the man is Zanta. He rolled his eyes. He’d had dealings with Zanta for probably 10 or 12 years now. But they had to get him out of there. It was important for the funeral to go off with some decorum.

Later, I spoke to Zanta. He was pleased to hear that my name is David. He asked me if my parents are alive. Yes. Grandparents? One. How about the other ones? Well, um, uh, no (logic didn’t appear to be one of his strong suits). He said he’d tell me where they are. His rambling boiled down to this: my deceased grandparents are with Rob Ford. No doubt they’re delighted to have his company. He talked in a wandering way. It wasn’t an associative wandering. More a string of non sequiturs. It was impossible to have a rational conversation with the man.

The pipers piped. The honour guard marched. The hearse arrived and pulled to the front door of the church. And behind it all, the rabble. People with their signs and little flags declaring their allegiance to Ford Nation and proclaiming Rob Ford the best mayor ever. They were loud and unruly. They shouted their non sequiturs, their contradictions. I turned and Zanta was gone. I caught sight of his white hood disappearing into the mob. He fit right in. So much for the police and their decorum.

It would be easy to ridicule the Ford Nation phenomenon. I was born into a modern world, but educated into a postmodern sensibility, so I tread on fractured ground. The reasonable me, the one who likes neat categories and well-reasoned arguments, would very much enjoy running Ford Nation through my privileged blender. But the unreasonable me recognizes that my reasonable upbringing is intimately tied to stories of unjust relations. With time to reflect on the photos I took of Ford Nation’s citizens, I’m reminded of the Black Lives Matter tent city at Police Headquarters. These are not two separate groups. They merge like a Venn diagram. Their points of intersection are messy but they need to be acknowledged. As for Rob Ford, I wonder… Privileged white man with a penchant for hypocrisy? Or could he, indeed, have been an ally? And what does that make me if I dispute those who claim he was?