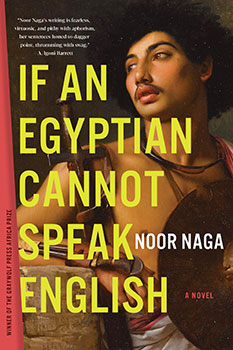

Noor Naga, best known for her poetry, has written a novel that is a 2022 finalist for the Scotiabank Giller Prize. I think it is relevant that she is a poet, as her poetics leak into her prose, giving it a compression and density that is sometimes dizzying. By that, I mean that her relatively short novel offers up far more than one would expect in this space.

The book has an eccentric three-part structure. The first part takes the form of a catechism: question followed by a paragraph offered as an ostensible response. Each paragraph of the catechism alternates between the perspectives of a poor Egyptian youth from the small village of Shobrakheit and an American girl of Egyptian descent who has come to Cairo for reasons that remain vague perhaps even to her. With each paragraph, we find ourselves proceeding incrementally into an unhealthy co-dependency that finally blossoms into a full-on abusive relationship. Think Elizabeth McNeill without any of the erotic rewards.

Each character feeds the other. The youth, known only as “the boy from Shobrakheit” has the insider’s knowledge of life as an Egyptian; he is a native Arabic speaker with the native’s understanding of cultural nuance. The American girl, named Noor, says “I’m caught between my desire to understand and my desire to appear as though I already understand.” The boy answers that desire. Meanwhile, the boy is poor and struggles with a cocaine habit. Although not rich by North American standards, Noor’s money goes a long way in Cairo and it supports Noor’s impulse to “rescue” the boy both from his poverty and from his habit. Just as each gift is an occasion for desire, so it is paradoxically an occasion for envy and resentment. Noor, envies the boy for the ease with which he crawls inside local life. Meanwhile, the boy envies Noor for her privilege (both financial and linguistic) and the mobility that gives her.

The second part of the novel continues the alternating paragraphs, but without the questions that open each paragraph. Questions belong to the beginning of a relationship when each party is still eager to learn as much as possible about the other. Here, the relationship has come apart. The boy stalks Noor. Every day, he climbs a bridge which gives him an unobstructed view into her apartment. Meanwhile, the text is sprinkled with footnotes that deliver arcane facts about local customs, as if to suggest that Noor is finding her own way without the local boy’s help. So, for example, we learn about ful, and how a kherty is a man who provides certain services to foreigners, and we learn about cheap outdoor cafés called awhas. As in the first part, each new paragraph brings the characters incrementally closer to one another. However, where the prospect of a new relationship held some excitement, now the prospect of its renewal holds only dread. Without giving too much away, the dread proves warranted.

The first two parts are set against the backdrop of another abusive relationship: that between the people of Egypt and their political leaders. Following his grandmother’s suicide in 2007, the boy from Shobrakheit left his village and made his way to Cairo. There, he witnessed the Arab Spring of 2011 and even made some money selling photos to press agencies. Mubarak was deposed and ultimately el-Sisi replaced him through a popular election. However, whatever hopes the Arab Spring inspired have since been dashed. We saw, for example, how social media, especially Twitter, were touted as the great tools for grassroots organization. But we have since discovered how easily the same tools can be used for mass surveillance and the subversion of civil liberties. In the same way, people hoped that the democratic process would produce a just society. Instead, they got el-Sisi, another authoritarian who is probably worse than Mubarak. The novel’s present time is 2017 just before el-Sisi’s election to a second term.

The third part of the novel offers an odd twist. The novel appears to be done, and we now have the transcript of a session at a writer’s workshop where students comment on Noor’s work. This has a destabilizing effect on the reading, as it’s difficult to know where the limits of the novel lie. Is it over? Is the transcript a “bonus” feature, like the discussion questions for book clubs that appear at the end of some novels? In fact, I was reading the novel on a Kindle and when I reached the end of the second part, the “rate this novel” feature popped up as if to signal that I was done. It was difficult to tell whether this was a deliberate measure to support Noor Naga’s destabilizing strategy, or whether the ebook designer had simply fucked up.

I closed the “rate this novel” feature and read on. In the writer’s workshop transcript, we learn that this is not a workshop for novels at all, but for memoirs. Noor (the character) offers her book as non-fiction and the students discuss the relative merits of the devices she has used to recount her lived experience in an abusive relationship. There is the “catechism” of the first part, and the footnotes of the second part. But perhaps the most problematic device (at least from the perspective of some women in the workshop) is Noor’s decision to give a voice to the abuser. Why should she (or we) care what an abuser thinks? In our post #MeToo world, isn’t it our duty to foreground the victim’s voice?

It is at this point that Noor Naga poses interesting epistemological and ethical questions. First, her destabilizing strategies don’t stop at the edges of the novel, but go on to self. Is the self a unity, or is it porous, in a co-dependant relationship with the wider world of language, culture, social milieu, politics, history? In a world of fluid identity and interpenetrating consciousness, how far can we push the novelistic trope of the unique and uniquely named character before it ceases to be a useful representation of how we experience selfhood in our lives?

Second, working at cross purposes to this epistemological musing, we land on the ethical question of whether it is justified for a person, a writer, say, to enter into the lived experience of any other person. Maybe the attempt to represent the interior lives of others is an intrusion or, worse, the expression of a neo-colonial impulse. The novel is a chain the writer uses to shackle others whom she exploits by monetizing their experience. The ethical question asks whether a writer ought to represent anything save her own lived experience, effectively turning all writing into memoir. Meanwhile, the epistemological question asks whether such ethical strictures are even possible, effectively turning all writing into fiction.

Within the novel itself, the American girl confesses that when she was younger she was radicalizing into the worst kind of SJW:

I was vindictive. I was egomaniacal and mean. I was accusing elderly white passengers on the train of racism or gentrification and live-streaming their reactions, to uproarious virtual applause. I was sharp as my toothbrushed edges, big as the teased-up afro I eventually shaved so as to pass at the gay bars I had begun to frequent as something of a Twitter celebrity. This is the question I get once a week in Cairo, now that it’s clearer to people I’m not ill: Why did you shave your head? The answer as Manhattan as I am: identity capitalism. Because I wanted to win by appearing to have lost, because queerness is a spectrum, and no one can say I’m not. [italics in original]

This may offer an answer to the workshop critics in part three who worry about Noor (the character) giving voice to the abuser. The extreme activism practised by SJW’s tends to be self-righteous and is absolutely certain in its insistence on a purity of personhood. This insistence aligns the SJW with the ethical strictures noted above that insist we can write about interior experience only if it is ours. But it falls afoul of the epistemological observation that such strictures are probably impossible. The good news of this observation is that, given the porous nature of personal identity, we are in all likelihood hardwired to empathize with experience that’s not our own. For that reason, we might want to refrain from giving artists grief when they try to give that impulse free play in their work, even when they encourage empathy with people we don’t like.

I wonder if the meta quality of the third section isn’t a strategy for Noor (the author) to shield herself against the very criticisms leveled against Noor (the character) in the writer’s workshop. She gets to answer her critics by saying: yeah, I’m aware of the problem inherent in representing the interior experience of bad people, but, hey, it wasn’t me, it was my character.

Noor Naga is an intelligent writer who crafts wonderful prose. I hope this book signals the beginning of a long and fruitful run. In future novels, I’m confident she can dispense with the defensive meta strategies and simply get on with the business of presenting deliciously complicated and nasty characters. From Raskolnikov down to Teju Cole’s Julius in Open City, the literary canon is full of assholes who warrant our attention. But there’s always room for more.