The other day, in a friendly argument with my father, I took the position that there is a greater cultural divide between him and me than between me and my children. My father is 27 years older than me and I am 27 years older than my son, yet (as I contended) I have a greater affinity for the world my son inhabits than my father has for the world I inhabit. My son and I like to listen to the same music. It sounds the same to our ears. If he discovers a new indie band and wants me to listen, I find myself drawn to it for the same reasons that attract my son. He often hits upon offbeat films and introduces them to the rest of the family. We watch together and when it’s done, we realize that we share the same aesthetic sensibilities. This is also true of the books he encounters in new curriculum for his English classes. Typically, they’re books I’m familiar with and we “get” them in the same way. Oftentimes it feels like we are cultural peers.

However, I don’t have the same sense with my father. Sometimes, when my parents go on holidays, they leave us with tickets from their theatre and concert subscriptions—things like Doc Severinson, the Boston Pops and Rob McConnell and the Boss Brass — all great musical acts, but none of them will ever take me above lukewarm. The closest we’ve ever come to a synchronicity was a Johnny Cash/June Carter concert at the old band shell at Exhibition Place when I was six, an outdoor concert in the pouring rain. There was a Gordon Lightfoot concert, too, at Massey Hall, and let’s not forget the Arlo Guthrie concert at the old Ontario Place forum. But for the most part, our tastes have sat on either side of a fairly rigid divide.

I’m not sure why this is. Part of it may be incidentally related to technological change: it’s far easier for me to adapt to the pace of change which my son assumes as normal than it is for my father. But I leave that to another post. I want to focus instead on the fact that my father and I sit on either side of the sixties. When I observe the generational dynamics in my own family, I wonder if we are only now beginning to witness the full extent of the cultural upheaval that occurred in the sixties. Think of the pill and the sexual revolution, the beat poets and the blurring of lines between high and low culture, rock ‘n roll, the anti-war movement and the “normalizing” of social activism, civil rights, feminism. The legacy of that period is a heightened level of engagement in pop culture and politicization of social concerns.

My father graduated from his teens before Jerry Lee Lewis ever sang “Great Balls of Fire” and he was a father by the time the Beatles invaded America. Although he studied on an American campus in the sixties (I do have memories of this time), he was the serious guy with the short hair and dark-rimmed glasses. He never smoked a joint (that I know of) or wore a tie-dyed shirt or said “far out” or “groovy”. I remember evenings in our off-campus townhouse in Syracuse, NY watching a black and white TV—shows like Laugh In and Ed Sullivan, but that was about as far out as we ever got.

Born before the war, my father remembers carting a wagon around Yarmouth, N.S., gathering scrap metal to do his bit for the war effort. Even kids knew that they could make a difference. The Second World War provided a unity of purpose that, at least in North America, produced a social cohesion and cultural hegemony that we haven’t witnessed since. As a teenager in the McCarthy era, that social cohesion was reinforced by fear. My father’s social and political orientation to the world was formed with the Cold War as a backdrop; mine, with the disillusionment of Viet Nam’s failure and the rise of the Khmer Rouge. Optimism vs. pessimism, universal values vs. cynical realism.

The extent of this divide was driven home to me recently when I stumbled upon some Mad Magazine cartoons from the Cold War era. They purport to poke fun at Russia, but they reveal far more about the West. Half a century later, many of the underlying cultural assumptions emerge for us with painful clarity, and current events stand as illustrations of the lies we once told ourselves.

Report To Russia

Ivan Slobotnavitch, Ace Moscow news correspondent, was recently assigned to photograph and report on the shocking conditions prevalent in this decadent capitalistic country of ours. He arrived here armed with camera, film, pad, and pencil (red), and went straight to work. Fortunately, MAD was able to intercept the dispatch Ivan sent back to Pravda. Here, then, is the United States as seen through red-tinted glasses in Ivan’s … Report To Russia.

The Russian journalist is typed as a buffoon with antiquated photographic equipment and a bottle of vodka hanging out of his pocket.

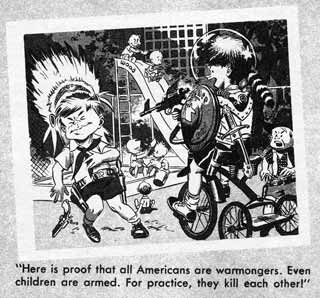

This was supposed to be a joke! Now, with yet another unwinnable “war” under its belt and more than a million civilian casualties to account for, the humour is lost on us. Note how the kid with the coonskin hat is shooting the kid with the feathered headdress, replaying the myth of imperial domination that has come to be America’s foreign policy trademark.

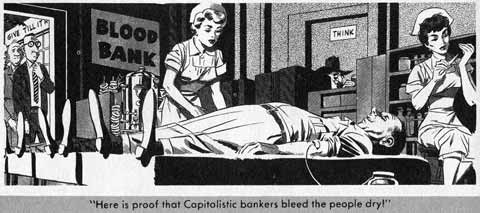

Bankers bleed us dry? We are supposed to chuckle to ourselves and say: “But of course we know better. Bankers are our friends. They loan us money so we can be good consumers and grease the wheels of our economy.” What would the gag look like if the cartoonist could have anticipated a future with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and subprime mortgages? Who could have foreseen that, rather than bleeding us dry, bankers would lend us to death?

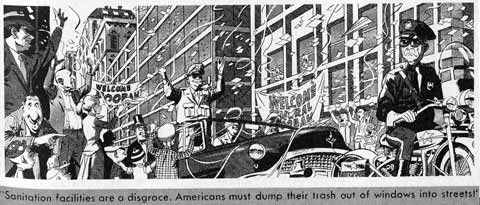

A Douglas MacArthur lookalike in a tickertape parade? A comment about waste disposal? Is this cartoon a commentary on militarism or consumption? Is there a relationship between the two? What was the shared point of view that allowed Mad readers to “get” this joke. How funny is it today to celebrate military conquest by dumping our surplus out the window? And post 9/11, what kind of associations does it conjure up to see debris falling between tall buildings?

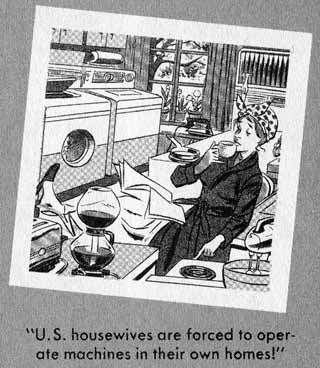

In a cartoon which predates feminism, the word “forced” is revealing. Although intended with humourous irony, many women didn’t see anything funny about being relegated to the role of launderer no matter how many automated conveniences their men brought home. Note how she’s sitting with her feet up, not yet dressed, sipping a coffee, as if women have nothing to do all day. This also illustrates a conventional view of the day that modern conveniences would give us more time for leisurely pursuits. In fact, the opposite has proven true, and 21st century North American households are a blur of frenetic activity that leads to burnout and exhaustion.