The old house was the same, droopy and sick, but as we stared down the street we thought we saw an inside shutter move. Flick. A tiny, almost invisible movement, and the house was still.

Somebody cut a few sentences from Harper Lee’s novel, To Kill A Mockingbird, and pasted them to the side of a booth in a parking lot. Why would they do that?

I like to get up in the morning and follow more or less the same routine every day.* Mostly I get dressed by starting with my underwear, though, if I throw caution to the wind, I might start with my socks instead. I eat my cereal with a sliced banana on top and wash it all down with a glass of grapefruit juice and a mug of black coffee. I eat my lunch at noon and my supper at six. I go to bed at eleven so I can have a good night’s sleep. I like the regularity. It never occurs to me that I could disrupt this well laid pattern by snipping up a novel and pasting bits of it onto carefully selected surfaces. It might make me late for lunch.

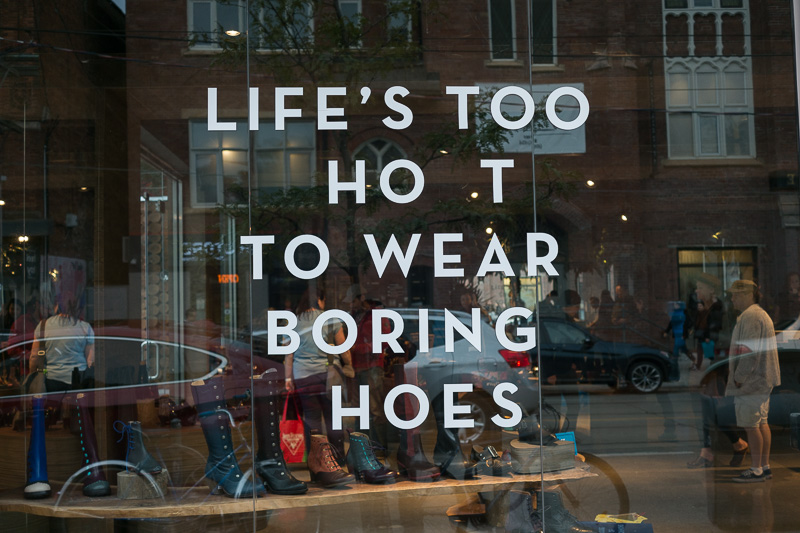

In the same way, it never occurs to me to stay up past my bedtime, sneak through the dark streets, and peel selected letters from a shop window so the remaining letters offer an entirely different message.

I think it has something to do with the 2nd law of thermodynamics. I’m a closed system with no energy from outside sources, so I wind down as the energy dissipates. One day, I’ll be old and doddery. I’ll hobble around on a cane and yell for everyone to speak up. People who design and print stickers of stylized hotdogs, then run around the city looking for places to stick them, are people who have mysterious reserves of energy. Their creativity defies the fundamental laws of the universe. They are demi-gods creating ex nihilo. They are ageless.

But the execution (of a creative plan) accounts for only half the energy. Before the snipping or the peeling or the designing or the printing or the running around, there’s the imagining. There’s the decisive moment when a person says “aha, I could really DO that.” For ordinary mortals, that imaginative act draws GigaWatts from the grid, but for creative demi-gods, the “aha” moment arrives with a lightning bolt and, for that reason, has its own power supply. Even the simple act of giving a stone figure a cigarette catchlight leaves the traces of an autocatalytic impulse.

Something you should know about random acts of creativity (RACs for short): they haven’t been vetted or approved or officialized by an authoritative curator type. That means not everybody is happy to see their appearance in public spaces. If RACs could be curated, then everybody would be happy because they would have the assurance that, somehow, the RACs had a proper place in the big picture; they might even have an economic rationale which, no doubt, is the true raison d’être of all creative undertakings.

Something else you should know about RACs: they are ephemeral. One day, I passed a brilliant treatment of James Dean. The next day, I passed and it was gone. Someone in authority had obliterated it with whitewash. Why do we put up with such vandalism!

These ephemera are the shadows of consumerism. Like all consumer goods, planned obsolescence is written into their DNA. Some of them shine at us like glossy advertising. We note them with a two-second flick and then they turn invisible to us. We become desensitized to their impact, just as we lose our urge to spend money once a marketing campaign has petered out. What are we being asked to buy? What urge are they stimulating in us?

________________

* I apologize for the redundancy: “more or less the same” is what makes it a routine. (I apologize doubly for the incoherence: nothing can be “more or less” the same; either it is or it isn’t.)