Before I introduce the 4th installment of my January Book Project, let me tell you about my great uncle Perly. My great-grandfather Fred had four sons. The oldest was Bert who test-drove cars in Detroit during the early days of the automotive industry. The second and third, Ralph and Reggie, became ministers in the United Church of Canada. Both had doctorates and were venerable theologians. Both were humble men, and while I can’t speak for Reggie, I know that Ralph (my grandfather) was a pacifist. And then there was Perly. My great uncle Perly was an engineer who moved to the U.S. and was a pioneer in the field of refrigeration. To all those people who went out of business supplying ice for ice boxes, I offer my great uncle Perly. They have him to thank for their bankruptcies. Unlike his three older brothers, Perly did well for himself. I suspect he held a number of patents on components for appliances that you and I still find in our kitchens. He and his wife retired childless to a cushy residence in upstate New York.

And then.

And then his adopted country summoned him to perform a special service. The U.S. was spearheading a U.N. coalition to drive the Iraqis out of Kuwait—Operation Desert Storm. They would send more than half a million troops into the desert and they needed refrigerators. It sounds silly, but that’s more or less what it boiled down to, or would have boiled down to if they hadn’t set up their refrigerators in the desert. The DOD was sending its boys (and its girls too) into battle, and when those troops came back from a hot day in the desert, the DOD was gonna make damn sure they got ice cold Budweisers to wash down their char-grilled hamburgers. The DOD commissioned my great uncle Perly to design colossal refrigeration units, desert freezers so big you could almost see them from space, so that not one of those half a million American soldiers would be denied his god-given right to drink beer and eat burgers after a long day of hunting Iraqis.

My grandfather was more than a little miffed when he heard that his brother was selling his services to the U.S. military. I’m not sure what my grandfather felt. Betrayal maybe? The four brothers had been raised in an idyllic setting on the banks of the St. John River. The desert of Kuwait seems a long way from the old whitewashed church in Sheffield. When my grandfather heard what Perly was doing he had just been diagnosed with cancer. I don’t think the brothers met or even spoke before my grandfather died. Later, my father visited Perly. He was the eldest of the nephews and far less inclined than my grandfather to judge the man. I suspect my father visited Perly because he was the last of his generation. Maybe my father was seeking a sense of connection.

I have no idea if anything I’ve just written is true. Maybe I’ve made it all up, a constructed reality to serve my own needs. It’s vaguely accurate, but there’s so much of it that lies hidden from me. Did Perly travel to the middle east? I think he did, but maybe all that was required of him was to sit at a drafting table in his basement. What kind of clearance did he have? I imagine a photo in his office: him shaking hands with George H.W. Bush. But maybe he only got to deal with low-level bureaucrats at the Pentagon. Those unknowns are trivial beside the unknowns of the mind and of the heart. At the end of his life, how did my great uncle understand himself in relation to the child who grew up in rural New Brunswick? How did he rationalize the gulf between himself and his brothers?

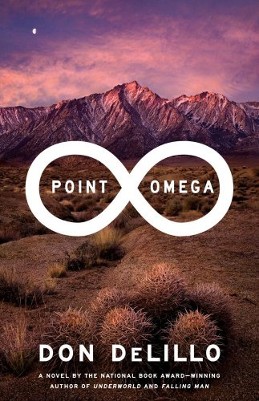

This is the kind of story that tempts me to write a novel. I see in it a grand metaphor—bringing ice to the desert. It suggests a heinous colonization, sucking the heat from the desert so that men can march cold over the sand. Maybe some day I’ll write it. In the meantime, we have Don DeLillo‘s Point Omega.

The main character of Point Omega is Richard Elster, a defense intellectual, an academic recruited by the DOD to “freshen the dialogue, broaden the viewpoint.” Like my great uncle Perly, Elster approaches problems conceptually. He abstracts himself from the gritty reality his work supports. We never learn precisely what it is that Elster contributes, but we suspect that he is the secular equivalent of an evil priest, rationalizing abuse so that powerful men can sleep easy at nights. He freshens the dialogue by offering euphemisms, but the result is anything but a broadened viewpoint. It is a “makeshift reality” that is a closed system.

In the novel’s present time, Elster has retired to a crumbling home in the desert. A much younger man, Jim Finley, seeks him out to participate in a project. Finley is a filmmaker. He wants to produce a documentary: Elster in front of a blank wall, talking, one take, no edits, no questions, no soundtrack or cuts to supplementary footage, only Elster offering a bald statement of the truth. Finley’s encounter at the desert home reminds me of my father’s visit to my great uncle Perly’s home. Finley doesn’t approach Elster with judgment; only curiosity.

Elster has retired to the desert to escape “the usual terror” which is the feeling he gets when he experiences time as it’s reckoned in cities:

It’s all embedded, the hours and minutes, words and numbers everywhere, he said, train stations, bus routes, taxi meters, surveillance cameras. It’s all about time, dimwit time, inferior time, people checking watches and other devices, other reminders. This is time draining out of our lives. Cities were built to measure time, to remove time from nature. There’s an endless counting down, he said. When you strip away all the surfaces, when you see into it, what’s left is terror. This is the thing that literature was meant to cure. The epic poem, the bedtime story.

The duo becomes a trio when Elster’s grown daughter, Jessie, joins them in the desert. She, too, is a refugee from the city. Her mother has forced her to come here. Jessie has a boyfriend whom we never meet, but he is an ominous presence. Jessie’s mother has been receiving phone calls from someone who never speaks and blocks his caller ID. She knows it’s Jessie’s boyfriend and she knows he’s a threat. She doesn’t know how she knows, but she knows.

I’m not sure, but I think the omega point refers to the point at which the inanimate universe becomes self-aware. It is more than simply being human. It is more than being conscious. It is “[a] leap out of our biology.” Maybe DeLillo is talking about our existence as spiritual beings, our souls. But the omega point is more like a fulcrum in that it can teeter in either direction. Yes, there is a sense in which matter yearns to become self-aware. But things can tilt in the other direction too. “Consciousness is exhausted. Back now to inorganic matter. This is what we want. We want to be stones in a field.”

Jessie vanishes. The Sheriff’s office sends a search party into the desert. They recover a knife, but no trace of blood, and certainly no body. With a stalker boyfriend lurking in the background, there is an intimation of foul play. But it feels like Jessie’s disappearance is not to satisfy the demands of plot, but to satisfy whatever law the omega point represents. Her consciousness is exhausted and must be pulled out of the novel.

In a sense, Point Omega the novel, teeters on the fulcrum of the omega point just like the characters within its covers. It yearns to affirm its self-awareness. Not the crass clichéd sense of a novel about people who suspect they are characters in a novel. DeLillo is too subtle for that. He frames the novel with the presentation of an art installation that appeared at the Museum of Modern Art in 2006, 24 Hour Psycho by Douglas Gordon. The installation takes Alfred Hitchcock’s 109 minute movie, Psycho, and slows it to approximately two frames per minute so that it takes twenty-four hours to view. In this expanded time, we no longer experience “the usual terror.” Maybe we experience an unusual terror.

There is an unnamed man lurking in the gallery, coming day after day and standing all day watching from the shadows, counting the number of rings on the curtain rod after Janet Leigh tears the shower curtain when Norman Bates stabs her. The man watches the knife slash the woman’s flesh in slow measured strokes. “The film made him feel like someone watching a film.” A work of art which appropriates another work of art, itself becomes appropriated in a work of art. The novel makes me feel like someone reading a novel. It leaps from its own lexicography. Point omega.