My Grandmother died on April 20th. I’ve never been present before when a death is declared. My grandmother had obviously expired, but the attending VON lacked the necessary government-approved certification to say unequivocally that she was dead. At times like this, I become strangely practical. I suggested we turn off the oxygen machine (why waste perfectly good oxygen?), but the VON said no; we needed to wait until his supervisor arrived and declared the death. To my mind, these strict procedures could mean only one thing: some time in the past, a well-meaning relation had turned off an oxygen tank and inadvertently suffocated his grandmother who wasn’t in fact dead but only appeared to be dead. I pulled my hand from the machine and sat like everyone else, waiting for the supervisor to show up. I had to pee but didn’t move. I was afraid tinkling sounds might disturb the solemnity of the moment.

When the supervisor arrived, he did the usual things you’d expect. He felt the wrist for a pulse. Then the carotid artery. He pulled out his stethoscope and listened for a heart beat. Logically, it’s impossible to prove a negative proposition, in this case, that my grandmother was not alive. Everyone in the room—my parents, me, the VON, the supervisor—everyone knew that my grandmother was no longer alive. But how do you establish that as a fact? You want to avoid the Pythonesque situation where, on the way to the funeral home, the presumed corpse sits up and says: I’m not dead yet.

The day before, they had wheeled a hospital bed into my grandmother’s living room so she could die in comfortable surroundings. Now, as the supervisor followed his procedures, I sat to the west of her, on her favourite couch. As a kid, I had sometimes slept on that couch, but in the living room of the house on the family farm. As a teen-aged sci-fi geek, I had read Robert A. Heinlein novels on that couch. Later, as an English major, I read James Joyce’s Ulysses on that couch. Now, my grandmother’s body lay propped a little to one side, facing me where I sat. My parents stood to the east of my grandmother and so they missed what I saw next.

The supervisor asked for a Kleenex. My mom found the box and handed it to him. He took a Kleenex and rolled it to a point. He leaned over my grandmother from the far side of the hospital bed, with his back to my parents. He pushed back the eyelid of her left eye. My grandmother stared directly at me with her one unblinking eye. Her pupil was dilated, ringed around by the thin band of her blue iris. The supervisor tapped the cornea, once, twice, three times, with the tip of his rolled Kleenex. I don’t understand the physiology of it, but I guess he was looking for some kind of autonomic response. He didn’t find it. He shut the eyelid and scribbled some notes on his official declaration of death form.

At that moment, I couldn’t help myself. I guess it has something to do with my literary background. As I stared at my grandmother’s dead eye, I couldn’t help but think of Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart.” Near the beginning of the story, the narrator describes the old man’s eye:

It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain; but once conceived, it haunted me day and night. Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire. I think it was his eye! yes, it was this! He had the eye of a vulture—a pale blue eye, with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me, my blood ran cold; and so by degrees—very gradually—I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye forever.

Although my grandmother had died, still she stared at me. Based on that stare alone, I would not have been able to tell that she was not alive. They say (and by “they” I mean some impossible-to-identify person in the misty past) that the eyes are the window to the soul. But my experience suggests that the eye is a deceptive organ.

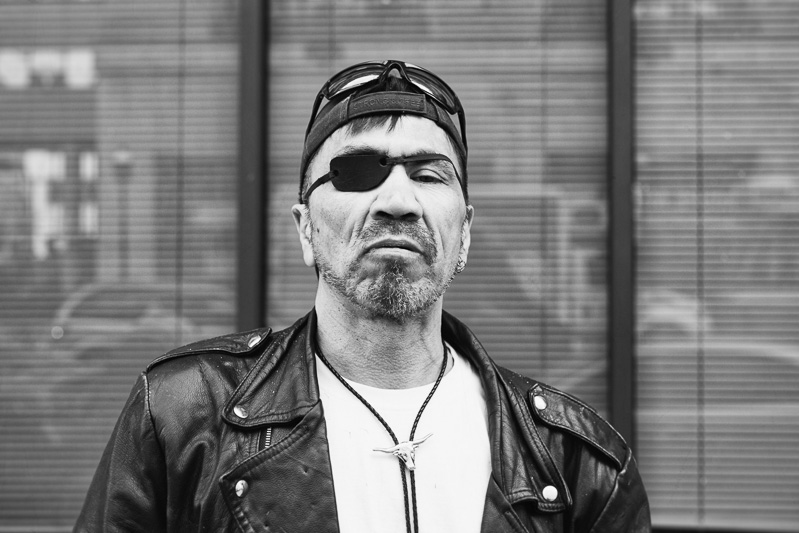

When I do street portraiture, the number one rule is: focus on the closest eye. As a result, I’ve become adept at manually shifting the active auto focus point into position as I’m yakking it up with prospective subjects. When I capture an expressive face and discover, in post, that the closest eye is perfectly crisp, I smile and give myself a pat on the back. I’ve got myself an image that viewers will care about. Inevitably, the image will draw their attention to the eye. They will stare into it and sense that, almost mystically, it reveals the inmost depths of my subject.

Diane Arbus observed: “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know.” I would suggest that her observation is doubly true of the eyes that appear in a photograph. When we stare at an image of a person’s eyes, maybe all we can know for certain is the content (the hopes and expectations) of our projections. We meet an elderly man. We observe the time-worn lines etched deep in his face. We think: he looks like wisdom personified. He squints and it looks to us as if he’s staring halfway across the galaxy. As photographers, we want to capture this look and share it with others. But when we talk to him, the mystery evaporates. The man is a moron. Or worse, an asshole. He tells dirty jokes. He says he has a stash of kiddy porn under his bed.

I would hazard that the eye isn’t a sensory organ so much as an aesthetic convention. When we look at a painting or photograph, its eyes tell our eyes where to look. We stare first at the eyes, then follow their gaze into the scene. It produces drama. It suggests the culmination of a narrative. What’s more, the presence of eyes tells us how to engage the work. If eyes are the window of the soul, then a representation of the eyes is a representation of the window of the soul. The eyes tell us that if we look closely, we will discover hidden depths. Just as a perspectival trick (first invented in the Renaissance) produces the illusion of three dimensions on a flat surface, so a moral trick produces the illusion of deeper meaning.

In his book, The Ongoing Moment, Geoff Dyer opens by drawing a thread through the history of photography: the thematic preoccupation with blindness. He suggests that blind subjects are the objective correlative of the photographer’s desire for invisibility. I don’t think it’s that complicated; I think photographs of blindness lay bare the moral trick. Unless there is something in a photograph that indicates blindness (in many of the early photographs Dyer examines, the blind person wears a sign that declares the blindness), the photograph is no less meaningful than one in which the subject is sighted. Photographs of blind people reveal that the functionality of eyes has no bearing on the effectiveness of a photograph. By extension, they play on our anxiety that photographs—and art more generally—may in fact have no deeper meaning.

As we sat with my grandmother’s body waiting for the supervisor to arrive and to declare the death, the VON spoke to my mother. Maybe the silence bothered him and he felt compelled to say something. He asked if my grandmother was a Christian. I rolled my eyes. While my grandmother was a regular at a local Presbyterian church, she never talked about her religious beliefs. As I later discovered while sorting through her belongings, she maintained a hefty stash of Bibles and they were all dog-eared. My mother nodded and the VON went on a riff about how Jesus’s resurrection was a promise from God blah blah blah. As the VON went on about Jesus, I felt anxiety descend like a fog upon the room. I stared at my grandmother’s body. After 97 years of life, is this all that remains? What if we have no deeper meaning?