I get migraine headaches. I’ve been getting them since I was 11. On average, I get about 18 each year. On average, I’ve always had about 18 each year. Although I experience minor variations in the symptoms, they play out in roughly the same way each time. The first migraine headache I had at 11 was no different than the migraine headache I had last weekend. I have no idea what causes them and only suspicions about triggers. I’ve never really noticed any patterns…until now.

I recently picked up a copy of Migraine Art: The Migraine Experience from Within by Klaus Podoll and the late Derek Robinson with a forward by the similarly late Oliver Sacks. It represents the culmination of a project to develop a collection of art produced by migraine sufferers to communicate the experience from inside the head, as it were. They organized a series of four competitions advertised through the British Migraine Association and sponsored by a pharmaceutical company. They received more than 500 entries from children and adults, amateurs and professional artists, often accompanied by descriptions of their experiences. These were adjudicated by both artists and medical people many of whom were also migraine sufferers.

Among other things, the authors hoped the collection would be of practical value, perhaps serving as a diagnostic tool, at the very least, giving non-suffering practitioners an appreciation of the fact that migraines are not ordinary headaches. Also, they hoped that the exercise of using artistic expression to communicate the experience would provide some therapeutic benefit, especially for the children who participated.

Reviewing the art, I realize how varied migraine experience can be from one person to the next. For example, my migraines invariably begin with visual aura. There are six types of aura, but I’ve experienced only four. Mine start with scotoma (holes in my field of vision where things disappear), followed by tunnel vision, hemianopia (half the field of vision is obscured), and concluding with fortification spectra whose outlines shimmer almost like electric arcs. Some people experience only scotoma, no numbness, no headache, nothing. Other people experience “Alice-in-Wonderland syndrome” where they perceive limbs and/or neck as longer than usual (Lewis Carroll was a fellow sufferer). Some perceive themselves as removed from their bodies.

After the visual aura, I experience numbness of fingers, face, and tongue, typically (though not always) on my left side. In the case of a severe headache, the entire left side of my body will be paralysed. My foot flops around like a wet fish; I’ve caught it in the door and not even noticed. After the numbness, there is a period of 5 or 10 minutes when I become aphasic. I can formulate words in my head, but when I try to speak them, I make no sense. People might think I was having a stroke. Paralysis and aphasia are harder to represent in visual art and so, understandably, far fewer of the pieces in the book try to represent these experiences.

Finally, the headache. There’s a scene in a Robertson Davies novel, The Rebel Angels, I think, where one character rams a knitting needle up another character’s nose and through his skull. If I don’t get my medication, that’s what it feels like for me and I go to the hospital. Usually, I have meds handy and everything is fine, but sometimes the headache starts in my sleep and by the time I wake up it’s too late.

As I leaf through the book, I wonder how I might represent the migraine experience with a photograph. I haven’t got an immediate answer to that question, but I do know that I sometimes I get a migraine headache while making a photograph.

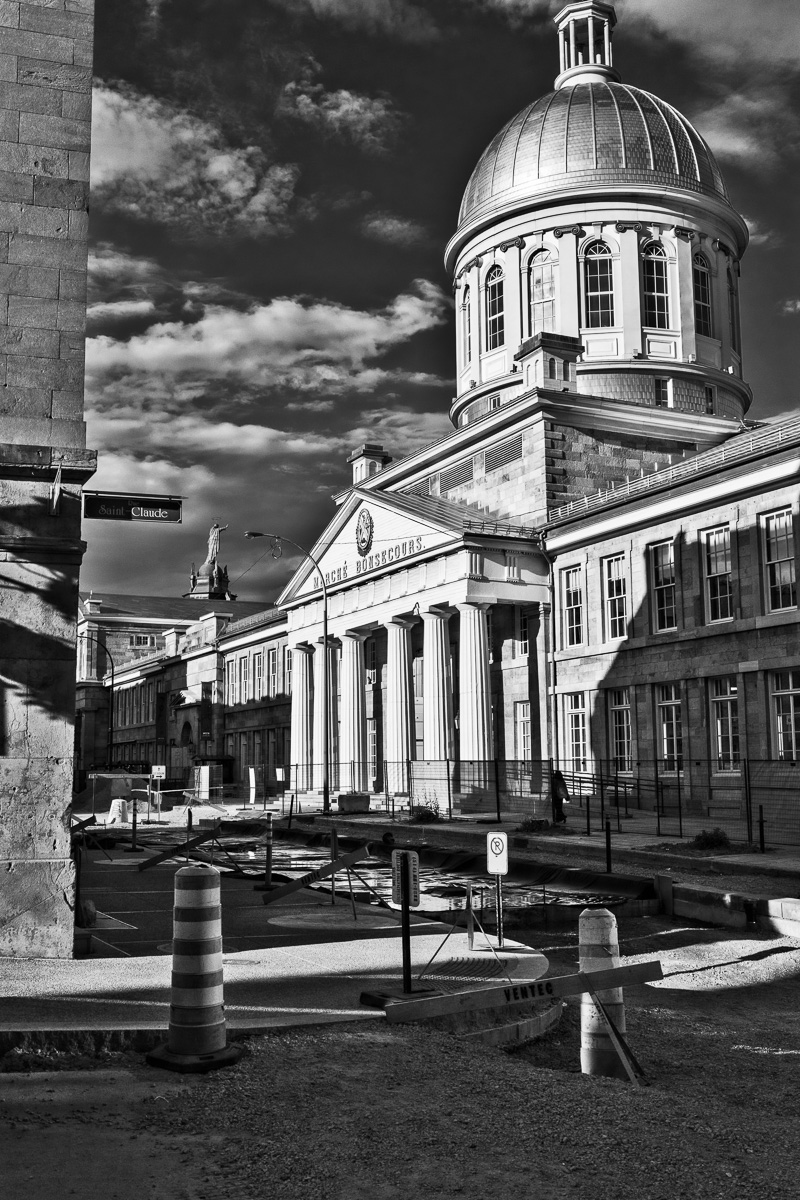

That happened to me recently in Montreal. One evening, we were walking along Rue Saint-Paul when I saw the low light striking the dome above the Marché Bonsecours. I paused to capture the moment:

The road had been excavated for repairs and there were hoses running here and there and I saw plumes of water spraying from tiny holes, presumably to keep the dust down. Puddles had accumulated in front of the building. I love puddles. If I have a camera in hand and I see a puddle, I’m like a 5-year-old. I have to go splash in it then crouch low to see what’s reflected in it. Here’s the shot I got when I ran to the puddles:

It was the right idea, but I thought I could take it further. I crouched. I stood up. I moved. I crouched. I stood up. I found something to stand on so I could look at things from even higher. I lay down on the ground. And so on … Boom. Oh shit. I stood up. Something had gone wonky with my vision. I looked at my fingertips and they disappeared. Classic scotoma. I rooted through my camera bag for my Imitrex. I take it as a nasal spray because delivery is faster through the nasal membrane. If I take a squirt within seconds of seeing the scotoma, I can minimize the headache; the next day, I might have a hangover and need to wear sunglasses to hide from the light, but that’s nothing compared to the headache. I stared at the ground and everything shimmered. Here’s the shot I took when a migraine started:

I like it as an abstract shot. I also think it’s a fair representation of my visual field when a migraine starts. When I got home, I realized that I’ve had a number of migraines this spring and summer while using a camera. Scrolling through my archive, I found the photos I shot each time a migraine started. That’s when I noted a pattern.

The last time I got a migraine, I was stalking a seagull along a beach south of Ayr. The sand was wet and reflective. Viewed from a low angle, it had a plastic quality, transitioning seamlessly into the bay beyond, and the distant hills of Arran and the clouds above. It all began to shimmer. Again, a squirt of Imitrex. I packed up my gear and walked away. Earlier in the spring I was hiking along a trail that leads to the shoulder of the Sleeping Giant north of Superior. A stream tumbled down the rocks beside the trail and every now and again I paused for a shot. At one point, I stared up the slope at the water splashing towards me, the afternoon sun glancing off water, and something disappeared. I walked a little further, flirting with denial, but when the aura started in earnest, I had to stop and announce that it was time to turn around.

From this, I surmise that bright sunlight reflected from below acts as a trigger. Unfortunately, bright sunlight reflected from below also produces interesting photographs. Since I’m not about to stop trying to shoot interesting photographs, there’s nothing for it but to put up with migraines. Maybe I should leverage the situation to sell myself as a suffering artist. Maybe I should cut off my ear and shoot starry nights and flocks of birds swarming around my head.