It’s time to take Rebel down for her late-morning pee in the grassy patch on the corner. I’m the last person I would’ve pegged as a slave to a dog, yet here I am, making baby talk to a black furry creature, clipping the lead to her collar, following her down the hall to the bank of elevators. She’s a standard poodle, the runt of the litter, so I’ve taken to calling her a substandard. If she was full-sized, I expect there’d be trouble from the property manager or the condo board since, officially, the by-laws put a limit on the size and weight of our pets. I keep the dog’s grooming on the far side of unkempt. That way, if any of my more fascist neighbours mentions the by-laws, I can say it’s all hair; underneath, she’s a little rat of a dog. Although a handful of my neighbours are anal beyond telling, I doubt any of them cruises the halls with a scale at the ready. Rebel wouldn’t stand for it.

At street level, we veer right and on past the office building. Taken together, our condo and the office building present a withering concrete face to the drivers whizzing along the arterial city street. If Brutalism wasn’t recognized for its soul-crushing effects before our building appeared on the scene, it certainly was the instant they cut the ribbon. But the late spring sun shines on its face and stokes the concrete, and its radiant warmth fills us with an ironic sense of well-being. Rebel tugs at the lead and I stumble along behind, trying to keep up. She wants to sniff at each light standard in front of the office building, read whatever messages her male friends have left behind, but at each one I yank her away to keep her from prancing through the bird shit that circles each of the standards. Substandards. I’m sure if viewed from high above, viewed from the perspective Google Maps gives us, everything in my world would appear orderly, but viewed from the ground, everything assumes a rough granularity. Dog piss streaming in rivulets through plops of guano. Vomit running down the side of a concrete planter. Rat traps wedged into shaded recesses.

At the corner is a stoplight and, beyond it, our road passes over a bridge that spans the road underneath. In the stoplight pantheon, this one is a lesser being: it only controls access to the on-ramp that descends to the road underneath. The road underneath proceeds across another bridge that spans a ravine road far below. Bridges over bridges. Roads over roads over roads. M. C. Escher starting from a nightmare. A grassy stretch follows the on-ramp down to the road underneath. This is Rebel’s pee patch. She can never just squat and go. The ground is rich with the scents of other condo dogs. She sniffs back and forth, back and forth, working to a spot that satisfies some incomprehensible need, then settles on her haunches and releases a morning’s accumulation. I’ve learned the hard way that I need to stand uphill from Rebel when that moment of release arrives. Especially when I’m in my sandals.

As Rebel attends to her bladder, I do her the courtesy of looking away. I do it thanks to my conservative middle-class upbringing, even though I’m certain Rebel has no concern that I might be violating her personal privacy. She’s remarkably free about when and where she urinates or shits or licks her genitals. I, on the other hand, am overly fastidious when it comes to matters of elimination and personal grooming and would need years of psychotherapy if my neighbours caught me squatting naked over this grassy patch. Do unto others, I suppose, even if those others happen to be canine. So I look up the on-ramp to the stoplight and I whistle, then I turn the other way and look down the on-ramp to the beginnings of the bridge that spans the ravine below and, again, I whistle, waiting for that blessed moment when the spigot runs dry.

Cars ease past me down the ramp and wait at the bottom to merge with traffic crossing the bridge below. Meanwhile, cars rush past and cross the bridge overhead. All this rubber on asphalt coalesces into a general thrum that could be the engine of a vast machine. If I immerse myself long enough in the sound, it fades from consciousness. That fading has a name, I’m sure of it. It’s the auditory equivalent of nose blindness. Sometimes Rebel will leave something horrifying on the kitchen floor and, even though at first I’m overwhelmed by the stench, as I gather the shit or vomit into the folds of a paper towel, it loses its pungent edge. Only by stepping out of my unit and then stepping back inside can I recover the immediacy of the revulsion I felt when Rebel first heaved her gift onto the floor. Something similar happens to the roar of the traffic. Within a minute or so of stepping onto the sidewalk, I become inured to it.

A man rounds the corner, past the pole that supports our lesser stoplight, and ambles down the on-ramp. He pushes a bicycle, peculiar for the fact that it’s a “girl’s” bicycle meaning it has a step-through frame and peculiar, too, for the milk crate fastened with bungee cords to the rack behind the seat. The man stands full in the morning light, assaulting my eyes with a messianic glare that forces me to look away. There’s little I note about the man except the obvious. He’s thin. He has a shock of wavy straw coloured hair. And he’s probably homeless because everything about him is crusted in a layer of dirt, his hair, his unshaven face, his ratty clothes. He pushes the bicycle past me to the foot of the on-ramp where he leans it against a tree then disappears down a dirt path that goes beneath the bridge. There’s an encampment underneath the bridge where homeless men live rough, and more encampments further down the slope into the ravine, tents scattered here and there, bits of bright-coloured nylon visible when breezes rustle through the valley and unsettle the brush. I wouldn’t know anything about the encampments except officious residents in my building have complained at the Board’s AGM: some evenings, when they sit on their balconies and swill their hot toddies, they catch glimpses of a tent through the leaves; one even saw a naked man. Oh my!

Prompted by their complaints, I’ve tramped through the woods that slope behind our building to see with my own eyes what’s got my busy-bodied neighbours so riled. Naturally, I bring a camera with me to document what I see. Wouldn’t be much of a photographer if I didn’t bring a camera with me. So, yes, there are tents. There are blue latex tourniquets. And, given all the spent needles, I wouldn’t take Rebel for a walk in those woods. I suppose there’s something to my neighbour’s complaints. On the other hand, if you elect politicians who, in the name of cleaning up the city, close all the safe injection sites, then you have to expect that the addicts will go somewhere. They don’t magically sprout up from the forest floor like mushrooms; they end up there because that’s the corner we’ve backed them into. That at least is my view of things, but I never get to share it with my neighbours and they never ask.

I find it hard to get myself twisted into knots over such things. As someone once said, the poor are always with us, and if that was true two thousand years ago and is no less true today, then the problem of poverty is intractable enough that I’m not about to solve it either. So, when Rebel has given up her last drops, I urge her away from the grass and onto the sidewalk, and together we climb back up the on-ramp. We leave the ravine behind and ride the elevator to our terrace where we survey the city from high above and take pleasure in the orderly way it unfurls beneath our feet.

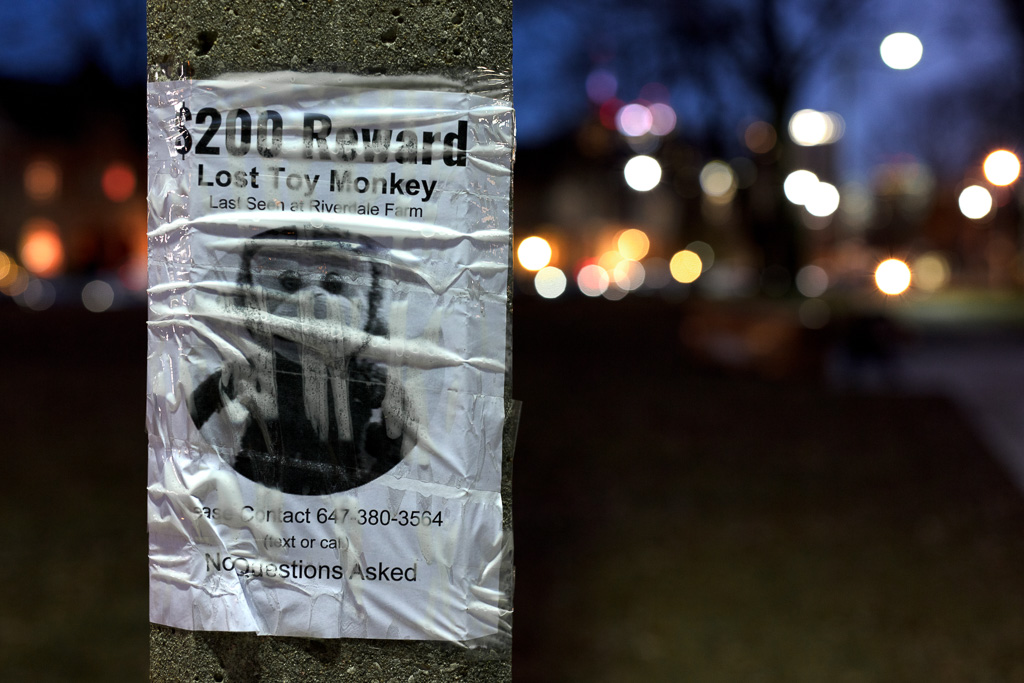

The next time I take Rebel down, later that afternoon, I note that someone has stuck a letter-sized sheet of paper to the stoplight pole, tape going around and around and around so that not a single bit of the paper is exposed to the elements. Approaching the pole, I see that the piece of paper is a notice, a plea for help really. Someone has lost a sister/mother/wife. There’s a description. A place downtown where she was last seen. A phone number. Please call. I see these notices taped to poles all the time. People gone missing. Lost dogs. Rare tropical birds. Once, a toy monkey and a $200 reward. Some monkey! I wonder if these notices work. I suppose they do in the sense that they make people who post them feel useful, they give the bereft a feeling of hope.

How do people get lost? There is the lost of losing one’s self, a spiritual or psychological disappearance that might best be understood as a self-effacement or a merging of the self with a wider reality. Sometimes I experience such a feeling when I take an afternoon to wander with my camera along city streets. Through pure observation, I remove myself from the scene. I pretend I’m invisible, a ghost haunting the living city. I feel it, too, when I lie on my back and stare into the night sky with its thousand stars shining their light to me, sometimes from a past so long ago that humans had not yet learned to walk upright when the light began its journey. But there is this other lost, the lost of physical separation from family and friends. I see evidence of it wherever I walk, on utility poles and public notice boards. We love you. Please call. Our worry is tearing us to pieces. I don’t understand the mechanics of this physical lostness. What can we say for our world that it allows someone we love to go missing in it?

This time, I have brought my camera so, when Rebel is done peeing on her patch of grass, I lead her down to the foot of the on-ramp where the bicycle still rests against the tree. I stare down the dark path that leads underneath the bridge but see no one. Anticipating the shot, I had already fixed the camera settings before I left my condo: 400 ISO, a basic aperture—f/5.6, and a reasonably fast shutter speed given that it’s a bright afternoon—1/1000. I’m shooting with a 50mm lens, nifty fifty is what they call it, they, the conventional rabble, the rule-bound shooters clamouring at me from their cages. I drop to my knees and frame a shot, but only get off a couple exposures. There are other people milling around with their dogs and they make me feel self-conscious. I wander with my camera for hours at a time through city streets without giving a care for what people think of me, yet here, almost on my own doorstep, I feel like an insecure teenager.

I know the image isn’t great. It’s blown in the top—a bright washed-out sky. It looks more like I shot it in a California desert than on the crest of a Toronto ravine. Afterwards, working in post, there’s little I like about the image. I’ve gone at least one stop over, which means that even though I shot in RAW, there isn’t any colour information in the highlights for me to recover. It’s a shitty photo. I hate when I make a shitty photo. I hate what I do to myself inside my own head when I make a shitty photo, the self-castigation, the self-flagellation. If I was a monk, bad photography would be my sin and I would have to atone for it by walking 20 kilometres carrying 15 kgs of gear including a 400mm lens and a tripod until my back bowed beneath the weight and I cried out to the gods of photography: forgive me my sins and bless me with a few good shots! Another time, maybe. For now, I go to the fridge and pull out a beer and settle again in front of my 5K screen and contemplate what creative tricks I might use to salvage this image of a discarded bicycle. Rebel watches me from the floor, then turns away disinterested and licks the fur on the inside of her thigh.

Once a week, Rebel and I go for an extended walk, 8 or 10 kilometres through the ravines or down to the Lower Don Trail. We can’t do this more than once a week because neither one of us is young anymore and too many of these walks would wear us out. I hoist a pack loaded less with camera gear than with water bottles and a collapsible drinking bowl, then we meander with no fixed goal. Maybe we wander down Rosedale Valley Road, or through Cabbagetown past the Necropolis and the farm and down into Riverdale Park, or down Milkman’s Lane and along the Beltline Trail to the Brick Works. On our weekly walk, we pass community notice boards, concrete utility poles, coffee shop bulletin boards, all of them plastered with notices: Have you seen Hanna? Variations on the poster we first saw near Rebel’s pee patch. Now, they offer the additional information that when she was last seen she was riding a bicycle, torn seat repaired with duct tape, and a green milk crate fastened above the rear wheel. The posters have spread like toadstools after a spring rainfall.

I pause in front of the Riverdale Park notice board and stare into Hanna’s eyes. Are they soulful? Are they troubled? It’s difficult to say. I know these kinds of photos—shot on an old model iPhone, relatively low res, algorithmically enhanced, blown up beyond their native resolution on a laser jet printer at the local Staples. Leave the posters to fade in the sunlight and soon it’s hard to know what the eyes might once have held. I’d like to believe I could read those eyes and relate a story complete in itself, but years of wielding a camera, pointing it into people’s eyes and promising that I’ll magically capture their essence, has turned me into a photo apostate. I’ve lost the faith. I’m like the priest who proclaims from the pulpit that the black book is just a collection of words. These images we hold so dear are arrangements of ones and zeros; there’s something demeaning in the suggestion that ones and zeros can tell us something of the spirit. I see how the trick is done and can no longer recover my sense of wonder.

After our walk, I leave Rebel to snooze on her bed, half in, half out, hind legs splayed across the hardwood floor, and I step onto the terrace with a cold beer and I gaze over the green canopy that flies up to the north. Two fire trucks sit in the valley far below, engines idling and lights flashing. There’s nothing unusual about fire trucks and flashing lights, not in the city. There’s a fire station cornerwise from our building and it answers calls every twenty minutes or so. The sirens are so frequent they’ve ceased to impinge upon my consciousness. I’ve become one of those horrible people I used to complain about, the ones who refuse to change their pace crossing the road as the fire engine bears down on them. It’s not that we refuse to change our pace; it’s that we’ve ceased to acknowledge the existence of fire engines. They’re all sound and fury signifying nothing. Looking down to my left, I see how two police cars sit on the bridge that spans the valley, lights flashing in answer to the fire trucks underneath them. Two ant-sized police officers are leaning over the railing and calling down to people beneath them who are hidden from my view by the treetops. They wave then tie yellow tape to the railing and, unfurling their roll, walk it back to the foot of the bridge.

On the evening news, the announcer reports the discovery of a body in the dense brush alongside Rosedale Valley Road. Police haven’t identified the body yet, but I expect it’s Hanna. I think of her inscrutable eyes staring at me from the notice board. It’s dark when I take Rebel down for her evening pee. Darkness gives the flashing lights a sense of drama they don’t deserve. Maybe the lights induce a tiny squirt of adrenaline with its heightened sense of awareness, as if to signal that this is really real, a confirmation that I’m alive even as the lights declare the scene of a death. The police have put down stakes, drawing yellow tape beyond the end of the bridge, past the bicycle, cordoning off the lower third of Rebel’s pee patch. A police officer stands on the grass and nods when I motion that I intend to set Rebel loose on the higher ground.

I sat chilled and stinking and anxious and repeated it to myself like a mantra: Fuck the police. Fuck the police. Fuck the police.

I treat police officers the way I treat bumble bees: I leave them alone and hope they leave me alone, too. My parents raised me to believe in a Mayberry view of policing where even-tempered folks draw on limitless funds of common sense and goodwill to keep the peace. But my years pounding the pavement with a camera have wrung the down-home lifeblood from my childhood view of things. I’ve seen for myself how they card Black kids for nothing more than shooting hoops on the Esplanade, how they run homeless men out of the city parks, pants around their ankles and bags spilled into the road. It was the cruelty that accompanied their actions, the twist of the mouth, the taunts, that started me questioning my assumptions about policing.

What settled my view forever was the G20 summit in 2010 when nearly 20,000 police officers turned downtown Toronto into a military stronghold. I was utterly preoccupied with trying to get a shot at Queen and Spadina, oblivious to the troops gathering at various points around the intersection, until it was too late. In all their riot gear, they fell into place behind me and that was that: I was kettled. Their interlocked shields formed a solid wall around 200, maybe more, kids with skateboards, seniors carrying bags of groceries, mothers pushing strollers, journalists, protesters carrying signs, teenage sweethearts out to see what was happening, shopkeepers who had stepped outside to take a look, and me, the fool who was mesmerized by the reflection of darkening clouds in police visors. The sky had turned black and I remembered Mr. Paterson, my high school English teacher, the one who taught Lear and went on about pathetic fallacy, and I wondered if there wasn’t something to the idea that the elements tremble in sympathy with our sorry concerns. The wind had picked up and blew our words back into our faces. Oh we yelled! But it did no good. The sky yelled louder. Big drops splashed on the asphalt and mixed the oil and dust into a greasy paste. For an instant, you could smell it, and then the sky opened up in what Mr. Paterson might have called a cataract. The police were stubborn bastards and refused to move despite the rain, so we were soaked through, shirts stuck to our skin, and my camera destroyed, the electronics of my first good DSLR completely fried. The next morning, after I was released from custody, I went home and tried to retrieve images from my memory cards, but even they were ruined. Water had gotten into everything. I could have thrown my gear into the shower and done less damage.

Reviewing my notes (my notebook had been reduced to pulp but I reconstructed my notes from memory during the week that followed the incident), I see that the destruction of my camera infuriated me less than the fact that I pissed my pants while I stood in that cinching square of police. Even before the kettling began, I had noted to myself that my bladder was full and I should keep an eye open for a chance to relieve myself. After three hours standing in the rain, I was hopping from foot to foot and the damp clothes only made things worse. For the first and only time since I was weaned from diapers, I emptied my bladder into my pants. It was dark and everything was already soaked, so no one knew what I had done and I suffered no public humiliation as a result. But I knew what I had done. And afterwards, when the police had carted us to the makeshift cells on Eastern Avenue, and we were sitting 15 or 20 to a cage, I could smell a hint of urine wafting up from the soles of my feet which were already redolent with an odour all their own. I worried that someone else in my cage might have a super nose, might be a certified urine sommelier who could identify the source of the odour and surmise from that fact alone what had happened. I sat chilled and stinking and anxious and repeated it to myself like a mantra: Fuck the police. Fuck the police. Fuck the police.

Rebel finishes her work and I sidestep the resulting puddle, hoping it doesn’t all soak into the ground before at least some of it dribbles down to the police officer standing by the yellow tape. I turn to leave and stare at the stoplight, the lesser stoplight, the one that regulates traffic to the on-ramp. I’m standing in more or less the same position as when the homeless man pushed the bicycle down the sidewalk and left it leaning against the tree. I turn back to the police officer and look to the trees beyond him. The bicycle still stands where the homeless man left it, now circled by its own strip of yellow tape. I take a step towards the police officer, thinking I should be a good citizen and say something. But I pause. I have doubts. I doubt my powers of observation. I doubt my powers of recall. I didn’t get a good look at the man. The early morning light, all glare and no definition. Light diffused around a wild shock of hair. Thin shoulders. Ratty sweater. Possibly grey. Possibly beige. Who’s to say? If all I have to offer by way of clues are these pathetic slivers that pass for a recollection, I know well enough what will happen: I’ll become a suspect in their investigation and suffer years of grief. Don’t get involved, I tell myself. Don’t draw this down on your head. Remember: they’re bumble bees.

I turn again to the lesser stoplight and tug at the leash. Together, Rebel and I return to our building and ride the elevator to our concrete box in the sky. I stay up for the evening news and the announcer provides an update on the grisly discovery in a Toronto ravine. The words never change. A body is always a “grisly discovery.” A local resident was out walking his dog when he made a grisly discovery in dense underbrush beside the road. Although the body was too decomposed for immediate identification, it is believed to be the body of a woman reported missing nearly two weeks earlier. Police are calling on anyone with information that might help in the investigation to contact them … and the usual phone number scrolling across the bottom of the screen. The announcer’s patter is accompanied by the obligatory shots: close-up of yellow tape, shallow depth of field to blur the blue and red lights flashing in the distance, medium shot of a police officer walking the perimeter of what (so far) they have refused to confirm is a crime scene, long shot from the bridge: road stretching below and disappearing into the trees.

I leave Rebel to snooze on the floor and step onto the terrace to catch a final whiff of the cool night air. After a winter of long dark nights confined indoors, it’s a relief to have the warmer weather and I’m determined to enjoy as much of it as I can. I settle into a cushioned lounge chair, tilting my head and staring into the night sky. Wisps of cloud drift past, bearing an orange tinge, as if they’ve slipped into our atmosphere from another dimension. They used to be tinged a cool blue/white until the city fitted all the streetlights with more energy efficient bulbs. I doze to the sound of idling engines and official voices calling to one another.

Moira visits me in my sleep. God I miss her. I remember how frantic she was the night the police arrested me and shipped me off to the detention centre on Eastern Avenue. She had no idea where I was until I phoned the next morning, and she drove down to pick me up, me, twice as old as anyone else waiting on the curb, she, like one of the parents, scolding me for being an idiot, then turning into a wife and kissing me in spite of my idiocy. And there she is in my sleep with a finger pressed to her lips. What does it mean? This finger to her lips? She lingers in the shadows, so the smile, the eyes, all the customary signals lie shrouded.

Moira is my missing person. It’s a strange thing to say, given that I know exactly where she went, first to the hospice where she drifted in and out of consciousness, then to the funeral home where the mortician made cursory preparations before the cremation, and from there to a box which I drove to our agreed-upon sites—memory-soaked sites—to scatter the ashes, but to me she is still a missing person. I have no idea where she went. With an ache in my chest, I want her back. There are times when I think it might do me good to make up a poster, take the file to Staples, and print up a hundred copies. Missing: Have you seen this woman? Tape it to a hundred different poles. I have a 24 Tb RAID storage drive and on it I keep hundreds, maybe thousands, of beautiful portraits I’ve made through the years. Any one of them would do nicely on a poster. And yet not one of them is a portrait of my Moira. Have you seen this woman? (Bearing in mind that this woman is not a woman; only a representation of a woman; ones and zeros; digital instructions to a cheap laser jet printer; a dirty trick we play on ourselves to persuade ourselves we once had a life with this person.) Christ, I need to stop talking to myself like this. Maybe that explains the finger to the lips.