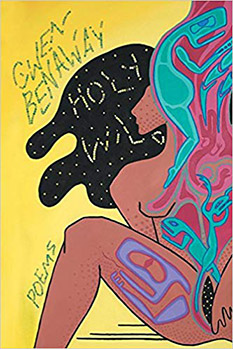

Last Tuesday, we learned that Gwen Benaway has won the Governor General’s award for poetry for her third collection, Holy Wild. The announcement arrived just in time to stand as a great fuck-you to the hate-mongering facilitated by the Toronto Public Library which had rented a room that evening to an outspoken TERF named Meghan Murphy who thinks trans people aren’t real. You see, Gwen Benaway is an Indigenous trans poet and writes mightily to make the experience of a trans woman as real to others as possible.

Even a cursory reading of Holy Wild assaults our senses with a relentless documentation of the many ways a trans woman is despised for who she is. Cries of pain at the violence visited upon her. Lamentations at the betrayals. But also hope. Hope for a new life through a new body and through new relationships that promise understanding. But more than these, a gathering strength to assert herself as her, whether or not these hopes are realized.

I have no idea if it was intentional, but in form and tone, the entire volume resonates with traces of the Book of Psalms, another great cry issuing from the lips of a despised and suffering people exiled from their native land.

Poetry is the language of solidarity. It is the home of metaphor, the radical leap into another’s experience, the bridge between different ways of being. The radical identification that solidarity demands is only possible by fostering poetry (either writing or reading, preferably both). The language of rational prose engenders separation and alienation, from the self, from the land. The rise of rational prose (and its attendant literalisms) in the contemporary world, and the corresponding denigration of poetry matches the rise of a strident public discourse that infects social media, the rise of a hateful radicalism—on both left and right—that refuses meaningful engagement, and the reduction of spiritual practice to masturbation in front of a mirror. Poetry can’t promise redemption; it can’t even promise consolation. What it can promise is the soulful assurance that we are not alone.

At roughly the centre of Holy Wild is a poem called “Phoenix” whose two pages stand as a useful illustration of things that happen in the whole volume. If Benaway were a musician (and maybe she is; I don’t know) then she’d be plucking three strings on a lyre. One string is the land. In “Phoenix”, we hear this only briefly: “someday I will forgive you in a forest” and “someday you will forgive me under a mountain”. But the land is important throughout the collection, as signaled by the fact that it opens with a poem called “Akii”, an Anishinaabemowin word for the land or earth:

ohmamaaminaan

mother of us all

give me the land,

call us by our name

The second string is her body. “Phoenix” is a tactile poem: “Graft new skin to the raised edges…” Bodies, touching, scars, palms, calluses. Our bodies come from the land and, ultimately, return to the land.

The third string is the poem itself which, metaphorically, is an embodiment. This is more obvious in “Phoenix” than in other poems because it is presented as alternating left and right justified lines: two different bodies in one poem.

Together, the three strings—land, body, poem—reverberate. In fact, another of the poems in the collection is called “Reverberation”. The strings don’t often reverberate in harmony. But what were you expecting when the body is so often assaulted, raped, despised, reviled, rejected? Harmony is something to be hoped for, but it belongs somewhere beyond these pages.

“Phoenix” opens with a brief statement:

this is a trans poem. it is two poems in one body but truth lives in the centre. it does not need surgery to fix it. its preferred pronoun is a multitude. it wants to be fucked but sometimes it wants to fuck you.

Then follows the ironic opening line of the poem proper: “I am tired of explaining the fire.” Yet she feels she must go on explaining it, as if she has no confidence in her poem/body to stand in its own right, and to be understood on its own terms.

Ordinarily, I would say an explanation is unnecessary; a poet must learn to trust, and to surrender some responsibility to the reader/listener. But in this context, explanation is part of the poem’s meaning; it would be incomplete without it.

Even so, I can’t help but wonder what Benaway’s poems will be like in years to come when, presumably, she feels more at ease in her new poem/body. Perhaps she will be able to dispense with explanation and trust that she is understood.