On Sunday, we went to West Hill United Church which holds itself out as a “progressive community of faith.” See an earlier rant for more on the reaction provoked by its minister, Gretta Vosper. I’ve never been to a “progressive” service, and so I didn’t know what to expect. Maybe most of the members would be leftovers from the sixties, diffuse potheads smiling amiably when we walked through the door; or maybe we would find a cult of personality, utterly devoted to its spiritual leaders; or maybe the congregants would be a cerebral bunch (given that their web site calls for an approach which is “intellectually rigorous”); or maybe they would be a charismatic crowd, inspired by a fresh view of things, falling down on the floor as they whacked one another on the head.

To my shock (and perhaps to my disappointment), the service unfolded in precisely the manner that I would expect of any other United Church congregation in Canada. There were subtle differences. For example, the “announcements” page welcomed visitors and church shoppers. But in its broad sweep, in its structure and tone, the rituals of the service were identical to those of the church I have lately abandoned. I had thought that if, as they claim, faith is a “human construction” (whatever that means), then a religious service would be all the more a human construction, reflecting the idiosyncrasies of its community in all its particularity.

Instead, I found myself singing familiar hymns, listening to a reading from the lectionary, enjoying a sound — indeed, an excellent — homily delivered by a member of the choir (the minister must have been on vacation). As I had expected, there was no confessional prayer, but I was alarmed to find myself reciting the Lord’s Prayer, and in Elizabethan English too: “Our Father, who art in heaven, hallow’d be thy name …. ” God as father? Living up in heaven? Doesn’t sound terribly progressive to me. What’s going on here? I asked myself. In search of an answer, I turned to the prophet of the progressive movement—John Shelby Spong. Not coincidentally, West Hill United Church shares its address with the Canadian Centre for Progressive Christianity, and likewise not coincidentally, when the CCPC had its launch, Spong was there to offer his blessing.

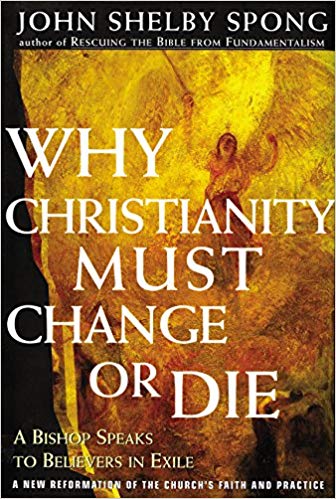

In his book, Why Christianity Must Change or Die, Spong provides what almost passes for an apology (in the formal sense) for the claims of progressive Christianity—discarding tired imagery and replacing it with new proposals, challenging doctrine much as Luther did 500 years ago, hinting at a shift from faith to ethics. When I first read this book, I had the overwhelming sense that Isaac Newton was lurking in the wings, with his humble deference to those who had gone before him: “I stood on the shoulders of giants.” In the same way, Spong stands on the shoulders of Newton. He tries to account for the religious impulse in an age of mathematics and logic and scientific method, where the old texts no longer bear rational scrutiny. Spong may be a prophet, but in one sense only. He is not an exegete, revealing hidden meanings in the text; nor is he a sphinx, guarding our access to the text; nor is he a a Cassandra, warning us of the inevitable consequences of our profligate readings of the text; instead, he is a translator, reorienting our old words to a new language. Now, we speak the language of Isaac Newton, the language of empiricism and natural laws.

But Spong’s book contains an anomaly. When he wrote the book (published in 1998), he was still a bishop of the Episcopalian Church in the U.S., and so he had to reconcile his skepticisms to his office—an office which demanded that he perform rituals such as baptism (to wash away sins he no longer acknowledged) and prayer (to communicate in a way that no longer made sense). Spong’s anomaly is this: he continued to practice rituals and felt justified in so doing, even though he had discarded their meanings.

I am not so sure that Spong is justified. If I do not believe that god is a father, how can I pray “Our father … ” ? Can I claim with integrity that the forms are of no consequence? Can I assert myself as faithful if I am unfaithful to myself? Even if a form is without content (praying the words, for example, while ignoring their import), does the form itself not import meanings which undermine my professions?

It seems to me that form and content must align themselves, perhaps not immediately, but inevitably—otherwise the most one can say of oneself is: I am a hypocrite.

But I pose my questions gingerly. I don’t have all the facts and, like a good Newtonian, I need all the facts. I will return to West Hill United and press for answers to my questions. I don’t expect an immediate answer. I am patient. I have exactly as much time as I need.