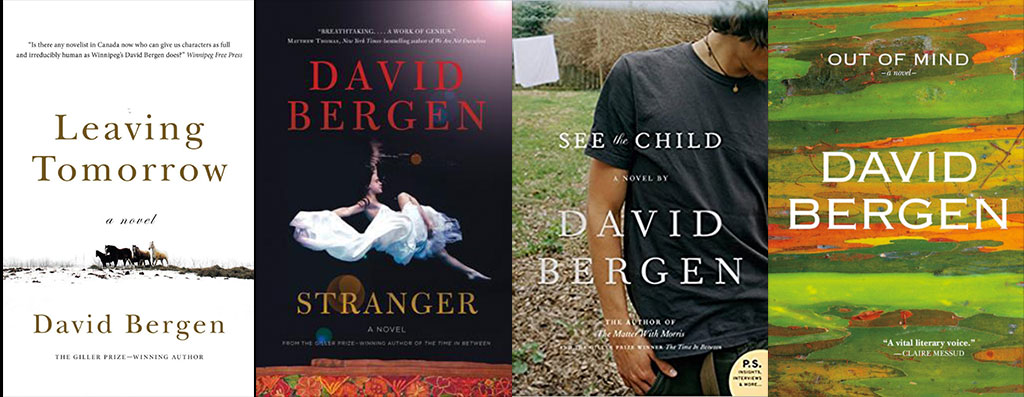

See The Child, by David Bergen (Toronto: HarperCollins, 1999)

Art and life are porous frames that bleed into one another. David Bergen’s early novel, See The Child, opens with a knock on the door. Harry, the local police officer announces to Paul Unger that they have found his teenaged son face down in a farmer’s field, apparently drowned. I finish a few more pages, then set the book down on my night stand and go to sleep. Shortly after four in the morning, I wake and pad to the kitchen for a glass of water. On the way, I pass the door to my son’s room and note that I didn’t hear him come home. Throughout the pandemic, he has been remarkably compliant and has been great company in lockdown, but as things relax, the tension is palpable. He’s itching to get back to his old routine: going out with girls, seeing friends IRL, wing nights, pubs, blowing off steam. On the way back to bed, I poke my head in his room and see that his bed is empty. I shrug and crawl back into bed but I can’t sleep. David Bergen’s novel has infected my brain with that most horrible of parental images: the child who dies. My catastrophizing brain can’t get the image out of my head—especially the bit about discovering the boy’s body surrounded by a murder of crows—and I can’t help but extrapolate to my own situation. What if? Just text him, my wife suggests. Writing in 1999, not even a generation ago, Bergen’s characters didn’t have texting or cell phones or any of that; once a child went out, they were out, and communication happened by chance.

Although Stephen’s death has only a slight place in the novel, it provides the impetus for all that follows. As often happens with couples who lose a child, Paul and Lise split, and although people around them—especially Paul’s mother—hope for a reconciliation, it never happens. Paul owns a furniture store in town, but he surrenders responsibility for it to other people and retreats to a rural property where he keeps bees. When he learns that Stephen got a girl pregnant and that he is now a grandfather, he opens his home to Nicole and Sky. Nicole is not what one would describe as the most stable individual ever to walk the earth, given her tendency to switch partners the way some people switch shoes, her inability to stick to a task, whether that task relates to Paul’s beekeeping or to any other job she undertakes, and the general disorganization that plagues her existence.

Since this is rural Manitoba, people talk and their talk is unkind: the only reason Paul is keeping Nicole out at his house is that he must be fucking her. Imagine! Him and his own son’s girlfriend! Paul believes his motivations are more high-minded than that: he wants to inject some measure of stability into his grandson’s life. Nevertheless, his relationship with Nicole is fraught with sexual tension and, as the novel progresses, he begins to suspect that what he feels for Nicole is love.

See The Child falls squarely within the commercial realist fold, and David Bergen is one of its great stylists. It is plot driven, with tension and resolution. It is rooted in the real world, and while readers may not be familiar with Manitoba, if they felt so inclined, they could fly to Winnipeg and get a feel for the world that is the raw stuff of Bergen’s novel. He isn’t writing about prairie fields in the abstract, but about this field, swept by this dust, with this gritty taste on the tongue. This approach does a couple things for him, one of which strikes me as problematic, the other of which strikes me as wonderful.

The first is this: the emphasis on plot which drives novels like this paints Bergen into a corner. He has Paul Unger chase Nicole and Sky into rural Montana. Fair enough. Paul wants to retrieve the child because he knows Nicole is hellbent on some idiotic plan without regard for the child’s needs. However, she is living with a lumberjack twice the size of Paul who is disinclined to give Paul any play in their nice little domestic arrangement. Paul answers the situation by purchasing an illegal gun and, as anyone who has read Chekhov knows, if you introduce a gun into a story, then you risk turning it into a ridiculous story. The upshot of this exchange is that Paul finds himself stranded in the middle of a remote field during a blizzard, at risk of hypothermia and frostbite. The Neanderthal lumberjack has taken back his woman and her child and god help Paul if he ever tries to do anything about it. This episode would have done well in a Coen brothers movie. Unfortunately, Bergen wrote it straight and it falls flat. It reminds me of the situation where somebody recites the lines of joke, unaware that the lines come from a joke, and so his delivery falls flat because he doesn’t know where the proper inflections go.

At the same time, Bergen’s approach produces something wonderful. He resists the temptation to draw his novel to a neat resolution, gift-wrapped, with a red bow. Instead, everything remains indeterminate. Nicole has run off with Sky, maybe to Las Vegas. But who’s to say? As the grandson’s name suggests, the future is wide open. Meanwhile, Paul has returned to his beekeeping, with perhaps a twinge of unrequited love for Nicole, and a deep ache for his dead son.

More than 20 years after this book was published, I lie awake in the darkness and my iPhone dings. An hour after I sent my message, my son notices and responds: “Yeah, I’m staying out tonight. See you later in the morning.” I pretend I wasn’t worried. I roll over and try to catch another hour of sleep before the new day begins.