Three more days until the Oscars and four more Best Pictures nominees to get through in my “Dissing the Oscars” series. If I’m going to look at them all before the winner is announced on Sunday, I’ll have to double up my reviews. So why not lump together the “quirky” films from the “quirky” directors? I’m referring of course to Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds and Joel and Ethan Coen’s A Serious Man. Tarantino and the Coen brothers have much in common quite apart from quirkiness:

- they like their comedy dark;

- they aren’t afraid to make stark juxtapositions of light and heavy themes;

- they both have elicited hammy over-the-top performances from Brad Pitt (see Burn After Reading);

- this year both address Jewish concerns;

- both structure their films with chapter headings

- critical response tends to be more polarized than with other film makers; either you like them or your don’t; there’s no middle ground.

I have to confess that I like the films of both Tarantino and the Coen brothers. I like their sensibilities. I like their ability to make good fun out of the absurd.

Inglorious Basterds

With Inglorious Basterds, we have a Jewish revenge fantasy in which three different groups converge on a Paris Cinema during World War II and torch the place, but not before pumping Hitler, Goering, Goebbels and Bormann full of lead. The Inglorious Basterds is a crack unit of Jewish American soldiers whose mission is to wreak havoc throughout occupied France and to deliver 100 Nazi scalps each to their commanding officer, Lt. Aldo Raine (Brad Pitt), who is known as The Apache. They become the contact for a British spy, Lt. Archie Hicox (Michael Fassbender), posing as a German film critic. The meeting has been facilitated by German starlet, Bridget von Hammersmark (Diane Kruger), who has secured tickets for the premiere of Goebbels’ latest propaganda masterpiece, “Nation’s Pride.” The cinema is owned by Shosanna Dreyfus (Mélanie Laurent) who, unaware of the assassination plot descending upon her venue, hatches a plot of her own. We saw a younger Shosanna at the outset of the film fleeing from Col. Hans Landa (Christoph Waltz) who had slain Shosanna’s family. As The Jew Hunter, Waltz’s portrayal of efficient bureaucratic evil is among the most satisfying performances of the year and I expect it will garner him an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor.

Among the Basterd dissers is Michael Sragow of the Baltimore Sun who writes that it is “so hollow and protracted that it transforms mayhem into monotony.” Of course, this is the same critic who wrote about the “tingle of authenticity” he got from The Blind Side, so it’s hard to take him seriously. David Denby of The New Yorker says it “is not boring, but it’s ridiculous and appallingly insensitive.” Tarantino’s “virtuosity as a maker of images has been overwhelmed by his inanity as an idiot de la cinémathèque.” It seems a little pretentious resorting to French when all you really want to say is “Quentin, you’re an idiot.”

Both reviewers have difficulty with the fact that the film is about historical events that never happened. Somehow, it’s inappropriate to use a fictional backdrop for the telling of a fictional yarn. Apparently, it’s insulting or politically incorrect, or juvenile, or something — especially if that fictional backdrop too closely resembles troubling events in the real world. And yet, whether the reviewers have noticed or not, storytellers have been doing just that for as long as people have been telling stories. And it’s fair to suppose that writers and film makers will be using Nazis as stock villains for centuries to come. We’ve seen this in the Indiana Jones franchise and in The Boys From Brazil. While these assume the historical backdrop of Nazi Germany and the rise and ultimate fall of Hitler, other works imagine alternate histories. Notable among these latter works is Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, which assumes the defeat of the allied forces and imagines a world carved up between Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan. It could well be that the Book of Exodus is also such a work, imagining the toils of the Jewish people against the backdrop of a fictionalized Egypt and its despotic leader, Ramses II, but I leave that speculation to another post. I mention these blends of fiction and history merely to suggest that Srargow and Denby are being a bit supercilious in their concerns.

A Serious Man

A Serious Man tells the story of Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg), a Jewish physics professor who lives in a Minneapolis suburb. Set in the 1960’s, the “new freedoms” have become Gopnik’s nightmare. There’s the weed-smoking neighbour (Amy Landecker) who sunbathes nude in her back yard. There’s his son Danny (Aaron Wolff) who attends his own bar mitzvah stoned, listens to Jefferson airplane, and whines about how he can’t get “F Troop” because the TV aerial keeps needing adjustment. There’s the daughter (Jessica McManus) who steals money from his wallet because she’s saving for a nose job. There’s the wife (Sari Lennick) who wants him out of the house because she’s in love with Sy Abelman (Fred Melamed), a slimy passive-aggressive who quotes classic lines from Eric Berne’s Games People Play. There’s the helpless brother, Arthur (Richard Kind), who spends a good deal of his time locked in the bathroom draining a sebaceous cyst and working on a something he calls the Mentaculus which is probably the product of a psychosis. Add to this a Korean student who is trying to bribe him for better grades, a redneck neighbour who’s encroaching on his property line, a pesky collection agent from a record club, a real estate lawyer who drops dead during their interview, and anonymous allegations of moral turpitude delivered to the tenure committee. With all this chaos whirling around him, it isn’t surprising that Gopnik wants desperately to know what it all means. What is Hashem trying to tell him?

At this point, the parallels with the Book of Job become unmistakable. In his quest for answers, Gopnik meets with three rabbis who come off sounding a lot like Job’s faithless friends. The centerpiece of these meetings is the story of the goy’s teeth told by Rabbi Nachtner (George Wyner). A member of the congregation is a dentist who discovers Hebrew letters etched on the back of a patient’s teeth. The letters spell: “Help me.” He puzzles over the meaning of the message. Following the method of Kabbalah, he converts the letters to numbers. Maybe it’s a phone number. He dials the number and gets a grocery store. He goes to the grocery store but learns nothing. Gopnik asks what happens in the story; did the dentist ever learn the meaning of the message? Rabbi Nachtner doesn’t see the point of the question. The dentist goes on living his life. So what? We feel Gopnik’s frustration. Like him, we want answers and no one seems inclined to give them to us. Gopnik finishes by asking what happened to the goy. “The goy? Who cares?”

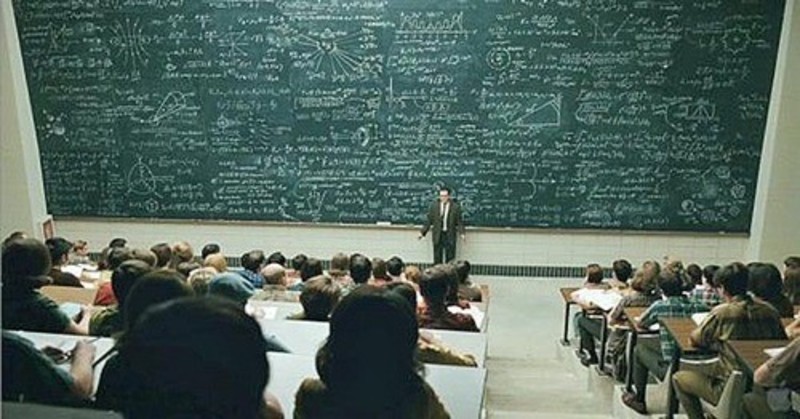

The movie is full of messages that prove either meaningless or impossible to interpret. We have Gopnik standing before a chalk board covered in mathematical equations — Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle — which “proves we can’t ever really know what’s going on. But even though you can’t figure anything out, you will be responsible for it on the mid-term.” The blur of figures on the chalkboard neatly echo the Hebrew characters on the chalkboard in his son’s class. We see similar figures again when the son is reading Torah at his bar mitzvah. Are the messages from Hashem any more certain than the messages from Heisenberg? There is Arthur’s Mentaculus: pages upon pages of numerical scribbles which he uses to win at an illegal game of poker. There is the TV aerial which picks up odd signals when twisted one way or another. There are dream sequences in which Gopnik imagines himself having sex with the neighbour and being shot by the rednecks. There is the coincidence of simultaneous auto accidents with its latent significance. And there is the final meeting with the third rabbi. This is the ancient Rabbi Marshak (Alan Mandell) who refuses to meet with Larry Gopnik but will meet his son Danny to congratulate him on his bar mitzvah. At the meeting, the venerable Rabbi Marshak quotes words of wisdom which are nothing more than lyrics from Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love”. What does it all mean? What is Hashem trying to tell us?

As a storm approaches, Gopnik receives a phone call from his doctor regarding the results from his x-rays. They need to talk. They need to talk in person. The film ends, just as indeterminate as Rabbi Nachter’s story of the goy’s teeth — or Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle for that matter.

A Serious Man wins the award as recipient of the harshest diss of any Oscar contender. That diss comes from Ella Taylor in The Village Voice and focuses on Jewish self-loathing and what she describes as its “Ugly Jew iconography.” This prompts her to call it a “loathsome movie.” The problem with her review is that she wasn’t paying attention when she watched the film. She says that all the Jewish people in the film are ugly, and excepts the nude sunbathing neighbour by reasoning that she is “probably a shiksa.” The problem is: in the movie I saw, the neighbour is Jewish, as the film makes clear on at least two separate occasions. Ella Taylor also complains about how Gopnik’s life gets better all by itself. However, the movie I saw implied that Gopnik’s life was about to get a whole lot worse. Taylor comes off sounding like she has a chip on her shoulder. It seems her vision was too clouded by anger to watch the film that was actually playing at the time. Too bad, because she missed an excellent film.

The Verdict

Both are eminently watchable films. Are they Oscar worthy? Apart from Christoph Waltz’s performance in Inglorious Basterds, I don’t think so, although A Serious Man comes close.