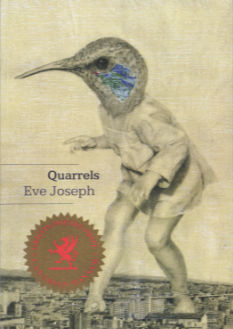

Quarrels, by Eve Joseph, is this year’s Griffin Poetry Prize winner. I’ve read the book, which is to say I’ve allowed my eyes to pass over the words, but I’m not sure the words have gotten past my eyes.

Quarrels is 66 prose poems, each of approximately 100-150 words. It is divided into three sections. The first section is the longest, 44 poems, and engages the reader in the wonder of illogic. For now, that is all I have to say about the first section. The third section is the shortest, 10 poems, and addresses death, probably the poet’s father’s death, given a comment in the acknowledgments. It is the middle section which is of greatest personal interest, 12 ekphrastic poems, each a riff on a photograph by Diane Arbus.

For me, these poems pose a puzzle about the relationship between photographs and written words. I accept Marshall McLuhan’s claim in The Gutenberg Galaxy that both are visual media. For some, this may seem counter-intuitive, especially as concerns written words, more so when those written words purport to be poetry. The usual assumption is that written words are merely encoded speech. Just as musical notations indicate how the music should sound when it is played on an instrument, so the words on a page indicate how the poem should sound when it is read aloud. In both cases, the performer grafts additional meanings that cannot be gleaned by looking at the notations. I don’t think McLuhan disputes this characterization of matters; however, he would point out that the leap from notation to performance engages us in two distinct media, each adhering to the terms of its own internal contract.

But what about photographs and written prose poems which, in the broadest sense, are both visual? On a naive reading of a photograph, we might say that it is representation: the subject of the photograph corresponds to something in the real world. The titles which Arbus assigns to her photographs suggest that this is precisely how we are to view them: “Five members of the Monster Fan Club, N.Y.C. 1961”, “Child with a toy hand grenade in Central Park, N.Y.C. 1962”, and so on. With these descriptions, why do we even need the photographs? Joseph uses the Arbus titles as the titles for her poems, raising the same question: with these descriptions, why do we even need the poems?

But we are not naive readers. We have learned Magritte’s lesson. His pipe is not a pipe. At most, it is a representation of a pipe. I have never seen Magritte’s representation of a pipe; I have only ever seen photographs of his representation of a pipe, which (following his own rules) is really a representation of a representation of a pipe. Soon, I am wandering through a hall of mirrors.

Despite the temptation to turn all of this into the intellectual equivalent of a fun-house complete with candy floss and carnival barker, we suspect that the Arbus photos are more than simple representations. Nearly 60 years after her wanders through Central Park, Arbus’s images continue to fascinate us. They fascinate us, not because they offer an accurate portrayal of a particular place at a particular instant in time, but because they suggest a sensibility, a way of seeing the world, maybe even a personal philosophy of life. She challenges our habit of slotting the people we encounter into the binary categories of normal and abnormal. We can’t assume the usual objective eye staring through the viewfinder. Instead, it’s a freak staring at freaks. Maybe freaks is too harsh a word even though it’s a word Arbus herself used to describe her subjects. In “Windblown headline on a dark pavement, N.Y.C. 1956”, Joseph hints at a gentler way of describing Arbus’s practice and, by extension, Joseph’s broadest poetic intention. She asks: “How do we talk to one another from the sanctuary of our own solitudes?”

In a way, it doesn’t matter what the medium, the message is the same. The medium’s inherent limitations underscore the fact that each of us encounters our world in the isolation of our freakish consciousness. Each of us yearns to take that isolation and crack it open, to share with others our ways of being in the world. This is what Joseph tries to do with her poems. This is what Arbus tried to do with her photographs. This is what each of us does whenever we open our mouths and engage the people we encounter in our daily lives.