Curves, the weight-loss people, have had an ad out for a while. I’m referring to the one called Hearts: “Curves works for your heart—and every other part of you.” The ad evinces a philosophy of health that serves the whole person. When Curves says it cares about your heart, it means something more than cardiovascular fitness; it seeks to promote an overarching sense of well-being. So far so good. Terrific! You get my thumbs up.

Except there’s one little thing that bugs me about the ad. Having a big heart means a generosity of spirit. A woman returns the man’s lost wallet. Another woman gives up her seat for an elderly bus rider. “Hearts that give a little,” the narrator says. “And a little more.” Cut to women grey-washing graffiti on a concrete wall. Wait a second! That’s giving?

What assumptions is Curves making here? And can we take those assumptions seriously?

Maybe the people at Curves think graffiti is vandalism, or that it’s something that happens when gangs get their hands on cans of spray paint.

Or maybe it’s all a matter of interpretation. While there’s no question that some tagging may be gang-related, mural graffiti belongs to a different category altogether and might be viewed as:

• art

• social criticism

• symptoms of social dis-ease

• prophecy

• narrative

We define art, not by any rules of aesthetics, but through institutional forces of legitimation. Those with the power to do so (e.g. legislators and ad agencies) determine what counts as art and what as vandalism. But the difference is often vague and requires a more discerning eye than many legislators possess. This difference has played itself out most starkly in the story of Alan Ket who was arrested in New York City last year and faces 14 charges and a potentially lengthy jail term because his tag has been associated with graffiti discovered on walls and subway cars. Yet at the same time he has worked as artistic consultant to companies like Atari, Moët & Chandon and MTV. View him speaking about the issue on YouTube and read about the charges he faces in this April 19, 2007 NY Times article.

It is unlikely that Canadian graffiti artists would encounter such draconian legal sanctions. See for example the story of Victor Briestensky, 20, arrested last month in Saskatoon. He faces two counts of mischief under $5,000 and a four counts of breach of recognizance. Not exactly attracting the same order of sanctions which Alan Ket faces. The difference may lie in cultural perceptions of the meaning of property. In the U.S., so-called eco-terrorist Jeff Luers was sentenced to 22 years and 6 months for setting fire to 3 SUV’s in protest of America’s contribution to global warming. The debate continues whether the length of his sentence was a function of the “terrorist” label or the tendency within capitalist ideology to elevate the principles of property and ownership to absolute values (or both). Canada, with a longer history of socialized thinking, may have evolved a more relaxed attitude towards painting other people’s property without permission. To the extent that graffiti is, by definition, a critique of capitalism (because it subverts the authority of property–owners), it will naturally receive a harsher response in the U.S. At the same time, its value as meaningful public discourse and debate is much higher. After all, those who risk greater sanctions must believe in the importance of their work, and those who are willing to punish with an iron first must believe their interests are truly threatened.

I applaud Curves for its efforts promote well-being from a holistic perspective. But if we are to be truly holistic, let’s remember that our body includes a social body. Grey-washing hides something that needs to be seen. It signals unrest, dis-ease, disenfranchisement, powerlessness. Grey-washing is effectively a refusal to listen and a denial of social problems. The social body is emphatically not whole, and the Curves ad identifies its middle–class clientele as a group which sees only superficial solutions and calls it “giving back.”

Beyond values of aesthetics and property, there may be a spiritual dimension to graffiti. In one sense this is a trivial statement because all self-expression has a spiritual dimension. But it’s possible to give a liberationist spin to graffiti—giving a voice to the voiceless—offering alternative means of expression to those who lack access to mainstream media—drawing attention to needs that would otherwise go unnoticed—creating community in a landscape skewed in favour of alienation.

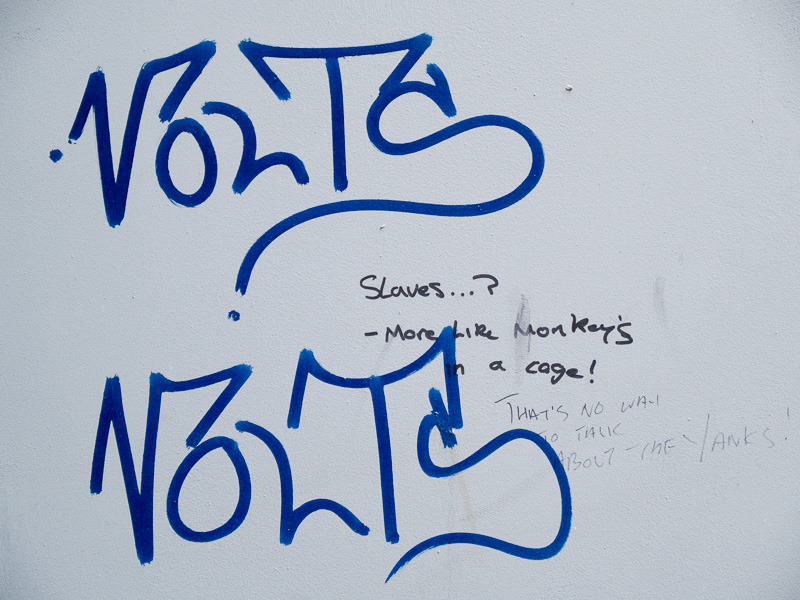

To illustrate my point, I offer below some examples of graffiti I saw recently in Scotland. The first was in the east end of Glasgow by the Lodging House Mission. The second was in an alley behind Sauchiehall Street also in Glasgow. And the third was in the Advocates Close in Edinburgh, with the following writing between the two tags: “Slaves … ?—More like monkeys in a cage!” “That’s no way to talk about the yanks!” In symbolic terms a history-laden lane is an ideal location if you wish to send an informal spray painted message to the arbiters of power.

Finally, graffiti may be a narrative. In an interview, Alan Ket refers to it as “writing art.” Certainly much graffiti incorporates text. And the association between text and design has long been recognized. American type designer Frederic Goudy once said that “[a]nyone who would letterspace blackletter would steal sheep”—and sheep stealing, back in those days, was a big deal. The “crime” may not be graffiti, but bad graffiti. Good graffiti is the fusion of text and design, narrative and aesthetic. Or maybe the “crime” is the blank wall, architecture that denies the reality that all buildings ought to serve people, not alienate them. Graffiti as text affirms the fact that even the most austere constructions are home to stories and are only meaningful when those stories get told. Graffiti is a clearing of the throat. A way to signal that bigger narratives lie like mortar between the bricks and sink like footings deep into the ground.