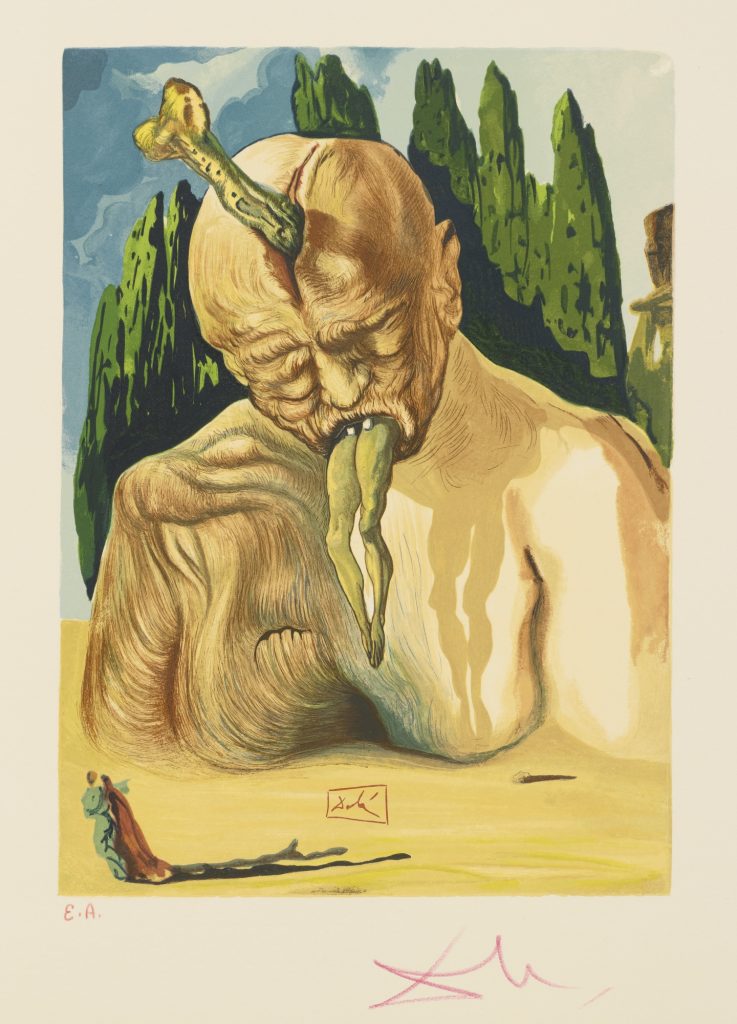

A while ago, at an art auction, I purchased a single Dali wood cutting from a series of 100 prints to commemorate the 700th birthday of Italian poet, Dante Alighieri, in 1965. It is from Les Heures Claires edition of 4,765 books. Before you get all excited and say “Ooo, he has a piece by Dali,” make sure you note the last paragraph of the description: “Prices suffered heavily under the reports of fake Dali prints. And therefore original Dali art prints can be purchased for rather modest prices.” And so, no, I did not hand over thousands of dollars for the piece, nor did I buy it as an investment. Instead, I bought it because I like Dali, and more importantly, to gross out my wife. Whenever guests sit in our living room, the print hangs there as a challenge. “What the hell is that?” they sometimes ask. And I explain that it was inspired by 14th century Italian poetry. “It looks like some guy just got his head split open and he’s throwing up a lot of green shit.” “Well,” I answer, “not all poetry from the Italian renaissance was about god or love or roses.”

The story of the print’s creation (like the story of most wood cuttings) is instructive. Purists, if that’s what they’re called, claim that such prints are never original—although what they really mean is that the prints are never solely by their creator.

Wood cuttings are a collaborative effort. In this case, Dali began with a series of water colours. These became the “guidelines” for two men who carved 3,500 blocks of wood for the prints. Some say that the process has legitimacy because the artist is present throughout the process, from the first glimmers of inspiration within his brain until the last block presses its ink onto the last page. But let’s be real. A man of Dali’s reputation was too busy to bother, and so he probably entrusted the production entirely to his assistants.

Being busy is not the only reason that artistic production becomes collaborative. I recently heard that Bruckner was so insecure in his musical abilities that, before publishing one of his symphonies, he asked a student to make major revisions. Or, moving right to the brink, Andy Warhol licensed his name to B movies (think Dracula). He had nothing to do with their production. Probably the only motivation was the licensing fee.

But collaboration may well be necessary to the survival of all artistic production. There is the collaboration of teacher and student, master and apprentice. Without these collaborations, there would be no opportunity to nurture a new generation of artists with the necessary skills, talents, and positive encouragements.

Going even further, the notion of an artist engaged in the independent production of a work may be wholly illusory. Even if Dali had carved the wood blocks himself, would my print really have been produced by him? Where did Dali’s surrealism come from? Did it spring from his head as if he were a god creating a world ex nihilo? I suspect a different account. I suspect that Dali’s particular method, his peculiar mode of being, arose from a commitment to earnest conversation with those who went before him. Growth is a kind of conversation: taking all you have learned from your parents and your mentors, then answering them with something fresh. Rebellion is a kind of conversation: taking all you have learned from those who went before you, then answering them with a grand rejection. No doubt, Dali conversed in both these modes, and many more besides. We all do, wherever it is we choose to direct our passion.

I carry with me a deep commitment to my culture. Most of the time, I can barely make it out. Sometimes I hardly know it. Sometimes, I look at the world we have created, all of us together, and it enrages me. At other times, after I grudgingly acknowledge that I am fully part of it, I am driven to find in it a core of meanings worth preserving. Maybe this is where the artist looks. Whatever else may be said of this place, it does not spring from within the dark recesses of the artist’s solitude; it springs from his communion with the world.