What do the British Museum and the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) have in common? Not much it seems. Certainly not much when it comes to thinking about culture-as-collaboration and online file-sharing.

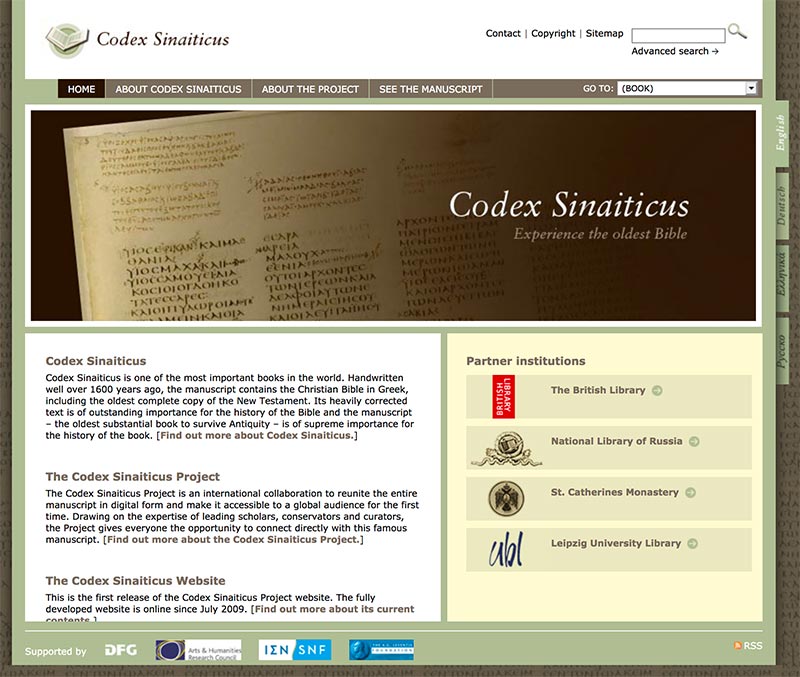

Yesterday, the British Museum completed the Codex Sinaiticus Project with the launch of its web site which provides free online (hi-res) access to one of the most important primary sources used to construct the Bible in its modern form. The Codex Sinaiticus consists of 800 pages and fragments which are currently spread across four different institutions: the British Museum, Leipzig University Library, the Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai, Egypt, and the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg. The web site gathers all the fragments under one virtual roof, making it more convenient for scholars (and nerdy koine amateurs like me) to examine the codex. It is noteworthy that 1) like the Bible itself, this project is a collaborative endeavor; 2) it springs from, represents, and feeds an entire people; 3) it is freely available to everyone — not just academics who pay a subscription fee, not just citizens of those countries whose tax dollars funded the project, but everyone.

In a completely unrelated story, a 32-year-old woman named Jammie Thomas-Rasset from central Minnesota has appealed the decision to fine her $1.92M for downloading 24 copyright protected songs using Kazaa. Last month, in a suit filed by the RIAA, a U.S. District Court ordered the woman to pay $80,000 per song. The RIAA did not offer evidence to indicate whether the defendant had, in fact, caused $1.92M in damages to the recording companies which the RIAA represents. Instead, it opted for statutorily prescribed damages. However, the RIAA did suggest that the damages were more significant the $24 worth of tracks which Thomas-Rasset downloaded because the woman used Kazaa which allowed for the viral distribution of other copyright protected tracks.

I wonder if we might scour the ancient pages of the Codex Sinaiticus for some passage to characterize the RIAA’s conduct in this proceeding. How about something from Gen 22 where God asks Abraham to make a human sacrifice? Or how about something from John 19:18 where Pilate orders a crucifixion then puts an inscription on the cross? I think it was RIAA, wasn’t it?

While I have no doubt that Jammie Thomas-Rasset is an evil person, her punishment lacks proportionality. I thought we had moved beyond the primitive impulses that make an example of one person before her peers (this is called “general deterrence” but is only one of several factors which are supposed to be considered when formulating a just punishment). It seems inordinately cruel to offer wares in a digital (infinitely replicable) format, raise young people in an environment where infinite replicability becomes a cultural norm, then punish with an iron fist those behaviours which have become a cultural norm and which you encouraged.

Lawrence Lessig and Siva Vaidhyanathan (whose books I review here) see the problem as a conflict between the fact that on the one hand cultural production is inherently collaborative, and on the other hand we incentivize cultural production through a rights-based legal regime that assumes a single identifiable “creator/owner.” Both authors propose alternative regimes which preserve incentives to produce cultural works while avoiding the draconian consequences of property rights ideologues like the RIAA.

Afterthought: I suppose the RIAA could always argue that there is no copyright on the Codex Sinaiticus, which is true unless you believe its author is God. Thanks to the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, copyright in the U.S. persists for 95 years following the year of an author’s death. Hmmm. Let’s do the math. God was reported dead by Nietzsche in The Gay Science in 1887. 1887 + 95 = 1982. The Bible entered the public domain on Jan 1st, 1983. Looks like we’re in the clear. (I’m assuming of course that God was American.)