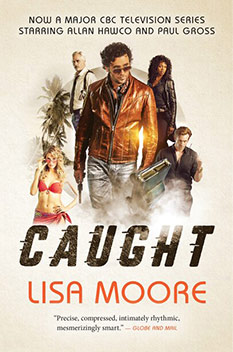

Caught is a bit of a departure for Lisa Moore insofar as it is more plot driven, less concerned with the investigation of interior experience. One might go so far as to say it is more commercial, and this is confirmed by the fact that the cover of my edition declares that Caught is now a major CBC Television series starring Allan Hawco and Paul Gross.

Twenty something David Slaney has just broken out of a Nova Scotia prison and is on the run. He had been incarcerated for trafficking in a controlled substance. Because the amounts in question were significant (two tons of marijuana shipped by boat directly from Colombia), the authorities have more than a passing interest in recapturing Slaney. However, the authorities aren’t the only ones with their hooks in him; because the shipment was financed, Slaney’s backers still expect payment for their lost product and the only way he’s ever going to meet his obligations is by smuggling another shipment of marijuana into the country. To that end, Slaney has to make his way across the country to Vancouver where he will meet up with his old partner, Hearn, who uses his status as a Ph.D student in literary studies as a front for his drug trade, or maybe it’s the other way around. Hearn will connect him with a guy named Carter who has a boat and together Slaney and Carter will sail south to Colombia.

A few observations:

Homer

Moore grounds the novel in Homer’s Odyssey. There is the general parallel: Slaney treks across the country and down the coasts of North and Central America, meeting weird and wonderful people and having adventures along the way. But there are more specific references too. The story is set in 1978 before law enforcement had access to sophisticated GPS and satellite imaging technologies so, to track the boat’s course, the RCMP relies on a big satellite dish described as the eye of God. It appears in a section titled “Cyclops.” In case there are any doubts that this Canadian crime drama has at least one foot in Ancient Greece, we have these thoughts from Patterson, the officer in charge of the pursuit:

A dish, an eye, a cyborg or Cyclops, and perhaps Patterson was the only man in the room old enough, besides O’Neill, to wonder about the hubris.

Curiously, many of the people Slaney meets do not have two eyes that are the same; Moore’s fictional population suffers from an epidemic of heterochromia iridum.

Polyphemus continues to rear his ugly one-eyed head as when the smugglers come ashore in Colombia and meet their contact there. They stay until after dark, eating and drinking, and then Slaney sets off in search of the pit toilet:

A chicken’s head lay in the dirt, and when the flashlight beam strayed to it, the chicken’s yellow eyeball with its black pupil and red warty-looking eyelid stared at Slaney, unblinking. The eye looked full of consternation and acceptance.

In the end Polyphemus lost his one eye to the trickster, Odysseus, and we witness the same end here in Caught. Twenty years after the novel’s present time, Slaney reconnects with Ada, the girl who had tagged along with Carter on their boat ride down to Colombia, the same girl who subsequently gave them up to the police. They meet in Ada’s apartment where she introduces her cat whose eyes have been removed because of glaucoma.

The Cyclops is not the only Homeric reference. On the voyage home, we hear the Sirens. A storm overtakes the boat and because Carter is perpetually drunk, it falls to Slaney to take down the sails. He lashes himself to the mast as the boat tosses him one way and then the other, yet like Odysseus he survives.

Aeschylus

When Caught isn’t being a Homeric epic, it’s an Athenian tragedy. Given the title of the novel, it doesn’t spoil anything to note that we know precisely where this story is headed. Lisa Moore writes with a light touch, so the story isn’t weepy with pathos. Nobody is going to die for a few bales of marijuana. But it follows the tragic template insofar as we know from the outset that our hero will never succeed. While watching a bullfight, we have this from Slaney:

He loved that the fight was fixed. Every step planned and played out. Always the bull would end up dead.

It was the certainty that satisfied some desire in the audience. The best stories, he thought, we’ve known the end from the beginning.

Patterson, his RCMP nemesis, knows where he is at every step of his journey (except in the storm) and uses him as a means to the more important players in this game. There are times when Slaney suspects that his narrow escapes are a little too easy and he appears to be on the cusp of an awareness of a dawning of a realization that maybe he’s being set up. But always he pulls back from a slide into cynicism and affirms his trusting nature. In the upside down world of criminal enterprise, Slaney’s tragic flaw may be that he is innately good. While Slaney and Patterson (posing undercover as Brophy) meet on a beach, they see a woman struggling in the water and at risk of drowning. Without a thought for himself, Slaney dives into the water and rescues the woman. Meanwhile, Patterson shrugs off his apparent indifference by saying he has a heart condition. As Ada observes during their later meeting:

What I found astonishing, she said. How easily people believe a lie. Isn’t it something?

It’s a cynical view of life to which Slaney has no access.

Hi and Lo

If you want to, you can read Caught as a commercial romp, characters in Elvis T-shirts holding drinks with plastic umbrellas. At the same time, Lisa Moore leaves traces of something else if you prefer. Think of Slaney’s partner, Hearn, the drug dealing Ph.D candidate. He has one foot in two different worlds. There’s a flexibility at play here that doesn’t thumb its nose at plastic umbrellas just because they don’t have literary heft. In this regard, Caught reminds me of books by Paul Quarrington, most notably The Spirit Cabinet and Civilization and My Part in its Downfall, or Jesus’ Son by Denis Johnson, books that tread the narrow path between pulp fiction and the English Department syllabus.

My take on Lisa Moore’s first novel, Alligator