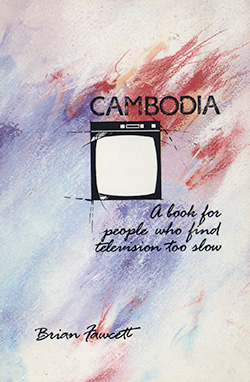

Marshall McLuhan summarizes his book, The Gutenberg Galaxy, with: “The theme of this book is not that there is anything good or bad about print but that unconsciousness of the effect of any force is a disaster, especially a force that we have made ourselves.” The paradox of this statement (or its Catch-22) is that a medium functions by carving off and emphasizing one sense over all the others and this has a hypnotic effect that makes it impossible for us to see the effect it produces. So how do we avoid the disaster of living unconscious in the media that wash over us? One way is to explore what people have said at earlier stages in the development of media. And so we have Brian Fawcett, writing in 1986 on the fulcrum between television and internet, to offer guidance on how to think about the media that blind us.

Subtexts are bogus

Fawcett opens with a brief epigraph in which he challenges the modern assumption that “artistic reality is secured by subtexts that trail in all directions”. He challenges the role of the critic, or even of the academic, as interpreter of these subtexts to the ordinary reader/consumer. At first, the reason for his disdain was obscure to me. But it was apparent that he was drawing on/applying/extending the thinking of McLuhan, so I read The Gutenberg Galaxy and discovered for myself why Fawcett’s disdain might not be so outlandish after all.

McLuhan held nothing but contempt for the idea of the “unconscious” mind.

McLuhan’s theory is that the rise of mass-produced print effected a cultural shift from the audile-tactile of oral societies to the visual of Western Europe, a state of affairs that persisted until 1905 when Einstein announced that space is curved. The shift to print media carved the visual from the other senses. “Since print allowed only a narrow segment of sense to dominate the other senses, the refugees had to discover another home for themselves.” McLuhan describes this refuge as “the ever-mounting slag-heap of rejected awareness.” This is the unconscious, the hidden life of the mind which Freud and Jung “discovered” and interpreted back to the world. However, they discovered what was never lost. In oral cultures, myth—which seems so strange to us now—is strange only because it holds all the senses in awareness simultaneously. There is no unconscious mind except as we have constructed it.

Cambodia as subtext

Fawcett undertakes to write a book about (post)modern culture which has no subtext. He does this by splitting each page in two. The top half is his text. The bottom half is his subtext, which he uses to make explicit whatever we as readers might think is motivating/driving/informing the top half. The bottom half boils down to a single word: Cambodia. More precisely, that period of Cambodia’s history when Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge committed a genocide resulting in as many as two million deaths.

Fawcett’s book asks a single question: how can anybody with artistic aspirations function in a world where there is Cambodia? Had he written his book a generation earlier, he might have called it Germany. Later, he might have called it Bosnia or Rwanda or Sudan or Afghanistan or Syria. He observes: “the continuous growth of authority and bureaucracy is a universal phenomenon of modern political life. But bureaucratic authority has a most unexpected twin: genocide.”

What does it mean to be an author?

The problem with the word “author” is that it is the root of the word “authority” and expresses the danger that wordsmiths may be drawn into the machinery of political authority. There is a paper-thin divide between a love sonnet and propaganda. While we tend to think of authors as practitioners of the liberal arts, the history of literature is illiberally sprinkled with instances of political whiplash. Ezra Pound wrote radio broadcasts for fascist Italy. David Mamet committed a stunning reversal with the publication of The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture. And the novelist, Mark Helprin, responded to his loss of internet troll virginity with Digital Barbarism: A Writer’s Manifesto, which includes numerous statements in much the same spirit as this:

In primary and secondary schools, writing, a naturally individual act, is now taught as such a collaborative exercise. It is often assigned to teams. Students gather and “brainstorm” (a comic-book word) to decide topics and approaches. They submit their work to what are in essence factory-floor soviets, and are bound by every manner of political inhibition and prohibition as if they were composing essays in a luxurious Vietnamese reeducation camp.

Several generations of students have been subjected to this. The preeminence of the collective was drilled into them in their earliest and most impressionable years as surely as they were made to study the same things about Martin Luther King in one grade after another, as if the worst possible fate for a child would be to forget what he had learned about Martin Luther King the year before. Intense “communitarianism” is continued through elementary and secondary education, and then nailed firmly into the wood by experts, ideologues, and lunatics in the university.

As a Canadian blogger, it’s neither here nor there to me, but if I had to guess, I’d say Helprin is a Republican. Doubtless, Fawcett would share Helprin’s abhorrence of the (Cambodian) reeducation camp, but Fawcett might differ to the extent that he sees no distinction between left and right when it comes to wielding authority. In his view, they are equally capable of killing in the name of civilization and progress.

Irony as Procedure

In effect, Fawcett runs two distinct narrative lines and they vibrate off one another. Sometimes, they vibrate in harmony. Sometimes, they set off a discordant jangle—the jarring tone of irony. The top line reads like reportage, it is familiar, concrete, “low”. The bottom line reads like material in an academic journal, it is formal, abstract, “high”.

On Top

On top, we have:

• a meditation upon the perspectival fact that a man’s penis looks shorter than it actually is if viewed from above which creates performance issues when trying to urinate in public washrooms;

• a confrontation between Reggie Jackson and a man who demands that Jackson punch him in the face;

• Marshall McLuhan has a chat with St. Paul about how he’s going to promote his messiah (as opposed to all the other messiahs competing for attention);

• a marvellous tale of two Asian-looking German POW’s captured by the English who had lost their way from Tibet fifteen years earlier and had survived because they believed they were dead;

• a development proposal for a facility to house destitute professionals;

• the mysterious disappearance of a bar owner who had blown up the town’s satellite feed because unbridled TV-watching was destroying his business;

and so on.

As Fawcett observes at the end of one account: “Sorry about not having a nice ending, but it’s the world we live in that prevents that. We have all the information and all the sensation, but none of the stories we hear quite add up. They just pile up, a different kind of assault altogether.” Increasingly, that describes our encounters with media. A pile up. An assault.

On Bottom

Simultaneous with the anecdotal pile up on top, Fawcett offers an extended meditation upon Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge on the bottom of his pages. He is chiefly concerned to tease out all the ways in which the Khmer Rouge sought to destroy memory and imagination. It was never enough simply to kill people.

But he begins his investigation nearly ninety years earlier with another author/authority for whom he feels a great affinity—Joseph Conrad. In 1890, Conrad was sailing to what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo when he saw a French warship shelling the coast for no reason. In the following months, he witnessed the effects of what is possibly the worst genocide in human history. On his return from the DRC, Conrad gave up his romantic plans of life as a merchant marine, and chose, instead, to write in relative isolation. He may have asked himself a question much like Fawcett’s: how does one create art after the Congo?

Although abhorrent, the structure of the Congo genocide is decipherable; it follows the pattern typical of colonialism. A modern power seeks to civilize a primitive culture and wipes out all that it views as backward and tribal. But the situation in Cambodia was different. There, the Khmer Rouge railed against civilizing influences like literacy and education and sought to return the country to its tribal roots. What the two atrocities had in common is that the acts of violence manifested a deeper desire to eliminate a mode of consciousness.

Cambodia and TV

In The Gutenberg Galaxy, McLuhen theorizes that while the shift from oral culture to print media suppressed the audile-tactile modes of consciousness in favour of the visual, the shift from print to electronic media is well on its way to effecting a shift in the opposite direction. There is a sense in which, like the Khmer Rouge, we are all moving to a tribal consciousness. We all live in Cambodia.