Recently, the CBC rebroadcast Eleanor Wachtel’s Writers & Company interview with Zadie Smith originally broadcast in 2010 to coincide with the release of her book of essays, Changing My Mind. In the interview, she discussed views she had aired in some of her pieces, views which, in my estimation, have come to roost in her 2023 novel, The Fraud.

So, for example, she spoke of her admiration for George Eliot’s Middlemarch and her discovery on subsequent readings that what she had taken seriously as a young reader, George Eliot may in fact have offered as parody; she had simply been too young or too inexperienced to detect the ironic distance the writer placed between herself and her principal character, Dorothea. Only with a more mature reading did Smith recognize that Dorothea’s relentless devotion to serious issues makes her a ridiculous figure.

In The Fraud, Smith pays homage to Middlemarch with a brief chapter (they’re all brief) titled “Contemporary Fiction.” The big-nosed Mrs. Lewes (George Eliot’s partner was named Lewes) makes an appearance at the trial of the Claimant to the Tichborne baronetcy. By coincidence, the trial happens shortly after the publication of Middlemarch, which the principal characters of Smith’s novel, Eliza Touchet and William Ainsworth, have been reading when not attending the proceedings. Touchet claims to be enjoying it, but Ainsworth can’t get past the first volume and complains, as have so many after him, about its length. At that time, it was typical for novels to be published serially in three volumes whereas Eliot’s major oeuvre appeared in eight. In a later chapter titled (surprise, surprise) “A Question of Length”, William Ainsworth complains to Mrs. Touchet about the length of the Tichborne trial and asks how long she thinks it will be. “Mrs Touchet shrugged her shoulders. Her private and silent approximation was: about eight volumes.” And then there’s The Fraud, itself, which Zadie Smith has organized into eight volumes. Clearly, during its writing, Smith was suffering from Middlemarch on the brain, although I can think of worse afflictions.

But that’s only the beginning of Ainsworth’s complaint about the big-nosed Mrs. Lewes:

No adventure, no drama, no murder, nothing to excite the blood or chill it! I must say I can’t understand the glowing notices. As if she were a new Mary Shelley! But there isn’t an ounce of Shelley’s imagination. Just a lot of people going about their lives in a village – dull lives at that.

Although published in 1872, Middlemarch was set in the period from 1829 to 1832. This span—from setting in 1829 to publication in 1872—coincides with the period under scrutiny in The Fraud. Middlemarch had, in part, concerned itself with social changes wrought by the rise of industrialization and the destabilizing effects of the market economy that industrialization enabled. Although Eliot’s novel never explicitly explored the matter, lurking in the background was the question: if industrial automation made machine output more efficient than manual labour, then what justification remained for slavery? Indeed, abolitionists achieved a major milestone in 1833 when the UK passed the Slavery Abolition Act, to take effect the following year. However, the new legislation didn’t signal a perfect arrangement; for one thing, existing obligations were grandfathered, meaning that slavery persisted in the UK and its colonies long after its official repeal. In other words, slavery persisted all through the period when William Ainsworth was writing his novels, and entertaining his literary friends like William Thackery and Charles Dickens, and engaging in sporting sex with his cousin, Mrs. Touchet.

In the interview with Eleanor Wachtel, Zadie Smith also made much of the fact that when she was a teenager, her mother routinely passed her books written by Black women. Most influential was the writing of Zora Neale Hurston, and for two reasons. First, Hurston didn’t feel constrained to write only about Black experience. That has given Smith permission to write more freely while avoiding the absolutism that seems to taint so much of contemporary identity politics. Today’s literary equivalent of the one drop rule dictates that if you have the least bit of Blackness in your ancestry, then somehow you’re obliged to write about Black themes and little else. And so Hurston is vilified in some quarters for the fact that she wrote a novel featuring only white characters.

As The Fraud opens, it seems as if Smith is bent upon following the same path. The first chapter presents the Ainsworth household in a state of chaos. The upstairs has collapsed into the downstairs thanks to the weight of so many books, and Mrs. Touchet has summoned contractors to fix the disaster. Meanwhile the household is overrun by three young daughters. We learn that their mother died in childbirth and their father’s cousin, Mrs. Touchet, with limited resources of her own, has stepped in to provide care and stability for the children in exchange for a roof over her head. There are hints of occasional trysts (happily unfettered by the usual Victorian repression) but William Ainsworth ultimately marries the much younger Sarah. So, for the first third of The Fraud, the narrative seems all very English, all very Victorian, all very white.

Zora Neale Hurston was influential for another reason, too: the naturalness of the language she uses in her fiction. Curiously, there is little evidence of this influence in Smith’s own writing. The opposite, in fact. In order to portray a white Victorian family dominated by a man of letters, Smith has used language that, by today’s standards, strikes us as stiff and overwrought. William Ainsworth was a historical literary figure (you can download some of his works from Project Gutenberg) but a bit of a hack who nevertheless prided himself on the fact that at one point, for a few weeks, he outsold Oliver Twist. Although, he hobnobbed with the likes of Charles Dickens, he was clearly a writer of the second rank who gravitated naturally to writers like Bulwer-Lytton (who makes an appearance at one of his dinner parties). You may recognize Bulwer-Lytton’s most famous sentence which opens his 1830 novel, Paul Clifford, and has been immortalized by Charles Schulz through his dog, Snoopy: “It was a dark and stormy night.” The same sentence inspired the annual Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest in which writers vie for the honour of composing the worst opening sentence imaginable. Presumably, William Ainsworth could give contestants a run for their money given that R. H. Horne, in his 1844 survey of English authors, describes his work as “generally dull, except when it is revolting.” In the presence of so many hacks, Zadie Smith is clearly enjoying herself; we readers should keep in mind her observation about Dorothea in Middlemarch: never take these characters as seriously as they take themselves.

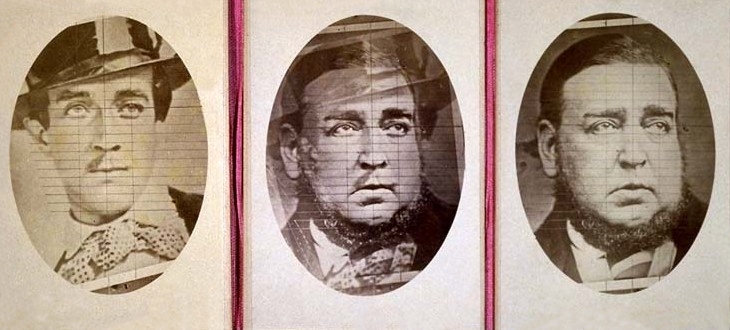

As a backdrop to family life in the Ainsworth household, we have the Tichborne trial, which became a cause célèbre in Victorian England and consumed endless hours of dinner table conversation and public house debate from Penzance to Wick. Sir Roger Doughty Tichborne, heir to the Tichborne baronetcy, had been aboard a ship that went down in 1854. Although no body was recovered, he was presumed dead. Dead, that is, until a butcher in Wagga Wagga named Thomas Castro came forward twelve years later claiming to be the lost heir. Subsequent investigation revealed that Thomas Castro was Arthur Orton, son of a butcher from Wapping. Whatever his identity, the man held fast to the claim that he was, in fact, Roger Tichborne notwithstanding the fact that he had forgotten the French language although fluent since childhood, had acquired a Cockney accent despite his upper class education, had transformed from a thin man into someone obese, and, inexplicably, had grown earlobes. The Claimant, as the man came to be known, had his day in civil court, and afterwards, became the defendant in criminal proceedings on charges of perjury.

The rational Mrs. Touchet can see no other interpretation of events: the Claimant is a fraud. Nevertheless, there are two things about the matter which disturb her. The first is the Claimant’s Black manservant and principal witness, Andrew Bogle. This man is loyal to the Claimant and utterly compelling. Taken alone, the Claimant can’t be anything other than absolutely fraudulent. Similarly, taken alone, Bogle can’t be anything other than absolutely honest. The conflict between these two views sets up a cognitive dissonance which Mrs. Touchet doesn’t know how to resolve. She finds that “it was possible to ‘know’ Sir Roger was a fraud and yet still ‘believe’ Bogle.” It’s almost as if she’s stumbled upon the judicial equivalent of Schroedinger’s Cat. The Claimant simultaneously is and is not the true heir of the Tichborne baronetcy, and until the pronouncement of the verdict, both possibilities are true.

So compelling is Andrew Bogle, that Mrs. Touchet must seek him out and learn what she can of his story. This forms a good portion of the novel’s middle third, as we eavesdrop, in a manner of speaking, on Bogle’s account of his father’s capture by slave traders and of his own life growing up on a plantation in Jamaica. As with naturalness of language, we see that Zora Neale Thurston’s influence viz. writing white hasn’t really stuck; Black experience has a place in The Fraud after all.

The other matter which disturbs Mrs. Touchet is the readiness with which Sarah, William Ainsworth’s young wife, is willing to accept every last thing, no matter how outrageous, that issues from the Claimant’s lips. In conversation with Sarah, Mrs. Touchet trots out the usual tools, like Occam’s Razor, that people steeped in reason tend to apply to fresh assertions. But Sarah appears impervious. In fact, she goes further, actively supporting the Claimant by contributing to his legal fund. She rationalizes her support in the face of an obvious grift by observing that the Claimant is really just an ordinary person like her, complete with Cockney accent and no discernible education. We learn that Sarah is illiterate. We learn, too, that she entertains conspiracy theories:

Sarah now extemporized on the ‘shadowy Freemasons’ who ‘run the Old Bailey’ and the ‘bitter Catholics’ who pay the bribes to the Freemasons who run the Old Bailey, and the ‘Hebrew moneylenders’ who earn a guinea for every soul thrown in Newgate.

Claimant supporters even go so far as to support an anti-vaccination movement. Mrs. Touchet intercepts various memorabilia Sarah has ordered to support the cause: “Tichborne Toby jugs and figurines, Tichborne pamphlets and newspapers, a Tichborne biscuit tin with a badly drawn portrait of the Claimant upon the lid.” But perhaps most telling is Mrs. Touchet’s observation that Sarah doesn’t share her husband’s sense of humour.

At this point, it should be apparent that although Zadie Smith purports to have written a historical novel, we can simultaneously read it as an allegorical tale for our own age. It’s Schroedinger’s Novel, both historical and contemporary in the same reading. Sarah could just as easily be a MAGA Republican who decries Trump’s critics, orders Stop The Steal merchandise, and rationalizes it all from within a world view that flips reason on its head. But the tell, the way we distinguish our world from Sarah’s world, is that hers is filled with the sort of sincere belief that allows no room for humour. Yes, there is the sort of humour that counts as gaslighting—just joking; can’t you take a joke?—and the humour of cruelty that plays out at someone else’s expense. But what goes missing is self-deprecating humour grounded in empathy.

And that, my friends, is how I know I can trust Zadie Smith. Her latest novel rests upon a foundation of empathy and deep humour. While touching on serious concerns, it is a funny novel. That alone assures me that she and I share enough assumptions about the real world that I can read her novel without feeling that she’s perpetrating a fraud. And so, to my final observation.

Ostensibly, the fraud of Zadie Smith’s novel is the grift that Arthur Orton uses to fleece his supporting public. But the novel also raises a question about William Ainsworth’s writing: if you sell badly written books, isn’t that also a species of fraud? Smith raises this question repeatedly. In a moment of frustration during a conversation about Dickens, Mrs. Touchet exclaims: “‘Oh, what does it matter what that man thinks of anything? He’s a novelist!’” And later: “God preserve me from novel-writing, thought Mrs Touchet. God preserve me from that tragic indulgence, that useless vanity, that blindness!” Finally, when confronted with a parody of his own writing published by Edgar Allen Poe, Ainsworth turns to his cousin and asks: “‘Is he making fun of me, Lizzie? Am I a fraud?’”

Self-doubt is an occupational hazard and I have no doubt Zadie Smith has asked the same question of herself from time to time. So it takes a great deal of chutzpah to lay that question at the feet of your readership, especially in the context of a work that places you in conversation with so many luminaries (and a few not so luminous luminaries). I’m sure she doesn’t need my reassurance, but I’ll offer it anyways: a resounding affirmation. The Fraud sparkles. It is a true gem.

See other Nouspique posts on Zadie Smith:

Review: The Wife of Willesden, by Zadie Smith – March 23, 2023

Positioning Zadie Smith’s NW in Space and Time – June 7, 2022

Zadie Smith’s Reliance on Negative Capability in Feel Free – May 17, 2022

Zadie Smith and Intimations of “Real Suffering” – July 30, 2020

Swing Time, by Zadie Smith – June 3, 2020

Photo Credit: The Tichborne Tryptich is in the public domain and can be downloaded from Wikimedia Commons.