A cousin recently posted a rant on Facebook. He went on at length about being tired of other people feeling entitled to live off the backs of hard working people like him. While he avoided certain key words, it was clear where he positions himself on the political spectrum. He doesn’t like having to pay taxes to support socialized benefits, doesn’t trust the government, and hasn’t got much love for immigrants. It’s pretty standard fare for an aging white man who lives in small town Ontario, drinks with his buddies at the Legion Hall, and finds affirmation for his world view whenever he goes to the local chapter of his lodge. After I read the post, and saw all the thumbs-ups and hearts and supportive comments from like-minded people, I shook my head and asked myself a non-obvious question which I share here:

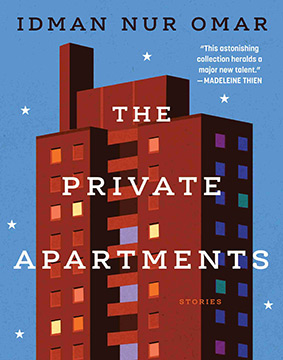

What would it take for me to persuade this cousin to read Idman Nur Omar’s debut collection of short stories?

I think this may be more in the nature of a rhetorical question and I don’t seriously believe I’ll come up with an answer. I might just as easily ask why rain is wet. In many respects, Idman Nur Omar is the anti-cousin: not white, not male, not born here, not Freemason, not Christian. Despite all the nots, it’s possible for aging white men to enjoy and relate to Omar’s stories. I’m proof of that. I’ve taken up Omar’s collection of stories without suffering an allergic reaction or crisis of identity or threat to my emotional stability. Quite the opposite, in fact. One day, it might be interesting to explore more fully the question why some aging white men are willing to read beyond their own experience while others prefer the comfort of an echo chamber, but that’s a post for another day. To explore it here would distract from the most important matter at hand: the writing.

I first encountered Idman Nur Omar’s writing in issue #110 of Brick Magazine which published one of the short stories that appears in this collection, “Amsterdam 2008”. She tells this story from the point of view of a young Dutch-born Somali girl whose mother over-involves herself in the life of an elderly compatriot named Rashid Barre. The woman’s motivation is unclear, but the fact that she insists her daughter address the man as Awoowe (grandfather) is suggestive. The woman cleans the apartment, helps with the grocery shopping, cooks meals, and deals with a leaking pipe. Occasionally, curiosity gets the better of her and she asks awkward questions. She is particularly concerned about his children and has formed the opinion that they have abandoned their father in Amsterdam while going on to make good lives for themselves in America. She worries that the eldest daughter has simply abandoned all responsibilities. The mother is inclined to be judgmental and a little self-righteous, but before she can embarrass herself, she learns that Rashid Barre’s relationship with his children is more complicated than appearances suggest. They may not be as irresponsible as the officious mother has supposed. Here, Omar delivers a slice of social comedy with a deft touch.

As the collection’s title suggests, a unifying trope is the apartment which is the primary setting for most of the stories whether that apartment is situated in Rome or London, Amsterdam or Dubai, Toronto or even Welland (Ontario). There is something impermanent about an apartment. Despite the occasional article by an economist who claims it makes more sense to rent an apartment, especially in a wildly expensive housing market like Toronto, nevertheless there is a prevailing attitude that favours home ownership. Apartments are for immigrants and refugees and students. Apartments are for single mothers with squabbling children and empty fridges. Apartments are one step away from what we now charitably call precarious housing situations.

An apartment represents more than simple transience. An apartment has a generic quality, too. With standard sheets of drywall, mass produced fixtures, factory milled flooring, an apartment in Rome could pass for an apartment in Amsterdam could pass for an apartment in Toronto. The pro forma trappings of a marginal life threaten to deaden the soul. If it isn’t apartments, then Omar’s characters take us to other generic non-places like malls and airports and downtown offices. And always, the ubiquitous smart phone, with its shining screen and its Candy Crush promise of refuge from life’s sameness.

Even for those who escape the rental hamster wheel, the generic quality of consumer culture follows them in unexpected ways. In “Toronto, 2011,” the legal assistant, Amira, looks on, puzzled by the relationship between her boss and his beautiful wife. Brock is a successful corporate lawyer, Black, from an unspecified Caribbean island, possibly Anguilla as that’s where his grandmother lives. He seems to have it all. There’s the Maserati, big house in Richmond Hill, two children, and a wife named Beverly who was once Miss Bermuda. However, Brock appears to have a thing for blond women. What could more generic than an office affair? How about an office affair with a blond secretary?

First, we meet Cassandra, Amira’s predecessor who was summarily fired, probably at Beverly’s behest. Amira realizes that there’s another when Brock invites her to lunch and the blond server treats her with open hostility until Brock explains to the girl that Amira is just his legal assistant. Beverly phones Amira incessantly, tracking Brock’s whereabouts, obviously well aware of her husband’s proclivities. To thank Amira for keeping tabs on her husband, Beverly invites her to a dinner party at their home. There, Amira witnesses a social inversion, a taste of what is possible, where most of the guests are people of colour who lead interesting stimulating lives while the wait staff is white. As the end of the evening approaches, Amira sees a blond server take a glass of champagne. She moves to admonish the girl and recognizes her as the server from the restaurant. Thinking the girl is there to make a scene, Amira speaks rudely to her. Beverly steps in, handing the girl a hundred dollar bill and thanking her for babysitting the children; she has invited the girl knowing full well who she is so that she can spend the evening watching her husband squirm.

The collection’s final story, “Toronto, 2020,” takes us to yet another generic space, perhaps the ultimate in short-term rentals, a hospital. Jihan experiences acute abdominal pain and asks her father, a taxi driver, to take her to the hospital. (The hospital in question is North York General Hospital which, by coincidence, is where both my children were born.) A doctor in the emergency department diagnoses appendicitis and discharges her with a prescription for antibiotics. Omar describes Jihan’s interactions in the passive voice (“Her blood was taken. She was told to follow another nurse…”). Hers is an immigrant body, more acted upon than acting, with little agency in this space.

On her way out, Jihan thinks she sees Bilal Dire, someone she knows from high school who is two years younger. The problem is this: Bilal Dire was shot to death a few days earlier. Jihan went to the funeral. The whole community—a block of subsidized townhouses and apartments called the “Jungle”—mourned his death. Jihan inquires at the information desk, but they have no record of a patient by that name. Even so, she is certain it was Bilal Dire, so she returns to the hospital the next day and drifts unnoticed down corridors until she finds Bilal and verifies that it is in fact him. Yes, he was shot, and seriously injured, too, but he played dead even when the ambulance carted him away from the scene. Omar is deliberately vague about the mechanics of Bilal’s premature death. What is absolutely clear is that Bilal has no intention of resurrecting himself; he likes his indeterminate state and thinks he might take advantage of it to go “home”. Although born in Toronto, Bilal Dire regards Somalia as his home and hopes he might vanish into this unknown landscape.

What is going on here? We might take a clue from a curious paragraph in which Jihan shares the fact that, while riding to the hospital to visit Bilal, she reads Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth for school. She keeps skimming over a single passage: “Confronted with a world configured by the colonizer, the colonized subject is always presumed guilty. The colonized does not accept his guilt, but rather considers it a kind of curse.” Jihan and Bilal are “the colonized”. Again with the passive voice. Powers beyond their control hold them pinned in place, stuck in generic spaces, stuck in generic jobs. Only the accident of “death” offers a release from the curse, or at least a sideways drift into an indeterminacy.

Likewise, Idman Nur Omar leaves the reader afloat in a state of indeterminacy, unsure how to situate her characters in the world. For a reader like me—one of Frantz Fanon’s colonizers—this is an unfamiliar state. I’ve grown used to the idea of encountering the world in the active voice. Despite occasional anxieties, like those visited on all of us during the pandemic, it’s fair to say of myself that I feel at ease in the world. The ground lies firm beneath my feet. Even so, it’s important for me to recognize how contingent is this feeling, and I’m grateful for writers like Omar for the way they shake me from my complacency.

Visit the web site of Idman Nur Omar