I bought Grimmish at Word On The Street, recommended by one of the people manning the Coach House booth. Glad I followed the recommendation as the novel, by Michael Winkler, is well written, funny, with a self-deprecating humour that I found personally affecting.

The premise is straight-forward. Set in the early years of the 20th century, Joe Grim is an Italian boxer with mediocre technique, sloppy physique, and no defences, who routinely gets pommelled in the ring. However, he has one talent which sets him apart: he can take a beating. He has faced some of the biggest names in the business, and not even they can knock him out. They can knock him down, but before the referee reaches the ten count, Joe Grim is back on his feet, bloodied and dazed, but ready for his next beating.

Winkler shares an origin story, and although he laces his novel with newspaper clippings and footnotes to give it the air of pure reportage, the origin story betrays the novel’s affinity for tall tales and wild yarns, the sort of accounts that get shared in bars and grow taller and wilder with every telling. Joe Grim grew up in a small Italian village where the church stood at the centre of village life. His brother contracted polio and lost the use of his legs, so dragged himself around the cobblestone streets on his hands. Joe wanted to hire the local cobbler to make hand shoes so that it would be easier for his brother to drag himself around, but the family was poor and couldn’t afford such a luxury. To earn money, Joe stood at the steps to the church and called on passers-by to give him money. Once he had collected enough money, he would run head-first into the church’s great metal door and impress its cast religious scenes into his forehead. When this proved insufficient, Joe enlisted the help of a local giant to bind his arms and legs, turning him into a projectile, and the giant hurled him headlong into the door. This is how he discovered that he had a talent for absorbing pain, and what he learned at the church door, he took with him into the boxing ring.

Given Joe Grim’s role as a pain eater, and the religious scenes stamped into his skull, it’s a short leap to a messianic metaphor that treats him as a Christ figure. The story comes to us via the narrator’s uncle who was a hanger on and sometime cornerman for Joe. Of his first encounter, the uncle says “I want to see his body. Need to. Maybe put my hand in his side. Metaphorically.” A page later, when the fight is done, the uncle pulls off Joe’s boots and washes his feet. The narrator tells us of a play he wrote called Save Me, Joe Byrne. “The title was a borrow from the story of a young African-American man being put to death in a U.S. prison and as the poison gas entered the execution chamber they could hear him incanting over and over, ‘Save me, Joe Louis,’ and vulnerable young men I think have always hoped for a more powerful male to intercede in their fate at the last minute.” And more explicitly, we have a passage where the narrator wonders if Joe Grim could have born the pain of the crucifixion with more fortitude than Christ. You get the idea. There’s a redemptive quality to Joe Grim’s assumption of pain.

With all the messianic claptrap, you’d think a lamb would show up in the novel to complete the symbolism. But no. Winkler offers us a goat instead. During an extended tour of Australia (this is, after all, an Australian novel) where the uncle has attached himself like an acolyte to the suffering Grim, the pair find themselves riding a talking goat from Perth to Melbourne. To pass the time, the three of them—boxer, acolyte, and goat—share pig jokes. It turns out the goat has an absolutely filthy mouth, and the jokes are hilarious, all of which to remind us that we shouldn’t take the religious symbolism too seriously. Or any of it for that matter.

If there’s anything we should take seriously, maybe we should look away from the metaphoric connection between pain-eating boxing and redemptive blood sacrifice and turn, instead, to the metonymic connection between boxer and writer. Most writers (myself included) function like Joe Grim. We spill our ink like blood and never get any recognition for our craft, yet we can’t help ourselves. We keep bashing away at it. Taking the rejection. Eating the loneliness. Swallowing up the self doubt. There is something compelling about the craft that demands our devotion as much as any religious commitment. The narrator (or Winkler?) asks: “Could my unfulfilled writing career, replete with self-sabotage and a propensity for mock-heroic failure, be my own version of Grim’s pain pantomime? Exercising all the talent I have in something I love, falling always short of success (deliberately, at some level?), refusing to stop writing, convincing myself that I am trying my best and the pain of mediocrity is all part of the deal?”

The invocation of self-sabotage takes us to the question of mental health. The text is sprinkled with allusions to depression and migraine headaches (the narrator’s? the author’s? who knows?) and the story culminates in Joe Grim’s committal to an insane asylum. Joe howls and cannot communicate in any meaningful way. Eventually, the authorities release him, but he never returns to his old life. While people propose a number of theories for his breakdown, the theory that predominates is that Joe Grim isn’t as invulnerable to the beatings as his promoters would have us believe. The blows to the head may never have knocked him out, but they’ve definitely scrambled his grey matter.

Like the inimitable boxer, the writer may suffer a similar end, howling incomprehensibly while eating the psychic pain that fruitless writing engenders. Winkler leaves open the obvious question: is it worth it? However we answer it, the question is timely. The global pandemic has exposed the way in which so many of us are merely labour widgets in a vast late capitalist machine, utterly replaceable as we perform our meaningless work. So began the quiet quitting movement which is not so quiet anymore, especially as the rise of AI threatens great swaths of the labour market. Now, without the glimmer of a hope of a reward at the end of it, why bother trying? Maybe once, the prospect of a gold watch and an employer’s gratitude could sustain us. Or the idea of fulfillment through work. Or sense of purpose. But in today’s labour market, such thoughts are laughable. Work feels like bashing your head against a brick wall. Or a metal door.

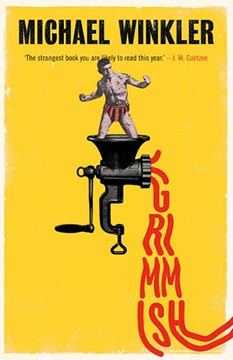

Maybe the fact of the book itself stands as Winkler’s definitive answer to the question: yes, keep bashing away at your keyboard and, one day, you too can see your book into print. And, one day, you too can persuade a Nobel laureate to endorse it. On the book’s cover, we have this comment from J. M. Coetzee: ‘The strangest book you are likely to read this year.’ Is that really an endorsement? Or is that more like a champion prize fighter giving a lesser known a backhanded smack across the jaw? Ah, but Winkler can take the pain.

Buy Grimmish from Coach House Press

Visit Michael Winkler online