This is a collection of short pieces—a follow-up act to Known and Strange Things—organized around the three pieces which form the Berlin Family Lectures. It’s natural, when reading a collection of disparate pieces, to seek for a sense of coherence, thematic threads that you can draw from cover to cover (apart from the obvious thread that all the pieces emanate from the author’s head and so, presumably, project to us something of his unique world view). My immediate response was to note what appears to me a concern for death, acknowledging death, railing against death, coming to terms with the fact of death. Death as portrayed in art. Death of migrants. Death as a fact of colonial violence. He bookends the collection with discussion of two mass shootings, one in Las Vegas, the other in Norway. It’s natural for me, as reader, to wonder what motivates this concern for death. Maybe, lurking in the background, lies the fact that, by training, Teju Cole is an art historian; maybe; lurking in the shadows, is some measure of guilt at the almost reflexive tendency to aestheticize traumatic events as a way to cope or even to explain them. As a photographer, this is a reflex I understand intimately. In his intellectual musings, Cole is too sophisticated to allow such an impulse to taint his thinking, and yet we can’t always control our impulses. Maybe he recognizes that he is subject to such an impulse, one that works at cross-purposes to his carefully articulated ethic, and maybe he responds to this recognition accordingly: guilt, disgust, self-castigation. But I speculate. His motivations remain obscured.

I’ve spent enough of my life reading—whether the pages of a book or the scenes that present to me through a viewfinder—to know that immediate responses are untrustworthy. I begin to suspect my initial assessment, that Cole’s latest book dwells especially on death, needs to be modified. Cole is less concerned with the fact and finality of death than he is with the liminal spaces that bound life. If he were a Roman Catholic, his theology would concern itself not with heaven nor with hell, but with purgatory. He is drawn to Caravaggio’s painting of Lazarus who, though he dies, cannot remain with the dead, prefiguring Christ’s own time in hell before his ascension. He is drawn to Caravaggio’s story, too, a man consigned to his own purgatory, forever fleeing the authorities after he commits murder. It is only a small associative leap to the contemporary liminal spaces marked out by refugees drowning off the coast of Italy or children in cages on the US/Mexico border or the contested boundary between Israel and Palestine. These are purgatories, too, and no one who takes seriously the idea that our interior life is necessarily a spiritual life can turn away from such matters.

I find confirmation of my modified view in Cole’s amusing account—the lightest moment in the entire book—of how his father returned to their home in Lagos with a door he had purchased in Brazil. At the time, his family didn’t own a home nor any land on which to build a home. For more than ten years, his father kept the door gathering dust in a back room, refusing offers of purchase, insisting that one day he would have a house for his door. Accompanying the account is a history of the door and of the word’s etymology. It turns out that the idea of the door, of the threshold, of the liminal space, the passaggio from one state to another, has been with us for a long time, perhaps for as long as humans have enjoyed the gift of articulate speech. Cole means for us to take this as a cue: in his writing, this is the space Cole marks out as his native ground. This is the space where he can luxuriate in his imaginative freedom.

Finally, a note about synaesthesia. In one of his pieces, Teju Cole explicitly addresses the synaesthetic experience, but the entire book (his entire written output, for that matter) demonstrates an affinity for a jumbled sensorium. He writes about his encounters with paintings and the affective dimension of visual experience. But he’s equally adept at locating the same affective dimension in his encounters with classical music. Odours evoke memories that transport him through space and time. Although the sense of taste tends to get short shrift, Cole nevertheless acknowledges its importance.

While we tend to think of synthaesthesia as a radical breach of the neat compartmentalization imposed on sensory experience, there are nevertheless ways in which each of us is a synaesthete. Reading itself serves as an illustration of this. For most of us, reading does not happen as a direct translation of visual experience (letters on a page) to pure meaning, but travels there via our auditory experience of language. In his Confessions, St. Augustine famously notes that his mentor, St. Ambrose, read silently. The passage implies that reading aloud was the norm and that silent reading was a relatively late development in the history of literacy. But even in silence, most of us “hear” the words we read as we navigate the passaggio from signifier to signified. The visual experience of letter on the page induces the auditory experience of words articulated in the mind’s ear.

For Cole, the idea of synaesthesia means something more than its clinical description suggests. Maybe it stands as a metaphor for something else, something deeply personal. Even for someone like me who does experience it in its clinical sense (ordinal linguistic personification), it offers up meanings beyond the bare description of the experience (e.g. the idea that each thing in the world—whether a rock, tree, flower or insect—might be a person with its own spiritual dimension). For Cole, its meaning might lie in the fact that it plays against the strict limits we impose on our invented categories. Cole is neither wholly Black nor wholly white, neither American nor African, neither solely an artist nor a writer, and so on through a great raft of oppositional dyads we have constructed to ensure we are forever divided both from ourselves and from each other. Synaesthesia offers a hope that maybe we aren’t naturally built to entertain such divisions after all. Maybe our most natural impulse is to tear down walls and to dissolve nice distinctions.

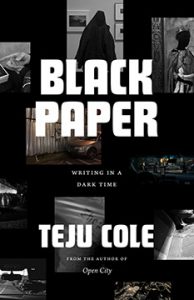

Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time, by Teju Cole (University of Chicago Press, 2021).

See also, Open City, by Teju Cole.

_______________

Image Credit: The Raising of Lazarus-Caravaggio (c.1609) (cropped) from Wikimedia Commons