This is a follow–up to my entry on BitTorrent. I have another theory about why BitTorrent doesn’t work. According to Wired, BitTorrent’s creator, Bram Cohen, has Asperger’s syndrome. People with AS have a neurological disorder which tends to impair their ability to function as social beings and can produce autistic–like behaviour. This may account for the fact that, although BitTorrent is a wonderfully efficient file transfer application, it falls flat in one seemingly innocuous respect which nevertheless may prove fatal.

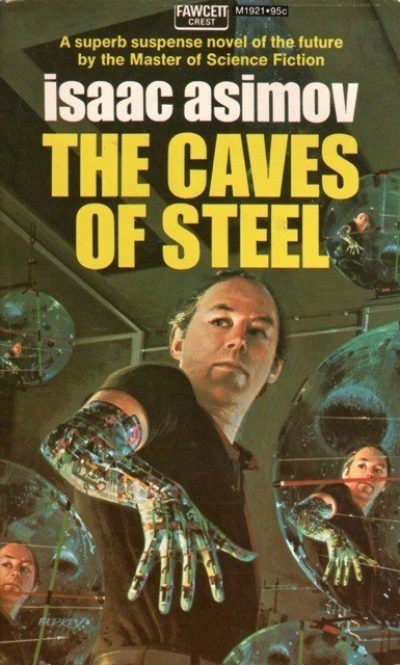

Let me explain by drawing an analogy to a science fiction story I read as a kid—Isaac Asimov’s novel The Cave’s of Steel. This is a futuristic detective novel. There has been a murder and the protagonist is assigned to the case. But there’s a catch. He has to work alongside a robot. It is understood that robots will replace humans in forensic investigations, and everybody assumes that it is the robot who will solve this particular murder. The protagonist is just tagging along to observe. As the novel progresses, the tension mounts between man and machine. But late in the investigation, as the human reviews the crime scene, he notices something which proves to be the vital piece of evidence—the damning clue. What’s more, he realizes that the robot could never have recognized the evidence as a clue. I won’t reveal the clue. However, I will reveal the point. The clue is left behind because of the murderer’s idiosyncratic and all-too-human foibles. And it is only those who have access to such foibles who can identify the trail they leave. Robots have no access to the emotional impulses that direct human behaviour, and so they cannot perceive the relatedness of seemingly disconnected elements.

Bram Cohen reminds me a little bit of the robot in The Caves of Steel. His program has a kind of purity, a kind of elegance, for the counterintuitive result it produces—the more people who request a file, the faster they can download it. It reorganizes the perverse incentives that prevent us from gaining the optimal results that can be achieved through co-operative behaviour. And yet, as I point out in my earlier entry on BitTorrent, it makes an invalid assumption. It assumes that everyone is in agreement as to what constitutes selfish behaviour. And it assumes that everyone wants to participate in the first instance. However—and this is Asimov’s point—humans are never rational self-interested actors. They love. They hate. They feel things passionately. They form allegiances. They spout their protestations. And they cry.

Any algorithm which seeks to reorganize perverse incentives implicitly makes two claims: (1) that it has an accurate picture of such perverse incentives; and (2) that it has an accurate picture of the results which reordered (“efficient”) incentives ought to produce. I defy anyone, much less someone with AS, to write code that offers even a pale approximation of how (badly) humans make their decisions.