My sister-in-law called with a grammatical question. A family argument had arisen. They wanted to know the correct use of the comparative. Here are the options:

1. He is bigger than me.

2. He is bigger than I.

My brother and my nephew insisted that the correct usage is #2. My sister-in-law, who is bilingual, worked from analogy to the French language where the preposition would take the accusative case. Therefore, the correct usage is #1. My niece, perhaps the most sensible of all, held no opinion on the matter.

At first, I felt honoured to be considered the competent adjudicator of family disputes, but given the subject of the dispute, I begin to doubt my elevated position. My response was immediate, and I based it upon Latin grammar: the comparative takes the accusative case, the object, as its noun—”me,” not “I.”

But, because I am as pathetic a dweeb as my brother, I woke up in the middle of the night with my head full of grammatical insight—there was a plausible justification for the other choice. Both could be regarded as correct. There could be an implied copulative verb. Ahhh. The implied copulative. He is bigger than I (am). I got on the phone and called my sister-in-law to caution her against deriding my brother for his poor grammar.

I began to reflect. I wondered how it is we choose. There seems to be a nuance here which remains silent, the slow creep of linguistic development that lurks just below the threshold of our collective awareness. In the case of the comparative, there is a distinction between “high” and “low.” “He is bigger than I” implies a well-educated or more refined speaker. “He is bigger than me” implies a casual sloppiness. It is not boorish, but neither is it elegant.

The same distinction between high and low speech has inveigled itself into another prepositional usage—where it is used in conjunction with a conjunction. The rule is that a sentence should never end with a preposition. But, in everyday usage, most people always place the subordinate clause first and end the sentence with the preposition. They prefer “the place I ran to” over the technically correct “the place to which I ran.” The former, with its dangling preposition, can be justified on the same logic as the implied copulative verb; in this instance, there is an implied repetition of the object: “My house is the place I run to (my house).” The dangling preposition is justifiable. It is not boorish, but neither is it elegant.

What are the “rules” of grammar? Some would argue that they define proper language. Others, most notably linguists, would generally argue that the “rules” merely describe what is already happening when people communicate. They are not prescriptive, like laws. What “feels” right defines correctness in speech, and the “rules” merely follow upon our intuitions about the nuance of our living speech.

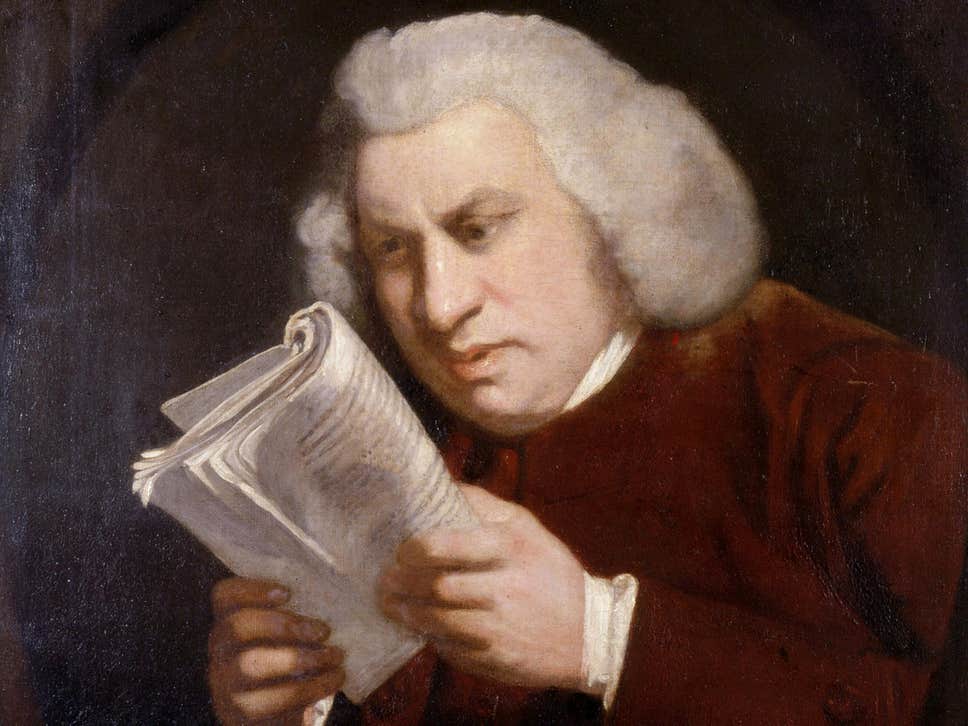

We see the same thing happening with dictionaries. Early lexicographers, like Samuel Johnson, were merely record—keepers, documenting an already extant vocabulary. But at some point, lexicographers came to entrench vocabulary: if it wasn’t in the dictionary, then it wasn’t a “real” word—so claims Scrabble in its rules of play. Compounding the grammatical entrenchment wrought by dictionaries is the sludgelike flow of linguistic development induced by style books like those prescribed to students at institutions of higher learning and like those used in-house by publishers. However, people invent new words and new usages every day. Corporations create brand names which pass easily into popular usage and we xerox our documents. Song writers invent words for our amusement and we sing supercalifragilisticexpealidocious or bootylicious. New technologies give rise to new activities which demand the creation of new words and so we email one another or google a word. And sometimes a word seems to emerge all on its own from a mysterious primordial linguistic soup and we say that something is ginormous.

Maybe there is no right nor wrong to words. Maybe there are no rules except those we choose to impose upon ourselves. Maybe our words form a social process which, like a river, keeps flowing whether we swim against the current or allow ourselves to be carried along (the river).