For my wife’s birthday, I bought her tickets to Wicked, which we saw on Saturday. It uses the Wizard of Oz as its point of departure and tells the story of life before Dorothy—the relationship of Glinda the Good Witch and Elphaba (who became the Wicked Witch of the West)—and also the story of how the Scarecrow, Tin Man, and Cowardly Lion came to be. I must say that the lead, Stephanie J. Block, has a tremendous set of pipes and is very strong. I hope she returns to Toronto soon.

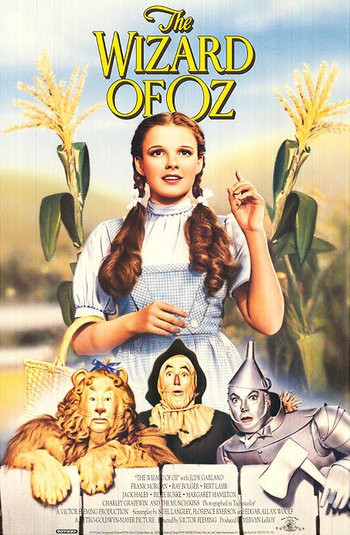

The musical presumes a certain knowledge of the Wizard of Oz, a reasonably safe presumption given that the Wizard of Oz is one of the cultural icons of the 20th century. Everybody quotes it. “I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore, Toto.” “There”s no place like home.” “If I only had a brain.” And everybody can hum a few bars or sing a few lines from “Over the rainbow.” Can’t they? I thought so—until a few months ago during a class on Lonerganian epistemology.

Say what?

In one of the first classes, we were reviewing Platonic epistemology. We were talking about the idea of eternal forms, transmigration of the souls, knowledge of the self as a kind of recollecting of whom it is we already are, etc. The professor thought he was being helpful by offering an illustration. “It’s like the Wizard of Oz,” he said. “There are these three dudes”—it would be a mistake to think that philosophy or theology professors talk with big words all the time—”the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, & the Cowardly Lion, and they all want something from the Wizard, a brain, a heart, and courage. But when they finally get to meet the Wizard, they find out that he’s a fake. He can’t give them any of these things. But he does have one insight he can give them. He tells them that if they look inside themselves, they’ll find that they already have the things they were looking for. So you see, the Wizard is a Platonist.”

When the professor had finished with his illustration, 3 of the students stared at him like he was from Mars. There were 7 students in the class. The professor and I are local boys, both born and raised in Toronto. Another is relatively local—from Peterborough. Two others, one from upstate New York and the other from the U.K., were well acquainted with the Wizard of Oz. But the other 3, one from Germany and the other 2 from France, knew nothing about the musical. The professor was surprised—and maybe a little annoyed that he had to think of another illustration.

We in (North) America tend to assume that what we take to be culturally iconic is likewise for the rest of the world. And what could be more culturally iconic than the Wizard of Oz? After all, didn’t the American Film Institute name it #6 of the top 100 films of all time? In point of fact, the Wizard of Oz means nothing to most of continental Europe, and even less to Bollywood, China, southeast Asia and South America. In point of fact, the Wizard of Oz is iconic to only about 5 percent of the world, which means that, in point of fact, the Wizard of Oz is not culturally iconic at all.