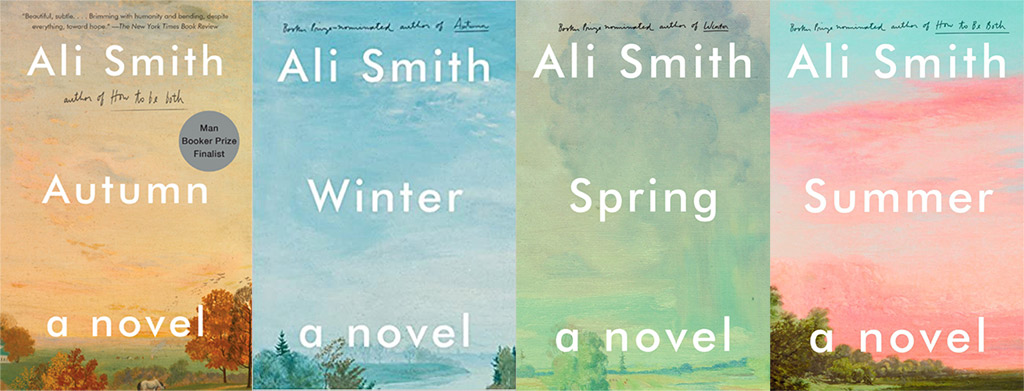

With her seasonal quartet, Ali Smith has the distinction of writing one of the first novels that places its characters squarely in the context of Brexit (Autumn) and one of the first novels that places its characters squarely in the context of Covid-19 (Summer). This tetralogy is a remarkable achievement, offering a clear-eyed view of the times without resorting to the usual maudlin emotions—outrage, disbelief. Instead, through her wise art, she offers us reassurance.

What follows is not a synthesis of all four novels. Instead, I have reproduced the impressions I recorded after reading each. You’ll note that the first two are in the wrong order. That’s how I read them. I don’t think it matters.

Winter

Apparently this is part of a tetralogy, each volume titled according to a season. However, I didn’t know what season Ali Smith started with so, Covid-19 protocols being what they are, I took down the first book my fingers touched—Winter—which turns out to be the second instalment. I read it anyways and find that it stands on its own. I have no idea what Autumn is about or whether it even matters to my appreciation of Winter. That fact itself may be important to appreciating Ali Smith’s work or at least a certain aspect of her work: the treatment of time.

I will need to listen again to her 2014 interview with Eleanor Wachtel in which she discusses some thoughts she has about the nature and importance of time. I was riding an exercise bicycle while listening to the interview so I’m not sure I gave it its due what with all my huffing and puffing. Still, when one thinks of the seasons, one tends to think of them following a fixed progression, cyclical yes (like my exercise bicycle), but in one direction only. A more sophisticated version of this might analogize to climbing a spiral staircase, returning again and again to the position but always advancing upwards. But time seems freer for Ali Smith. Certainly freer within the novel where characters move simultaneously in present times and remembered pasts (as do we all). So why not with the tetralogy? Does it matter whether you start with Winter or Summer, or whether you read them in accordance with their natural progression? I will have to decide later.

So we have Art (see also Ali Smith’s interview comment about how she would like to chop up the Lord’s Prayer and use each bit as its own book title e.g. Art In Heaven). Art’s partner is Charlotte who has left him. She is a presence who never makes an appearance in the novel. Art has promised to visit his mother, Sophie, but Sophie is expecting to meet Charlotte. Art sees a young woman in a bus shelter and offers her £1,000 to pose as Charlotte for a long weekend. Lux, the girl he has hired, takes to the role with more gravity than Art had expected, even turning the screws to get Art to invite Iris (Sophie’s older and mildly estranged sister) to join them. The only other bit of plot is that Charlotte has taken over Art’s social media accounts and makes occasional exaggerated posts in his name including the sighting of a Canada warbler on the coast of Cornwall. As a result, a busload of birders interrupts their weekend as they hunt for the stray Canada warbler.

As far as plot goes, that’s about all there is. Ali Smith seems a tad unconcerned with the usual conventions like plot and Aristotelian unities. She concerns herself more with time (as mentioned above), what it means to be human, and paying attention to things that have fallen out of favour in today’s current global cultural context, things like ambiguity, subtlety, liminal spaces, and quiet gradations.

Autumn

At last I have found which book comes first in Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet. I don’t suppose it matters since the elements of one are not dependent upon what has gone before nor, I suspect, do they provide a foundation for what follows. I was looking to recall the surnames of the characters and resorted to Wikipedia and found that the Autumn entry included a subheading called “Plot.” Maybe all Wikipedia novel entries are required to include a subheading called “Plot.” Any other possibility would force me to conclude that whoever authored this entry is stupid.

Ali Smith doesn’t deal in plot. To the extent that any of her novels have a plot, it is something the reader constructs from inferences strewn here and there to satisfy the reader’s need for a mental crutch. Plot is a way to organize time. But plot isn’t the only way we can organize time. We also have memories and dreams which are associative and therefore sometimes engage us in wild leaps.

In Autumn, there is an oppressive now. I say oppressive because it is set in post-Brexit Britain where consciousness is dominated by a bitter and divisive public conversation. Set against the oppressive now is a liberative past which has all but vanished from memory. This is the past of Pauline Boty, Britain’s first and perhaps only Pop Artist, who died of cancer at the age of 28 in 1966. To that point, she had lived large, accepting commissions for collages, showing a young Bob Dylan around London, making an appearance in Alfie as one of Michael Caine’s exploits. She is regarded as a herald of second wave feminism, an icon of joyful sexuality, a thinking woman’s Brigitte Bardot.

Mediating between these two times are the two principal characters, one young, one old. The prepubescent Elisabeth Demand meets her new neighbour, Daniel Gluck, an elderly gentleman. They begin to spend a lot of time together, going for walks, watching films. Elisabeth’s mother is wary of the burgeoning friendship but rationalizes it on the (possibly erroneous) belief that Daniel Gluck is gay. In the end, it doesn’t matter. The friendship is just about the only source of nurture and respect in Elisabeth’s life.

One of the things Daniel does is describe images. These are works of art he believes no longer exist and so describing them is the only way he can share with other people the joy they have given him. Once again, we join Ali Smith in her ongoing exploration of the complicated relationship between text and image. In the case of Daniel Gluck, the act of describing art serves the same function as memory. It calls to mind a statement by John Berger in his essay on the “Uses of Photography” in About Looking:

Memory implies a certain act of redemption. What is remembered has been saved from nothingness. What is forgotten has been abandoned. If all events are seen, instantaneously, outside time, by a supernatural eye, the distinction between remembering and forgetting is transformed into an act of judgment, into the rendering of justice …

There is a hint that Daniel was once in love with Pauline Boty. But that is lost, as are her collages and other creations. All that remains of them in the world are his memories which he passes along to Elisabeth. Inspired in large part by Daniel, Elisabeth goes on to study art history and stumbles upon photographs which she recognizes from Daniel’s descriptions. It turns out Boty’s works were not lost after all. The story goes—and you can verify this on Boty’s Wikipedia entry so it must be true—that they were stored in a barn on her brother’s property where they were forgotten for almost 30 years. Elisabeth does a dissertation on Boty’s life and work.

Returning to the oppressive now, it is worth inquiring whether the way we inscribe it upon our memory, for example through the writing of novels, is a quiet call to justice. Right wing leaders who tend to isolationism and, potentially, Fascism—Brexit, Trumpism, Bolsonaro, Modi—are only possible with a collective forgetting. Acts of remembering are a form of resistance.

Spring

I’ve started to think of Ali Smith’s quartet as a tapestry which, when we are able to step back and view as a whole, presents to us an image of our times, not a slavish representation, more a spiritual reckoning. In Spring, Smith weaves fresh strands into the cloth and, in at least one instance, ties off something from an earlier novel. That said, once again, I underscore that this novel can stand on its own. It is not diminished for reading in isolation, but enriched for reading with the others.

Spring is the 3rd novel of Smith’s seasonal quartet and opens, funnily enough, in the autumn of 2018 “on a train platform somewhere in the north of Scotland.” Richard Lease is an aging television and film director who has just lost a dear friend, colleague and, on a single occasion, lover, Patricia (Paddy) Heal. He had recently consulted her, more like sought moral support, because he has agreed to film a piece produced and written by a youngish upstart named Martin Terp. The premise is appealing, but Terp’s adaptation is crass and now Richard regrets ever getting involved. He looks to Paddy for sanity and sage advice, but now she is gone.

The premise of the film is simple. In 1922, infected with tuberculosis, Katherine Mansfield went to a hotel in a small Swiss village in order to convalesce but really to die. At the same time, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke was checked into the same hotel, a much older man, dying of leukaemia. Neither would ever know that the other was a guest at the hotel. Terp, however, suffers from the affliction of our age and has taken liberties with the facts.

The proposed scene which particularly irks Richard has the dying pair trapped together in a stalled cable car. Inevitably, they find themselves twined in a passionate embrace while Mansfield’s husband looks on, trapped in an adjacent cable car. As Smith does so adroitly in other situations, she leverages this scenario to produce what might be called sympathetic temporal vibrations. Simultaneously, we can imagine the Mansifeld/Rilke non-encounter of 1922 (incidentally, the book cover is a detail from a 1922 painting by Boris Michaylovich Kustodiev), the Richard/Paddy relationship of the 70’s and 80’s, and Richard’s current hand-wringing over a ludicrous film script.

Despite the comedic set-up, the situation presents a darker possibility. Richard climbs off the platform and positions himself beneath a stopped train, thinking he might end his life by letting the train roll over him. A twelve year old girl interrupts his haphazard plans by calling to him in a preternaturally mature voice: I really need you not to do that.

A second thread of the tapestry involves Brittany Hall who works for the SA4A as a CDO of the IRC. I’m not from the UK so I have no idea what these acronyms stand for but it is enough to know that Brittany Hall works at a detention facility where the British government warehouses immigrants and refugees for indeterminate terms in prison-like conditions. Although there have been intimations of a detention facility lurking in preceding novels, this is the first time we’ve had a look inside such a facility. All the employees, including Brittany Hall, carry themselves with a fair degree of certainty, or at least the kind of certainty that settles over one’s thoughts when one doesn’t bother to interrogate one’s self too closely. I would hazard to guess this is the condition most of us find ourselves in regarding most everything we do. In Brittany Hall, Ali Smith doesn’t offer up a loathsome being; on the contrary, she is likeable; but she is blinkered all the same.

The only hint of disorder in Brit’s mechanized work life is the rumour from other detention centres of a young girl who passes undetected through security check points and wreaks all sorts of havoc, like persuading authorities to give detention centre toilets a proper cleaning. Part social satire, part magic realism, Smith’s story slyly evades easy categories.

On the way to work one day, Brit encounters the girl, Florence (like the city or the machine) and suspects that this might be the girl of workplace rumours. Brit tails the girl, amazed at her Jedi-like ability to render herself invisible to figures of authority like ticket collectors on trains and hotel receptionists. Together, they ride a train from London to the Scottish Highlands where the girl finds a man lying down in front of the train, trying to kill himself. Here, Smith weaves together two threads and carries on from there with a brief road trip: all this time, Florence has been aiming to discover the site depicted on an old postcard she carries with her.

Smith weaves in another thread when we learn that Richard Lease is the estranged father of Elisabeth Demand, the young art historian we met in the first novel, Autumn. Although the 4th volume might prove me wrong, this coincidence strikes me less as a novelistic contrivance than as precisely what it purports to be: a coincidence. It feels satisfying in that it makes me, as a reader, sit up at attention and say to myself: Oh, now, isn’t that interesting. Yes, it contributes to the larger work’s sense of structure (the tapestry), but it’s not clear to me yet that it means anything.

I have an answer to this conundrum, but it’s convoluted. It begins with an exchange between Richard and Paddy shortly before Paddy dies. Richard mentions a computer game, a ship and a torpedo. Paddy says:

You have to applaud [human ingenuity], finding such interesting new ways to enjoy the destroying of things. How’re you doing, apart from the end of liberal capitalist democracy?

The association of destruction and liberal capitalist democracy sounds like it could have come straight from Hannah Arendt: “The most radical and the only secure form of possession is destruction, for only what we have destroyed is safely and forever ours.” One form of possession, whether in a novel or IRL (in real life), manifests itself in the impulse to impose meaning upon experience. We colonize our comings and goings, just as we colonize our paragraphs, by demanding that they bear significance. I, as a reader, insist that an apparent coincidence draw me to a deeper understanding. Gratuitousness in art is intolerable; we get our fill of it in life and, even then, we rail against it. Raised as we are in the shadow of Chekov’s rifle, we go bonkers at the appearance of a stray fact, a digression, a drift into playful irrelevance.

This fetish with semiotic utilitarianism seems to have climbed from the same slimy pool as Paddy’s liberal capitalist democracy. It’s encoded with the same primitive DNA. It wants to possess, consume, devour, and ultimately destroy whatever it coaxes into its lazy maw. I would like to think Ali Smith resists the overwhelming force of a culture that demands sense from random the same way it demands a plan from Boris Johnson or coherence from Donald Trump. There are no subtle threads woven into a better future. Only frayed strings scattered across the floor. I hope the 4th novel doesn’t prove me wrong by drawing all these different story lines into a neat well-contained conclusion.

Summer

While reading my way through Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet, I have made a point of writing about one volume before moving on to the next, capturing my impressions along the way rather than formulating a grand picture of the whole. Proceeding this way, I risk the possibility of embarrassing myself should something appear in a subsequent volume that shows me up as wide of the mark. Or not. In fact, I’m feeling smugly satisfied with myself that I concluded my impressions of the 3rd volume, Spring, with mention of both Hannah Arendt and the role of coincidence in art. Both appear in the opening of Summer.

First we have an argument between a teenaged girl, Sacha Greenlaw, and her mother, Grace, about a quotation Sacha is using in a school assignment. The quotation is this: “Forgiveness is the only way to reverse the irreversible flow of history.” She attributes it to Hannah Arendt on the internet. Her mother cannot believe that a school would accept such an attribution. If you Google the quote, you will discover that it is impossible, using the internet, to identify a primary source for Arendt’s statement. Funnily enough, since its publication in August, Smith’s novel is listed on Google as yet another source for the quotation, illustrating how easily digital culture rips profound sentiments from their context.

Sacha avoids further confrontation with her mother by going to the nearby beach where she thinks about the very things we all thought about early in 2020: wearing masks, pangolins, viral infections, racial tropes. Yes, Summer is among the first novels published that explicitly addresses Covid-19 and the global pandemic. From Covid anxieties, Sacha’s mind leaps to an earlier evening on the beach when she looked at a building and saw cleaners working in it even though it was past eleven at night:

It felt like she was meant to see it.

But it also didn’t mean anything. It was just coincidence.

Maybe coincidence never means the way you want it to. Because if it did it wouldn’t be coincidence, would it?

The two concerns I raise in reference to Spring—Hannah Arendt and coincidence—appear in the opening of Summer. What can be more gratifying than to have my reading confirmed by the author herself?

On cue, we have a coincidence with all the philosophical questions it imports. Sacha’s younger brother, Robert, appears on the beach. Robert is a fourteen year old surly stewing pot of anti-social hormones. He pulls a prank on his sister, enticing her to grip a super-glued egg timer (time on her hands). The glass cracks and cuts Sacha’s hand. Who should come to the rescue but Art and Charlotte. We met Art—Art In Nature; Art In Heaven—back in Winter when he paid a girl named Lux to pose as the estranged Charlotte on a visit to his mother. We have not met Charlotte before. She is young and beautiful and Robert is smitten by her, utterly mortified that he has been so immature.

We share with Robert a question about Charlotte’s status: is she or isn’t she with Art. As with so many things, the answer is: it’s complicated. They are no longer a couple, but they are no longer estranged either. This is much like Sacha’s and Robert’s parents, who are divorced but have chosen to live in adjacent halves of a duplex even as their father has started to live with a younger woman. We must pay attention. To loss and return. To betrayal and forgiveness. To irrational connections that sustain us despite our best efforts to keep ourselves separate. These personal dramas have their correlates in the wider political sphere.

Charlotte and Art are on a quest of sorts, and they invite the Greenlaw children and their mother, Grace, to join them. Art has discovered amongst his late mother’s possessions a part of a Barbara Hepworth sculpture which appears to have been stolen from its rightful owner during a sexual indiscretion. Barbara Hepworth’s work is reminiscent of Henry Moore’s abstract forms (I say this for the benefit of my readers in Toronto where Moore’s work is on prominent display.) The piece imagined here is a “child”, a polished stone orb that belongs with its “mother”, another polished stone form with a hole through its middle. Charlotte and Art want to unite child with mother by returning the child to its rightful owner, Daniel Gluck, the elderly man whom we met in Autumn. Again, coincidence tempts us to ascribe meaning to circumstances which may or may not warrant it.

But here, a different kind of coincidence appears, where a character’s experience leaps off the page and into my personal world. In Summer, we learn more about Daniel Gluck. We learn that he was born in 1915. That he is approaching his 105th birthday. That, as a young man of German descent during World War II, he was deemed an undesirable alien and interned on the Isle of Man. For me, 2020 opened with a gathering of my wife’s family, including its matriarch, Umeko, also born in 1915, also deemed an undesirable alien during World War II, and interned, in her case, as a Japanese Canadian in the interior of British Columbia.

We hold up these blots on our history because, looking back nearly 80 years after the fact, the underlying racism, nationalistic jingoism, and economic isolationism are easy to name for what they are. The same tendencies have arisen again, and our unwillingness today to name them for what they are is possible only with a deliberate historical amnesia. Art nurtures our memory and it serves a prophetic role, too, pricking our conscience.

Ali Smith’s novels are multi-dimensional, vibrating alongside historical interactions, as we’ve seen before with Pauline Boty in Autumn, Barbara Hepworth in Winter, Katherine Mansfield and Rainer Maria Rilke in Spring, and, in Summer, the Italian film director, Lorenza Mazzetti. But they vibrate along another axis, too, drawing sympathetic waves from writing that has gone before, most notably here, The Winter’s Tale. Grace recalls how, as a young woman, she had spent a summer working with a theatre troupe and one of the plays they staged was The Winter’s Tale. She played understudy to Hermione, killed by her jealous husband in the first act and miraculously warmed to life from a statue in the last act. After a disastrous performance—Grace was miscued and ended up walking onto the stage when she was supposed to be an immobile statue—the troupe argues about the point of the play:

The argument is the same one they keep having. It is getting tiresome. It’s about why Leontes in The Winter’s Tale wigs out quite soon after the start of the play.

The argument is about feminism. Again.

Grace sighs.

But it’s not about gender, she says. It’s just a blight. A blight comes down on him, on his mind and on his country from nowhere. It’s irrational. It has no source. It just happens. Like things do, they just suddenly change, and it’s to teach us that everything is fragile and that what happiness we think we’ve got and imagine will be forever ours can be taken away from us in the blink of an eye.

Grace is only half right. While we must acknowledge the contingent in our lives, it is not so that we might cower in fear. After all, this novel is Summer and, like the statue of Hermione, it warms to life. It’s a novel that presides over reconciliation, return, and forgiveness. With the help of social media, contemporary politics creates the impression that only our basest impulses have any currency today, but Ali Smith is here to assure us that such impulses are not the last word.