Québécois author, Patrick Senécal‘s 2010 novel, Contre Dieu, has been translated by Susan Ouriou and Christelle Morelli and published in English by Quattro Books as Against God (2012). It could be described as a novel about theodicy in the 21st century or The Book of Job on amphetamines. Like Job, this is the story of a man who loses everything while God (who doubles as the narrator) looks on, impassive. One evening, his wife is driving home with their two young children when she loses control of the car on a tight turn and all three are killed. When he learns of their deaths, he asks his friend repeatedly: Where’d I go wrong? And to his brother-in-law: But I did the same as you. Not the same job, that’s true: you studied and all that, me I’ve got no education, but I worked hard, I opened my store, I succeeded. I did what I had to do, just as much as you … These are the classic questions that ground theodicy: if God is all-loving and all-powerful, why does He let bad things happen to good people?

At the funeral home, people offer the usual platitudes. Take his cousin, Juliette, who is wheelchair-bound. She tells him: everything happens for a reason … He accompanies her outside for a smoke and asks if the accident that left her in a wheelchair happened for a reason. She insists she’s stronger for it. He lets the wheelchair roll down the ramp and into traffic. A car screeches to a halt and the one behind rear ends it. He asks his shaken cousin if she feels stronger now.

Things roll downhill from there. What follows is a drunken rampage that culminates in murder, arson and rape. In a confrontation with a priest, he describes himself as an instrument of chaos. The priest responds: No, you are not the instrument of chaos. You create chaos. There is a huge difference.

The difference, it would seem, is that if he were an instrument of chaos, there would be an intentionality behind his actions. But Senécal is careful to present each act of violence without a hint of intentionality. Things simply happen. And we sit apart, godlike, and witness their happening. What is against God is not evil. In Job, or in Paradise Lost, Satan is evil because he intends his actions to produce evil consequences. In a way, Satan’s evil is simply God’s good from a different point of view. Maybe what is truly against God is action with an utter absence of intention. Pure chaos.

The Wikipedia entry for Patrick Senécal states: “Certains critiques le voient comme le Stephen King québécois.” This is reiterated in a Quill and Quire article [dead link]. I think they’re wrong. Senécal writes better than that. Against God is written as a single run-on sentence which creates the effect of a headlong rush into the chaotic heart of loss. It is harsh and uncompromising in the way it challenges our moral assumptions.

Here’s a sample of the writing, another random act of chaos:

the train stops in front of you, you step inside, remain standing, holding onto the centre pole with your right hand, the train rocks its way through the tunnel, a couple sits across from you, a baby stroller in front of them, an old woman sits farther up, the young couple murmurs sweet nothings, the young couple smiles, the young couple kisses, the young couple is alone in the world, as for you, you eye them witheringly, and you turn to look at the stroller, and you see the sleeping baby, and you turn back to the couple, to their smiles, to their cooing, to their kissing, then the train stops, the doors open, no one stands to leave, the couple still lost in loverland, the couple oblivious to one and all, you give the stroller a push then, quick but firm, and the stroller rolls outside a second before the doors close

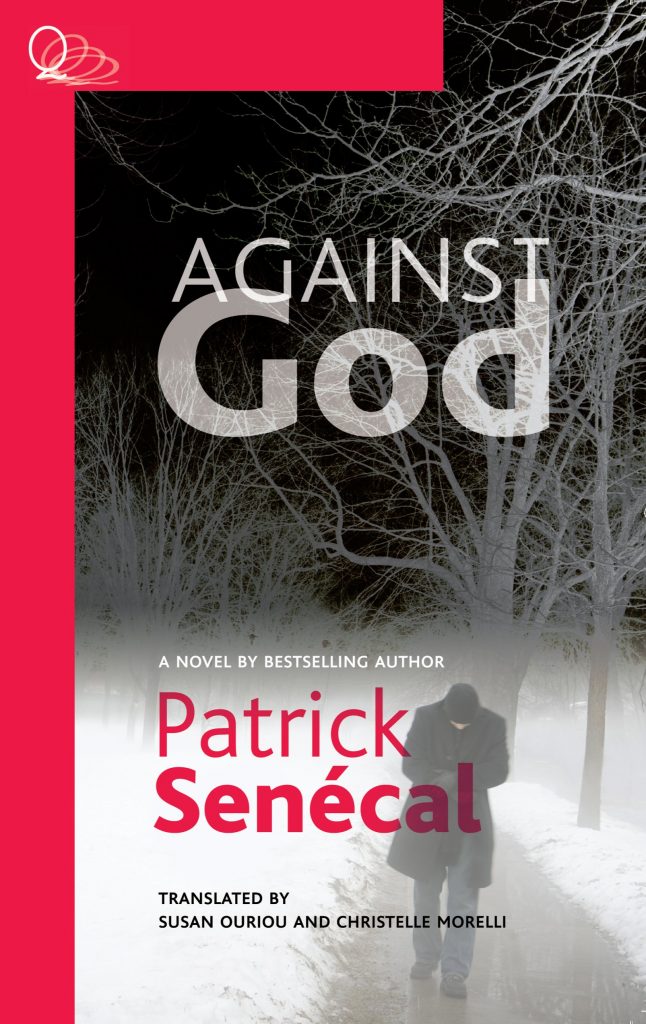

This scene is featured in the book trailer: