There is an apocryphal story about Einstein that goes something like this:

One day, Einstein was standing at a counter while a civil servant completed a form for him. The person asked for his telephone number but he couldn’t remember it. The person was incredulous that a man of Einstein’s genius and reputation was unable to remember his own telephone number. But, as Einstein explained, why should he clutter his mind with information that he could look up in a book?

I don’t know if the story is true, but it has in it an important truth.

In recent years, here in Ontario, successive conservative governments have subjected the public education system to a comprehensive overhaul. They have implemented a standard curriculum, and they have introduced province–wide testing. This is symptomatic of a more general shift in the mood of the country, the continent, the times, a yearning, if you will, for a simpler time when everyone learned the basics and all children were dutiful and polite. Now, our youth are going to hell—as they have been doing for nearly 2,500 years if we are to believe Aristotle. Or are they?

There is no question that the conservative agenda is working. And it has the test results as proof! The conservative method of demanding change, then creating an “independent” organ to measure it, reminds me a little of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, two court dandies so preoccupied with flattering one another that they were oblivious to the fact that Hamlet had sent them to their doom.

The failure of the conservative government was this: it had no idea what constitutes a good education; it had no idea what we should be promoting as intelligence; and it certainly articulated no clear idea how (or why) it planned to harness intelligence as a positive social force. And while it is most likely the case that intelligence cannot be taught, we nevertheless have a duty to promote environments which allow it to flourish, and we have a stronger duty to prevent those circumstances which are a hindrance to its nurture.

Here is another story to illustrate the nature of intelligence, or rather, the absence of intelligence:

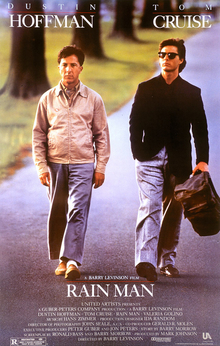

In the film, Rainman, Charlie Babbitt (played by Tom Cruise) finds himself on a road trip with his older brother, Raymond (play by Dustin Hoffman). Raymond is a high–functioning autistic (what once was known as an idiot savant). One scene is set in a diner. Charlie asks the waitress for her name, and when she gives it, Raymond spontaneously spits out her telephone number. The night before, he had sat in bed with a flashlight and memorized half of the local telephone directory.

On one view of it, this is an amazing feat. But on another view, it is a tragedy. He can fill his head with reams of useless facts, but he can scarcely give expression to the things which are fundamental to his humanity. Yet it is precisely this devotion to useless information that our politicians (and us, through our votes) valorize.

This is not intelligence. This is not education. We have machines to do these tasks for us. Sometimes, I hear older folks (even people younger than me!) bemoaning the fact that kids today are allowed to use calculators in math class. “Why, when I was a kid, we had to memorize our times tables.” They make it sound precisely like the drudgery it was. So why would they want to inflict such drudgery on their children and grandchildren?

I have a different perception of what constitutes a good education. For me, education is the perpetuation of a burning desire to discover—and to engage—the world I inhabit. Education is about method, not content.

I remember my first term in law school. It was one of the most disorienting times in my life. In retrospect, I understand why it was so disorienting. For the first time in my life, I was forced to think—to truly think—for myself. I was forced to examine everything with a critical eye. Inevitably, there comes a day in a law student’s life when someone, a family member or a friend, asks what the law says about trespass or noisy neighbours or some other inconvenience of modern living. And inevitably, the law student feels squeamish, afraid to admit ignorance. And yet it is ignorance which is the law school’s virtue. Any one of a thousand drones can go to a librarian and ask for the latest statutes or case law. But that has nothing to do with a legal training. The law is always changing. In a few weeks, today’s statutes will be run through the shredder. A true lawyer is someone who possesses a critical mind, someone who can apply critical faculties to any problem, someone who can devour whole disciplines in a weekend, someone who always holds in reserve the capacity to understand absolutely anything, but only when needed. Don’t expect me to know what the law is; only expect that if you ask me, I will find it out. And when I do, then you will know that I am an intelligent man.