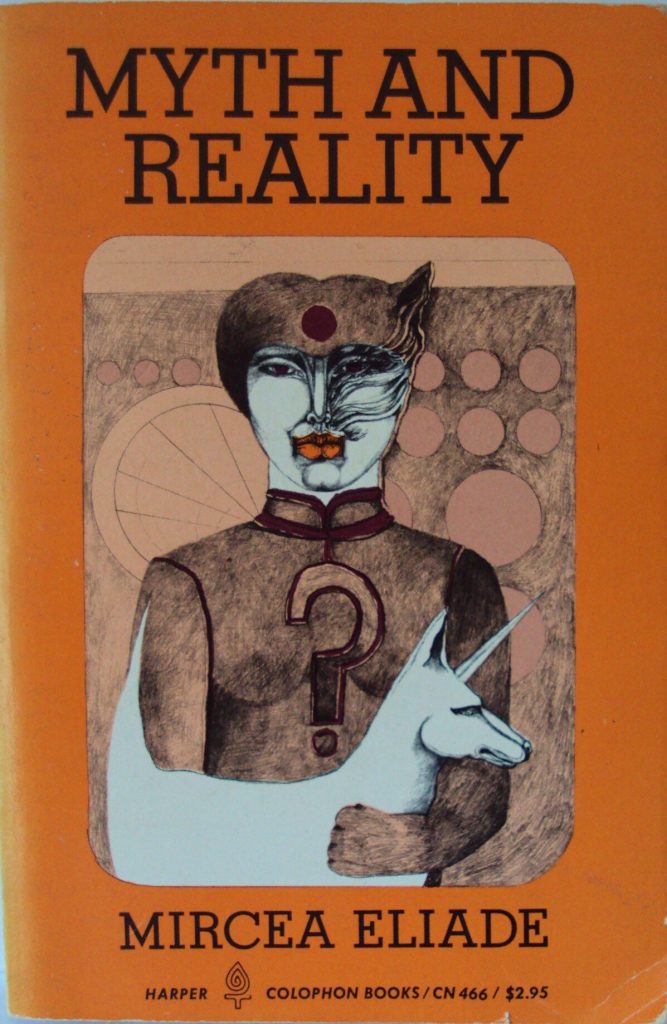

Fifty years ago, Mircea Eliade published Myth and Reality in which he explored the function of myth in a wide-ranging sample of cultures and religious contexts. His writing cut across the traditionally established boundaries that divide a number of disciplines: anthropology, history, religious studies, cultural studies. The writing is distinctively modern in that it has a universalist flavour. He rarely uses the pronoun “I”, but prefers the more impersonal “One” or the royal “We”. So we end up with sentences like this: “To repeat: we have no intention of putting Indo-Chinese mystical techniques and primitive therapies on the same plane.” Statements appear with authority. Every phenomenon has an explanation, and Eliade is going to reveal that explanation for our enlightenment. He interprets “primitive” (always in quotation marks) cosmogonies by subsuming them (swallowing them?) within the wider cosmogony—the modern perspective.

We don’t really see how Eliade’s authoritative voice makes him a modern until we compare him to someone who engages in the same kind of enquiry but from a distinctively not-modern approach. In his essay “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight”, Clifford Geertz is writing at roughly the same time as Eliade (the essay is an account of field work he had conducted in 1958). But there is a startling difference. Geertz places himself inside his own account. He introduces his essay by telling how he and his wife arrived in a village and could make no headway in the observations until one day, while watching the locals engage in traditional (and very illegal) gambling, the police raided the village and a local family hid the Geertz’s and even lied to the police on their behalf. Instantly, Geertz and his wife became co-conspirators and gained unprecedented access to life in the community. Implicit in the account is the anthropologist’s conundrum: it’s impossible to have both access and objectivity. Geertz doesn’t even pretend to be objective. Nor does he offer authoritative explanations. He sees what he sees and leaves it to the reader to determine whether his observations have any value.

Noting that difference, let’s return to Myth and Reality where Eliade makes a digression to talk about modern art. The idea here is that expressions of art in “civilized” (always in quotation marks) cultures are similar in form to the myth narratives of “primitive” cultures. In his chapter titled “Eschatology and Cosmogony”, he has been talking about the ways that religions, from cargo cults to Judeo-Christian believers, envision the end of the world, not as a final event, but as a clearing out of a degraded reality to make way for something new, or even to make way for a return to a paradisiacal state that may once have existed but has disappeared. Eliade sees modern art (e.g. Abstract Expressionism) as part of the same pattern. In a section called The “End of the World” in Modern Art, he writes:

Since the beginning of the century the plastic arts, as well as literature and music, have undergone such radical transformations that it has been possible to speak of a “destruction of the language of art.” Beginning in painting, this destruction of language has spread to poetry, to the novel, and just recently, with Ionesco, to the theater. In some cases there is a real annihilation of the established artistic Universe. Looking at some recent canvases, we get the impression that the artist wished to make tabula rasa of the entire history of painting. There is more than a destruction, there is a reversion to Chaos, to a sort of primordial massa confusa. Yet at the same time, contemplating such works, we sense that the artist is searching for something that he has not yet expressed. He had to make a clean sweep of the ruins and trash accumulated by the preceding plastic revolutions; he had to reach a germinal mode of matter, so that he could begin the history of art over again from zero. Among many modern artists we sense that the “destruction of the plastic language” is only the first phase of a more complex process and that the re-creation of a new Universe must necessarily follow.

In modern art the nihilism and pessimism of the first revolutionaries and demolishers represent attitudes that are already outmoded. Today no great artist believes in the degeneration and imminent disappearance of his art. From this point of view the modern artists’ attitude is like that of the “primitives”; they have contributed to the destruction of the World—that is, to the destruction of their World, their artistic Universe—in order to create another. But this cultural phenomenon is of the utmost importance, for it is primarily the artists who represent the genuine creative forces of a civilization or a society. Through their creation the artists anticipate what is to come—sometimes one or two generations later—in other sectors of social and cultural life.

In an earlier book, Myths, Dreams, and Mysteries, Eliade had applied this idea to poetry:

All poetry is an effort to re-create the language; in other words, to abolish current language, that of every day, and to invent a new, private and personal speech, in the last analysis secret. But poetic creation, like linguistic creation, implies the abolition of time—of the history concentrated in language—and tends towards the recovery of the paradisiac, primordial situation; of the days when one could create spontaneously, when the past did not exist because there was no consciousness of time, no memory of temporal duration. It is said, moreover, in our own day, that for a great poet the past does not exist: the poet discovers the world as though he were present at the cosmogonic moment, contemporaneous with the first day of the Creation. From a certain point of view, we may say that every great poet is re-making the world, for he is trying to see it as if there were no Time, no History. In this his attitude is strangely like that of the “primitive”, of the man in traditional society.

I wonder what Clifford Geertz would have said about poetry. Probably nothing so grand. No poet-as-shaman. No poet-as-prophet. I expect he’d be more likely to write about his personal encounters with poets as they go about the business of living their lives. Maybe he’d go to poetry reading and report on the experience. Maybe it would go something like this:

On a Saturday evening, I attended a poetry slam (as they are called here). I had hoped to blend in with the regular crowd, but locals immediately spotted me as a stranger in their midst. It was my mode of dress. I was so ordinary, I stood out. I should have dressed in an “original” or “unique” style. My accouterment should have expressed a certain “hipster” panache. However, as we shall see, in the end, they were quite accepting of me in spite of myself. The slam was held at a local bar which had a stage set up as if for a jazz trio. However, instead of musicians, it was poets who took turns stepping to the microphone. The event did not involve readings, per se. I had expected it would, but was quickly disabused of that expectation. Instead, participants engaged in improvisational declamations. They may have come prepared with a few thematic suggestions, but the greater part of their “reading” was an extemporaneous performance. In this respect, the comparison to a jazz trio was not inapt.

Things were going well and I was taking detailed notes, but had rather a lot to drink and that got me into trouble. Before I knew what had happened, I was onstage with several others and we were taking turns “performing” our rants. Some of it reminded me of “scat” in early American jazz clubs. However, I can’t be sure. What happened after that is a bit of a blur. I do know that when the bartender yelled last call, we spilled out onto the sidewalk and continued our slam, shouting poetry into the night. A police officer arrested us for drunk and disorderly conduct and we spent the next eight hours in a holding cell until we came before a justice of the peace where we received a stern lecture and a fine. It was a rather sour ending to what was otherwise a fine bit of field work.