No, this post is not about the T.S. Eliot play, but about an episode I’m writing as my excuse to participate in NaNoWriMo – the discovery of a body in a church and subsequent revelation that the priest had been having sex with the victim (when she was still alive). My aim is to take this news story and embed a fictional adaptation of it into a larger novel I’m working on. The curious thing is that when I revisit the news reports, I discover that my brain’s faulty memory has already done the adapting for me. For example, I could have sworn that the victim was a prostitute. I could have sworn that the priest had reached out to her as part of some kind of pastoral program. I could have sworn that the murderer, the custodian, had been motivated either by a desire to protect the priest from the corrupting influence of a prostitute, or by jealousy springing from some homoerotic rage, or both. It turns out there is no way to come up with any of this from the facts. It turns out it all comes from my own sick brain.

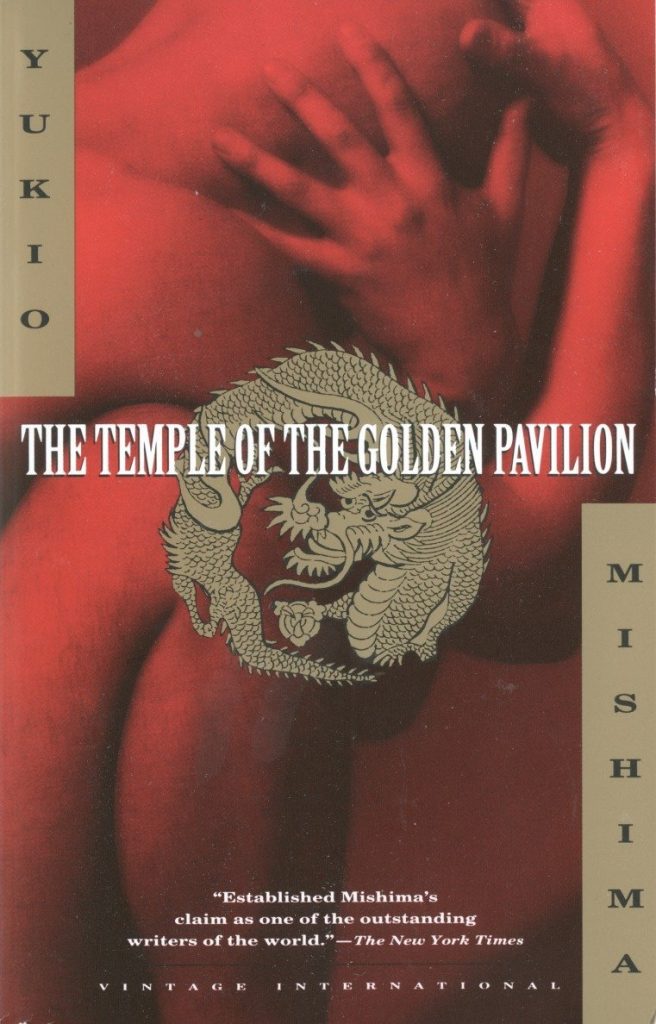

That’s not entirely true. Stories seem to fall into patterns all their own. Like sentences, they have a native syntax that determines outcomes quite apart from facts and logic. In a sense, all stories write themselves. I think that’s why we can detect patterns in our own writing that belong to things that have gone before. In my “murder in the cathedral” I see a storied heritage. I don’t trace my plot back to T.S. Eliot’s fictionalized account of the very real assassination of Thomas Becket. Instead, I trace it to Yukio Mishima’s Temple of the Golden Pavilion which itself was inspired by the very real 1950 arson of a Kyoto reliquary called Kinkaku-ji. Mishima told the story from the point of view of the arsonist, Mizoguchi, a Buddhist acolyte, and he provides a careful exposition of the young man’s deteriorating mental health.

I find surprising similarities between Mishima’s story and the adaptation I have made of my particular facts. The similarities suggest to me that I have been unconsciously influenced by Mishima. First, there is the priest, Dosen, whom Mizoguchi has seen with a geisha. Second, there is the friendship with Kashiwagi. This friendship follows a type that appears throughout literature (and life for that matter) – the co-dependent relationship between a dominant personality and a passive subordinate narrator. This may appear so often in literature because writers tend to assume the role of passive observer to other people’s actions. Mishima himself uses this type elsewhere. For example, in The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea, the son, Noboru, plays subordinate to The Chief who leads a gang of boys and goads them to acts of violence. Implicit in the type, and perhaps more obvious in Mishima’s works, is a homoerotic connection between the dominant and the subordinate. The completion of violence produces a sexual release.

In my account, the custodian kills the prostitute, not because it produces a sexual release in relation to the woman he is killing, but because he perceives her as an obstacle in his relationship with the priest. The act of killing her removes the obstacle and any sexual release is then transferred to the priest.

Time for me to stop yakking about it and get back to writing.