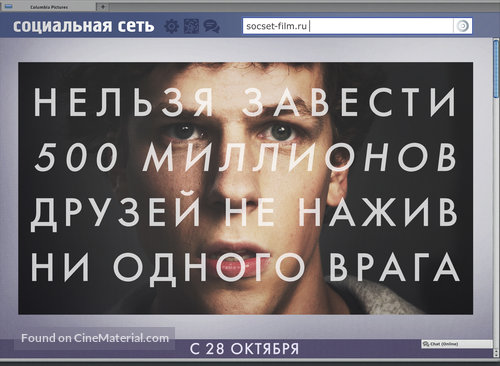

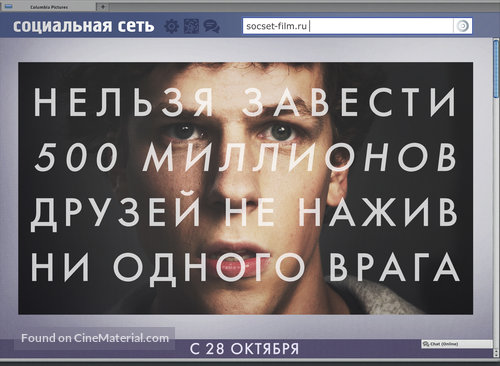

I saw The Social Network on opening night but didn’t post anything here because after the movie was over I went home and promptly forgot about it. My interest in the movie has been revived, not because of some scene that has lodged itself in my brain and won’t leave me alone, but because of mounting interest in the question: what does Mark Zuckerberg think of it? See Mashable, for example.

We live in an age plagued by literalism. And so it is easy to understand why most viewers would think The Social Network is a movie about a Harvard student named Mark Zuckerberg who allegedly stole source code from other Harvard students, developed a website called Facebook which now boasts more than half a billion members, became the world’s youngest billionaire, and ended up defending himself in a lawsuit launched by his Harvard class mates. If that were the case, this would be a documentary or a feature on 60 Minutes or more likely a segment on the Colbert Report. But The Social Network is none of these. It’s entertainment. It’s fluff. More to the point: it’s American fluff.

The film has a lot in common with heist movies (think Oceans 11) and B-grade war flicks (Behind Enemy Lines) which celebrate American ingenuity and impossible odds. Expressed in these terms, it’s plausible to rethink this much lauded film as a piece of navel lint. Think of it first as a heist film. All the elements are there: 1) a complicated scheme that involves the misappropriation of something valuable like gold bricks from a vault or code from a laptop, 2) an ordeal like prison or a lawsuit, and 3) a final acknowledgment that, notwithstanding the ordeal, the protagonist will get to keep his spoils. If we were to compare the extent of the spoils by setting Oceans 11 next to TSN, it would immediately strike us that TSN is one of the most far-fetched scams ever portrayed in film.

Now let’s consider it as an “against all odds” film: an awkward undergrad suffering from Social Anxiety Disorder or Asperger’s Syndrome overcomes improbable odds to become rich and famous, getting blow jobs in bathroom stalls and a million fans on Facebook. If he weren’t doing this, he’d be a soldier in Afghanistan surviving suicidal missions in the hills so that Ivy League undergraduates could enjoy all the freedoms of being an American — like getting blow jobs in bathroom stalls and a million fans on Facebook.

As entertainment, are these themes I care about? Are these themes I ought to care about? What possible interest could I have, what possible empathy could I feel, for yet another American CEO whose compensation is thousands of times more than his employees? Or am I supposed to watch this as an affirmation of that quintessentially American myth that if I try hard enough, apply just the right combination of elbow grease and inspiration, then I too will be able to nab stocks worth billions and get women to do me at the snap of a finger?

What is so entertaining about a film that reminds us that we live in a political economy structured to guarantee that a handful of people become obscenely wealthy at the expense of everybody else? If we take this film literally, as an account of things that have happened in the real world, then maybe we should be pissed off. If we take it as entertainment, as a vehicle for reaffirming a persistent social myth, then what we’re watching is a species of propaganda. Again, maybe we should be pissed off. Either way, maybe we should be pissed off.

We have all the ingredients here for a decent film. There’s a solid performance from Jesse Eisenberg, an enjoyable soundtrack, and good sense of storytelling in Aaron Sorkin’s screenplay and David Fincher’s direction. But the movie is mired by the facts. By supposing that it ought to adhere closely to facts in the real world, facts which are offensive in a fundamental way, Fincher creates an offensive movie. I don’t have to like the characters to like a film, but there has to be something in it for me to care about. It has to engage me. Instead, I end up gazing vacantly at the screen, much as Eisenberg gazes in his portrayal of an emotionally absent Zuckerberg.