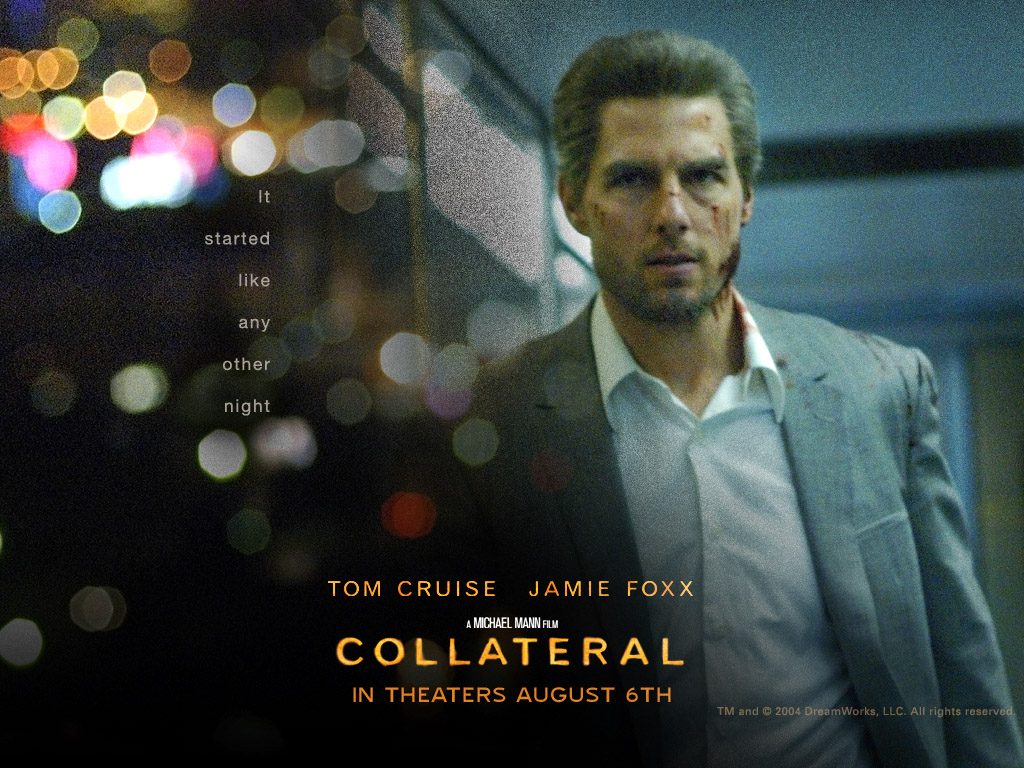

Last night, my son and I went to see Collateral, the new Michael Mann action flick starring Tom Cruise and Jamie Foxx. It was a slick show, and both leads gave a little extra so that their characters weren’t mere ciphers in a pro forma script.

I was amused by the clip that came before the feature presentation. A middle-aged black guy is talking. He looks a bit like George Foreman. He tells about the pride he takes in doing his job as a stuntman. He hopes he can give a little something by helping to entertain people who watch the movies. But, he says, a lot of people watch the movies without paying. That’s just stealing. It puts average guys like him out of work. Soft focus on a nice working-class schmo, then fade to black.

I don’t want you to be under any illusions. The only software I’ve ever paid for is the software that came pre-installed on my HD. Half the music I listen to I grabbed with an FTP client. And if a movie gets a bad review, but I want to be informed when I chit chat with other people, then I grab a copy however I can. I suppose that gives you license to dismiss what follows as a sad attempt to justify my indiscretions.

Or maybe nothing. After all, I don’t want you to be under any illusions. There is no nice working-class guy worried about losing his job as a stuntman. This is a character, just like any other character at the movies. This character is pitching a product—the Motion Picture Association of America. The MPAA wants you to believe that if all you rich movie-goers suddenly got your entertainment fix somewhere else, then poor studios like Universal and Warner Bros. wouldn’t be able to pay their poor working stiff actors (like Tom Cruise) their meager $20 million plus fees. Oh me, oh my.

Let us evil people stop and consider what it is that we are talking about. First, it is easier for me to state plainly what it is that I’m talking about because I am Canadian (no, I’m not talking about beer). As a Canadian, I fall outside the jurisdiction of American intellectual property law (notwithstanding George W’s desire to impose American law on everything that moves). The issue needs Canadians because, when American’s speak out, they end up being branded as subversive, etc., etc., and then freedom of speech issues cloud the waters. Second, although the MPAA and RIAA both like to spout off and run on about rights and laws and fairness, that’s all a load of crap. Nobody is interested in rights and laws and fairness. If we proceed down the path of rights and laws and fairness, then we soon discover that the very concepts that the MPAA and RIAA invoke are the concepts that will skewer them, or—to borrow that oft used phrase uttered by Adam West in “Batman”—they would be hoisted on their own petard (whatever a petard is). More on this later. There is only one thing which interests the MPAA and the RIAA—money. There is only one thing at issue—the bottom line. And so the only arguments they ought to be making, if they wish to be coherent, are economic arguments.

Apart from complaining about lost profits, why do organizations like the MPAA and RIAA never resort to economic arguments? Well … because they don’t work. Take our humble Compact Disc. The plastic itself costs about a cent or two. In 1990, we were paying approximately $20 per one cent piece of plastic. Why would anyone pay $20 for a piece of plastic? The RIAA told us it was value added plastic. We believed this at first, but as the years passed, we realized that the added value wasn’t so valuable after all. We didn’t want to pay $20 for a piece of plastic, one hit song and eleven more tracks of filler. It was a little bit like buying a dozen eggs, taking them home, then finding that all but one were stinking rotten. The only recourse was to exert our collective will and demand better. The most lucrative market for CD’s (the 18 to 34 male demographic) was the group of people best equipped to find a market solution to their problem i.e. they were computer literate. Some developed psycho-acoustical algorithms to compress digital tracks by a ratio of 10:1 (MP3’s) while others, like Shawn Fanning, wrote cool appz like Napster in order to share those MP3’s.

What was the result of this protest? One result was that media moguls everywhere hired spin consultants to help dress them in white suits and blazing armour, while persuading people that the angry young consumers were subversive. They called them “pirates.” Arggh. Another result was that BMG, the German media giant, bought out Fanning and has just reinvented Napster as an agent of legitimacy. Poor Fanning. So young. And now so rich. I admire him. He presented the music establishment with a threat, and they gave him lots and lots of money. To the working stiff in the street, that would be extortion (a criminal offence). But I guess the definition changes as the stakes go up. But the most telling result is that the price of CD’s dropped significantly across the board, and more titles appeared in remainder bins and on discount racks. Such a move would not occur on a sustained basis if it would result in a loss. In other words, the recording industry was forced to narrow its margins. At the same time, it (and others) have started selling MP3’s online so that consumers no longer have to purchase an entire album if they are concerned that most of the tracks will be crap. That, in turn motivates recording artists to produce a higher quality product. All these changes lead to the conclusion that CD prices have been artificially inflated for years. Could this point to anti-competitive behaviour? I smell a forensic audit in the air. I wonder how many more CD’s and DVD’s that working grunt stuntman could have bought if the company he had worked for hadn’t been screwing him over for so many years.

A different spin may help. Prior to the collapse of Russia, official economic policy was dictated by marxist ideology. Private property didn’t exist. Therefore, proprietary interests in personal property were impossible. Nevertheless, a black market thrived. It thrived in proportion as the state failed to provide the necessaries of life.

Now let’s walk down the path of rights and laws and fairness. Here’s a whirlwind tour of anglo-american copyright law. In medieval times, there was no such thing. Your ideas, your artistry, your creations—these fell under the control of either the church or the guilds with a few extraordinary talents receiving the direct patronage of nobility. It wasn’t until 1710, with the Statute of Anne, that any government anywhere in the world attached proprietary rights to intellectual products for the benefit of their creators. This statute was the first attempt to give more power to individual creators so that they could obtain more equitable compensation for their work.

Here are some fundamental principals of copyright law that have remained intact in all the jurisdictions that have adopted the copyright principle:

1) Copyright does not protect ideas. It is the writing, image, etc. itself which is protected; not its content.

2) Copyright exists. Period. You don’t have to do anything special to denote that your work is subject to copyright protection. You don’t need a “©” to assert your right.

3) Copyright is of finite duration. Duration has varied from time to time and from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. In Canada, copyright expires upon death, or upon 50 years following the year in which the author died. In the U.S., the Sonny Bono Copyright Extension Act now extends that term to 95 years.

4) Copyright is freely transferable. You can sell it, give it away, bequeath it, even lease it.

In addition, there are two practical considerations:\

5) You can enforce your rights only in those jurisdictions which a) recognize your rights, and b) recognize you. For example, if Mark Twain had accused Stephen Leacock of passing off Huckleberry Finn as his own work, he might not have been able to do so for two reasons. First, he was American and so had no standing in a Canadian court. Second, he was trying to assert his right under American law and no Canadian court could possibly be seized of American law.

The solution to this dilemma came in 1971 with the Berne Convention to which both Canada and the United States are signatories.

6) Where the country is a federation (e.g. Australia, Canada, the United States), it is the federal government which has jurisdiction over copyright. In other words, if you live in Florida, you don’t go to Jacksonville to seek redress; you go to Washington, D.C.

A principle which grew up alongside copyright was the idea of moral rights. This is the right to the integrity of the work. Integrity means that it is not used in ways that subvert it or undermine it. For example, it would compromise an artist’s moral rights to use well-known music as an accompaniment to lyrics that celebrate sex with children. Moral rights and copyright exist concurrently in the same work. However, the holders of those rights don’t have to be the same person. This often occurs because a copyright holder cannot divest himself of moral rights. Thus, someone who sells the rights in a song to a recording company can nevertheless prevent the company from using the song in a manner that contravenes the author’s moral rights.

Let’s take one more trip down the copyright lane—the Digital Millennium Copyright Act which was enacted in 1998. Thankfully, this is an American statute and I’m not American. It is the result of the powerful lobby by such groups as the MPAA and the RIAA, as well as pressure from WIPO, and it specifically targets so-called pirates of digital media such as CD’s, DVD’s and software.

Grey Areas

There will always be grey areas. These are the areas right along the line which demarks rights from wrongs. These are the areas that will always be subject to debate. For example:

• What is scratch music? You put a piece of vinyl on a turntable and then you move it back and forth underneath the stylus. Most of it is scratchy, but now and again, you can hear bits of music from the vinyl. Are the milliseconds of sound subject to copyright protection? The same question can be asked of hip hop, rap, collages, papier maché, etc.

• There are exceptions carved out of copyrights for things like fair use and educational citation. For example, you can reproduce small portions of a work in the context of a book review or a university essay. But how small is “small?” Is it a chapter? A paragraph? A sentence? And what is educational? How about showing a Veggie Tales video to five-year-olds at church? If you call it Sunday School, will people notice that it’s just glorified baby sitting?

• What is parody? People find parody entertaining. We can watch it every night during the opening monologues of the late night talk show hosts. It’s easy enough to poke gentle fun at politicians and celebrities. We call this freedom of expression. But it’s quite another thing when the object of our parody is a film or a play or a book. By its very nature, parody reproduces portions of the object of its fun. Maybe it falls afoul of moral rights too.

• There is a strong counter-argument afoot that the hyper—vigilance of major players in the entertainment industry will ultimately stifle, rather than encourage, creativity. Rights protection hasn’t protected anything; it seeks to commodify something that cannot be commodified—culture. Like the people of Russia, culture will emerge elsewhere, beyond the bounds of authority.

The Big Picture

Copyright got its footing in the legal terrain by creating protections for the benefit of individuals who were powerless against larger entities like church, guilds, and the state. Now, the larger entities seek to appropriate copyright for their own benefit. These same entities already control whose work gets distributed and who gets compensated. The “artists” in their stables are in no immediate fear of going hungry. But we rarely hear about those thousands whom the large entities reject. In short, groups like the MPAA and the RIAA seek to turn copyright on its head. They seek to subvert it. Isn’t that a violation of some moral right?

Disclaimer

This is the stuff I have to say because I am a lawyer and I don’t want to expose myself to liability.

1) None of the foregoing should be relied upon as a substitute for legal advice. (If you do, then you are an idiot and deserve whatever consequences befall you.)

2) The opinions expressed herein are solely the opinions of the author and cannot be relied upon. (i.e. even as I write this I am drinking 15 year old Balvenie single malt whisky.)

3) If you have specific legal concerns, then you should consult a lawyer in person who can then provide you with advice specific to your specific concerns which you can rely upon.