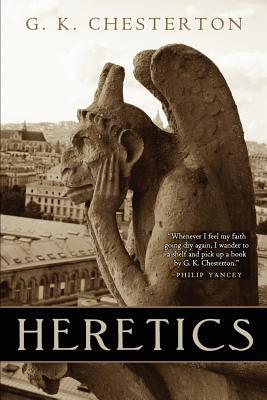

Cage Match: measuring the punditry of Ann Coulter against G. K. Chesterton’s Heretics.

In my previous post I touched on a question of propriety in writing: is it acceptable for an author of fiction to allow her work to be influenced by politics? In this post I want to turn the question on its head and ask: is it acceptable for an author of politics to allow her work to be influenced by fiction? I had been fretting that perhaps there was something unsettling about Laila Lalami’s novel because she seems to conclude with what could be construed as a declaration of intention. A novel should remain neatly contained between two covers and sit silent upon the shelf except at certain appointed times. To suggest that a novel should impact upon the real concerns of real people smacks of heresy. Entertain us but don’t force us to think deeply about our lives. In the same way, it is heretical to demand that a pundit execute opinions with art or grace, for then readers might mistake her motives and suppose that the pundit has designs upon our aesthetic sensibilities. To care about how a thought is expressed would be unconscionable.

Within the hagiography of political writing, the most orthodox of saints is doubtless Ann Coulter—orthodox not by any measure of her thinking (which is neither here nor there) but by her scrupulous refusal to pander to those who care about how the English language is crafted. The puzzle here is one of causality. Is there a relationship between the crudeness of the expression and the crudeness of the thinking? For example, perhaps the absence of subtlety in her expression betrays a deep–seated spiritual poverty that renders nuanced argument impossible. Or, conversely, perhaps the life–long habit of thinking about issues in the simplest of terms has rendered her incapable of meaningful affect in her writing. Whatever the analysis, I find that when I read her I almost believe I am having a conversation with a piece of cardboard.

But why?

Finding an answer to this question is the challenge at hand.

I must confess in advance that I have no definitive answer to this question—only an assortment of suggestions and observations. At the same time, I shall draw a comparison to another political pundit. I do this in order to avoid the accusation that I’m just another one of Coulter’s mythical “liberals” who is merely using a critique of her style to launch a back–door attack on her politics. I would never do such a thing because a) I am afraid of what an encounter with Ms. Coulter’s back door might look like, & b) it would be dishonourable to attack something so pitiable as an incoherent politic. Instead, I introduce another pundit, someone with whom I frequently disagree, someone whose opinionated political views often attract my anger, yet someone who nevertheless inspires my admiration by the fullness of his thinking and more particularly by the command of his language. I refer to G.K. Chesterton, who has the added advantage of being dead. I expect that Ms. Coulter would seriously consider such a state of affairs if she believed it was a prudent career move. Next to the brilliance of Chesterton we discover what a pallid presence Ann Coulter makes for herself in contemporary political debate.

So let’s consider the wit which is Ann Coulter. I will not include links to her web site as I have no desire to assist her search engine rankings, but I will quote at length. Consider, for example, her deep theological commitments as revealed in reference to the late Rev. Jerry Falwell:

Falwell was a perfected Christian. He exuded Christian love for all men, hating sin while loving sinners. This is as opposed to liberals, who just love sinners. Like Christ ministering to prostitutes, Falwell regularly left the safe confines of his church to show up in such benighted venues as CNN.

What follows from this is a rambling harangue of homosexuality which concludes with remarks about Tinky Winky of Teletubby fame. Or writing in reference to one of civilization’s great evils, immigration:

What evidence is there for the proposition that American culture will leap like a tenacious form of tuberculosis to today’s immigrants? Americans display no evident desire to defend their culture, much less transmit it, and immigrants show no evident desire to adopt it.

To the contrary, immigrants are replacing American culture with Latin American culture. Their apparent constant need to demonstrate is just one example.

See how the language (so lovingly crafted) just leaps off the tongue, like, like what?—like a tenacious form of tuberculosis. Or more recently we witness her penchant for warm race relations:

In 1960, whites were 90 percent of the country. The Census Bureau recently estimated that whites already account for less than two-thirds of the population and will be a minority by 2050. Other estimates put that day much sooner.

One may assume the new majority will not be such compassionate overlords as the white majority has been. If this sort of drastic change were legally imposed on any group other than white Americans, it would be called genocide.

Admitting non–whites into a country is genocide? So are we to understand that white Americans may soon face the same horrors as Bosnian Muslims? Or the Tutsi of Rwanda? Or Jews of the Holocaust? Writing tip for Coulter: a dictionary is a helpful tool when having difficulty grasping the meaning of a word.

There is a pristine integrity about a woman who endorses the value of laissez faire capitalism, and lives it thoroughly by making her primary objective the sale of her book. Her life has all the logic of prostitution—or at least the account of prostitution which Coulter–the–social–worker provides. In Coulter’s universe, prostitution is a choice one makes in a free market. And since prostitution involves the biblical sin of fornication, it is fundamentally a moral choice. Her explanation of prostitution does not allow for such factors as an absence of social supports, structural sin, economic desperation, enslavement, or male domination. Quite simply: prostitutes are rational economic actors who have allowed their bodies to be allocated to the highest valued use. Here, Coulter treads upon the same ground as Law–and–Economics guru Richard Posner (now a judge for the Seventh Circuit U.S. court of appeals) who once suggested that the purpose of marriage is to reduce the transaction costs of sexual intercourse.

By the same reasoning, it is entirely acceptable to write absolutely anything no matter how outrageous or nonsensical so long as it helps to sell books. And so, without concern, she can write: “With Nicolas Sarkozy’s decisive victory as the new president of France, the French have produced their first pro–American ruler since Louis XVI. In celebration of France’s spectacular return to Western civilization…” It makes no difference that she is ludicrous; her only goal is to snatch away enough of Jerry Springer’s audience to make her agent happy. Yes. A woman of utmost integrity for her strict adherence to the rules of the marketplace—which, by her definition, makes her a prostitute.

But if money is not her object, then maybe what she seeks is attention. Perhaps it makes more sense to characterize her as standing in the vaudeville tradition—an entertainer—a passing amusement that is forgotten as soon as the tent pegs are pulled. No doubt she is the darling of the current affairs circuit. So long as the participants in a given TV segment have been sufficiently polarized by artificial parameters, then the resulting conflict boosts ratings while allowing the networks to claim that they are promoting a healthy democracy by encouraging “meaningful debate” or “dialogue” or “discourse” or whatever other euphemism they can invent for an utterly contrived soft shoe routine.

But here we discover a wonderful foil in G. K. Chesterton. Superficially, his approach has much in common with Ms. Coulter. He likes to open with an outrageous or contrarian claim that sets the reader on edge. So, for example, writing in 1905 in his book, Heretics:

There is a great deal of protest made from one quarter or another nowadays against the influence of that new journalism which is associated with the names of Sir Alfred Harmsworth and Mr. Pearson. But almost everybody who attacks it attacks on the ground that it is very sensational, very violent and vulgar and startling. I am speaking in no affected contrariety, but in the simplicity of a genuine personal impression, when I say that this journalism offends as being not sensational or violent enough.

Or again (and quite pointedly in this context):

In one sense, at any rate, it is more valuable to read bad literature than good literature. Good literature may tell us the mind of one man; but bad literature may tell us the mind of many men. A good novel tells us the truth about its hero; but a bad novel tells us the truth about its author. It does much more than that, it tells us the truth about its readers; and, oddly enough, it tells us this all the more the more cynical and immoral be the motive of its manufacture. … Thus a man, like many men of real culture in our day, might learn from good literature nothing except the power to appreciate good literature. But from bad literature he might learn to govern empires and look over the map of mankind.

But notwithstanding his love of the contrary, and notwithstanding his love of the bold pronouncement, there are significant distinctions. The first may be found in Chesterton’s politics. Coulter observes the world through a highly polarized lens and writes hardly a paragraph without lauding herself as champion of the true conservative who must do battle against the evils of liberalism. Her call for a return to the ideal era of the 1950’s is no doubt motivated in part by her admiration for Senator Joseph McCarthy who was likewise paranoid about the politics of compassion. However, Chesterton’s view of the world cannot be neatly categorized in this way. On some matters he gives the impression of a firmly held conservatism. So, for example, he takes frequent pot–shots at his friend and notorious socialist, George Bernard Shaw. At the same time, his views on the British Empire are ambivalent at best as we see in his attitude towards Rudyard Kipling. He exhibits no particular regard for the Boer War and states quite plainly that a long–standing tradition as an imperial power gives Britain no particular cause to believe it has a continuing entitlement to its status.

The same ambivalence affects his religious views. He demonstrates a rather un–English affinity for Roman Catholicism (he ultimately left the Church of England in favour of Rome) and expresses disdain for the “undenominational religions” but at the same time is virulently opposed to dogma in any form. His aesthetics is similarly nuanced. He expresses great admiration for the work of Ibsen, but wonders aloud if the absence of a moral grounding undermines its legitimacy. But he has no hesitation to ask the converse question as well: are expressions of a heartfelt morality worth reading if they aren’t also grounded in a worthy aesthetics? Chesterton answers this question by his own example. What sets him apart from Coulter is, above all, an artful style that bears reading and rereading. Perhaps nothing more plainly attests to Chesterton’s quality than the fact that after more than a hundred years almost all of his nearly eighty volumes remain in print.

On the other hand, within a few short years I expect that Coulter’s single volume will leap (like a tenacious form of tuberculosis?) from remainder bin to paper shredder—a fate it amply deserves.