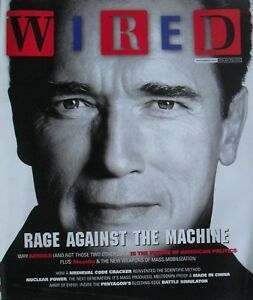

In this month’s issue of Wired, there is an article which gives me much encouragement. It’s an account of a psychologist named Gordon Rugg who, in his spare time, has devoted himself to the puzzle of the Voynich manuscript. This is a medieval manuscript which appears to have been encrypted by its author. No one has been able to crack the code. You can view a page from the manuscript which resides at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University.

In short, Rugg’s solution is to provide proofs that the manuscript is a hoax. But the real story has nothing to do with Rugg’s findings; it has everything to do with his method. Typically, people who have tried (and failed) to crack this puzzle, approached the problem from an area of specialization. While their expertise empowered them within the sphere of their particular specialization, nevertheless, outside that sphere, they had nothing new to offer and—more likely—their expertise was a hindrance.

Rugg’s advantage was that he had no area of specialization which he could bring to the problem. He was a generalist. He looked at each of the areas of expertise—cryptography, linguistics, medieval studies, etc.—and evaluated what each brought to the task, and what each lacked. The Voynich manuscript is merely an exercise. The fate of the world doesn’t hinge on determining whether or not it can be decoded. But there are many valuable applications for Rugg’s method.

Rugg celebrates the generalist. This comes as a delight to me. I am interested in everything (except maybe golf), but the pursuit of one thing or another requires a significant investment of time. There is that stereotype of the shopaholic woman running from one boutique to another. I do the same thing with books. I ran out of shelves long ago and now my books are piled two deep against my wall. When I look at all my books, I despair. When will I ever find time to read them all? So much to learn. So little time. I will never be a specialist. After a while, I see all the possibilities, and then I grow bored. Something else clamours for my attention. And so I move on. Tamiko is glad I don’t treat relationships the same way I treat knowledge!

I am reminded of an episode of MASH when the 4077th gets a new surgeon who turns out to be an impostor. (It’s Season 1, Episode 18, “Dear Dad … Again” for MASH fans.) When they discover the truth, Hawkeye confronts the man. He has remarkable skills. Why not make the effort to get a medical degree? The man explains that he hasn’t the patience to get a piece of paper. When he leaves, he blesses Hawkeye. Now, he’s a rabbi.

The problem is a surfeit of information—a state of affairs that has never existed until these past few years. For example, Rugg’s next puzzle is Alzheimer’s disease. The article states that the National Institute of Health’s PubMed database contains 40,000 articles on the disease. It would be impossible for an individual to assimilate all that information and develop conclusions from it. I have encountered the same problem elsewhere. I have found myself drawn to the writings of Ludwig Wittgenstein and wish to learn more about both him and his writings. I have read that, to date, more than 20,000 books have been published on the subject of Ludwig Wittgenstein. All that writing for a man who published only one slim volume and left another which was published posthumously. Even if I were able to read all those books, I would still have two formidable tasks:

• I would have to make sense of them. That is, I would have to understand them in relation to myself.

• I would have to place them somewhere. That is, I would have to understand them in relation to everything else that is known.

Another example of information surfeit is blogging. Each day, a million or more people, post tidbits to their personal web space. I want to know what other people think. I want to know about their lives and about their problems and the hurts. I am not a voyeur; I am an empathetic onlooker. But how can I be this, when I scarcely have time in a day to hack out a few words for myself?

The only way we can overcome this mountain of information is by choosing our words carefully. I have nothing more to write.