It seems fitting at today’s convocation that my theology degree should have been conferred on me by Norman Jewison, the director of such movies as Rollerball and Fiddler on the Roof. Technically my MTS (Master of Theological Studies) wasn’t conferred by Norman Jewison; it was conferred by Victoria University in the University of Toronto, and Emmanuel College is one of its Colleges. Sounds complicated no? Vic has a song that’s probably 150 years old that helps to sort through the complicatedness. There’s a tendency to forget about Emmanuel College, but the song reminds us that Emmanuel has a place at Vic too.

My father sent me to Victoria

And resolved that I should be a man

And so I settled down

In a quiet college town

On the Old Ontario Strand.(chorus)

On the Old Ontario Strand, my boys

Where Victoria ever more will stand,

For has she not stood since the time of the flood

On the Old Ontario Strand.At first they used me rather roughly

As I the fearful gauntlet ran,

They tossed me all about,

And they turned me inside out

On the Old Ontario Strand.\And don’t forget the theologians,

For they’re the finest in the land,

And with a little leaven

They will send us all to heaven

On the Old Ontario Strand.

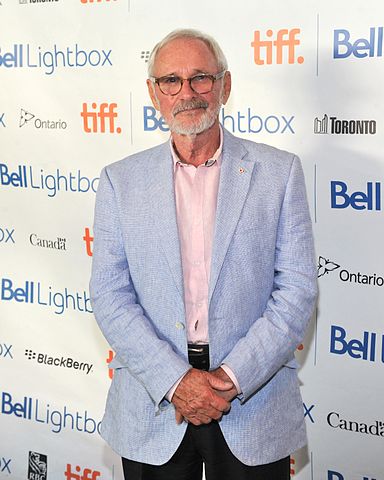

So why would I say it’s fitting that Norman Jewison should be present to help confer this degree? Well for one thing I first graduated from Vic in 1985 with a degree in English and in that year Vic conferred on Norman Jewison an honorary doctorate. He spoke at our convocation then. So it feels to me like the wheel is turning around. Chancellor Jewison’s presence reminds me of where I came from and also, with a note of sadness, it reminds me of what I’ve left behind.

I first opted for studies in English lit because I love to read and have a fascination for words. I still can’t figure out what words are or how they work or why they’re important or why they have such a hold on me. But subsequent studies have been an extension of that first fascination. So, for me, the study of law was an exploration of how words can be deployed to ground human conduct. And theology has been an exploration of how the word can be deployed to ground our apprehension of ultimacy.

However, as I proceed on this journey, I find myself growing word-weary. I think of all the papers I’ve written for school—probably running to a thousand pages all told—and how little of it will ever be read by anybody. I look at the stats for this blog and see that it contains 1,548,955 characters to date. That’s 309,791 words or the equivalent of 1,239 pages. That’s an awful lot of yakking, and most of the ideas aren’t terribly original either.

I think my word-weariness comes from a distrust of what theological types call apologetics—which is not the impulse to say “I’m sorry” (though a lot of theological types should consider saying “I’m sorry” on a regular basis). “Apologetics” has its roots in the classical Greek language and in the religious context refers to the art of explaining and justifying theological propositions. It’s a wordy enterprise. But it makes some dubious assumptions:\r\n

> the things theologians try to explain are explainable

> words are the best way to understand things

> understanding happens only in our intellect

> theologians are the best qualified people to explain things

> the average person cares about the claims theologians try to explain and justify

While none of these assumptions is necessarily false, there are other things afoot that undermine the apologetic process. Chief among these is what I would call the colonizing impulse. While the colonizing impulse most clearly reveals itself in the grand sweep of history through the collision of civilizations, it is equally evident in the relations between individuals. The colonizing impulse arises whenever a person tries to persuade, entice, cajole, coax or even force another to his point of view. It produces a relationship of inequality where one idea, view of the world, or way of life is subordinated to another. There is a sense of arrogance behind the colonizing impulse. But more significantly there is the smell of fear in it.

Between individuals it is the fear of loneliness that motivates us to draw others into our view of the world. We fear that the ancient myths of Eden and of Babel may be true—that we live forever alienated both from our world and from each other. We strive through sex, through art, through worship, even through violence, to reclaim an integrated sense of being, to return to the garden, to achieve a Pentecost. And so we yak and yak and yak and hope that others might affirm the nonsense that issues from our lips and from our pens.

When I am honest with myself, I can’t help but note the irony that even with these words I am sorely tempted to hope for your affirmation, that maybe one or two of you will post a comment which will boost my self-esteem by assuring me that my point of view has some validity. And yet there is a sense in which spiritual journeying must always resist the colonizing impulse and proceed alone. Giving expression to thoughts, as I do in this blog, is largely pointless if persuasion is my aim. It best serves me as a tool to clarify my own thinking—like journaling. But I do it publicly. I wonder why? Maybe so that others can take heart in my stumbling.

So why the sense of return? Why do I feel a tug to the days of my English degree? Some of the works I studied back then were overtly didactic. I read allegories like Edmund Spenser and Herman Melville. Not surprisingly, both were products of great colonizing nations. But the greater part of my reading defied an easy exegesis. I think in particular of works by Nathanial West and Flannery O’Connor and Samuel Beckett. I remember how impatient I became with critics who destroyed the pleasure of reading a poem by explaining it. It’s the old case of “the letter killeth while the spirit giveth life.” If T.S. Eliot thought he could say it better as an essay, then he would have written “The Four Quartets” as a lecture series. But what he gave us was poetry. Why do critics presume that something already stated perfectly requires restating? Why do theologians presume that matters of the spirit are best understood by talking and talking ad nauseam?

So, now that Chancellor Jewison has uttered his magic incantations over me, I’ve made two resolutions:

1. Spend more of my theological energies with my mouth shut.

2. Write more material that makes no pretense of explaining anything.

Photo Credit: Canadian Film Centre from Toronto, Canada – subject to Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) License