When Canadians do the hokey-pokey, that’s what it”s all aboot. Can someone please tell me what it’s all aboot-er-about that there’s a proliferation of (American) TV shows that invent and then ridicule their invented version of the way Canadians speak? As a Canadian, I’ve never once said aboot. Nobody I know talks that way. I say ”eh” all the time, as do all my friends. I’m willing to own that one. And I”m always saying ”I’m sorry” (but that’s just passive-aggressive Canuck-speak for ”get the fuck out of my way, eh”). So where does the stereotype come from?

Aboot on U.S. TV

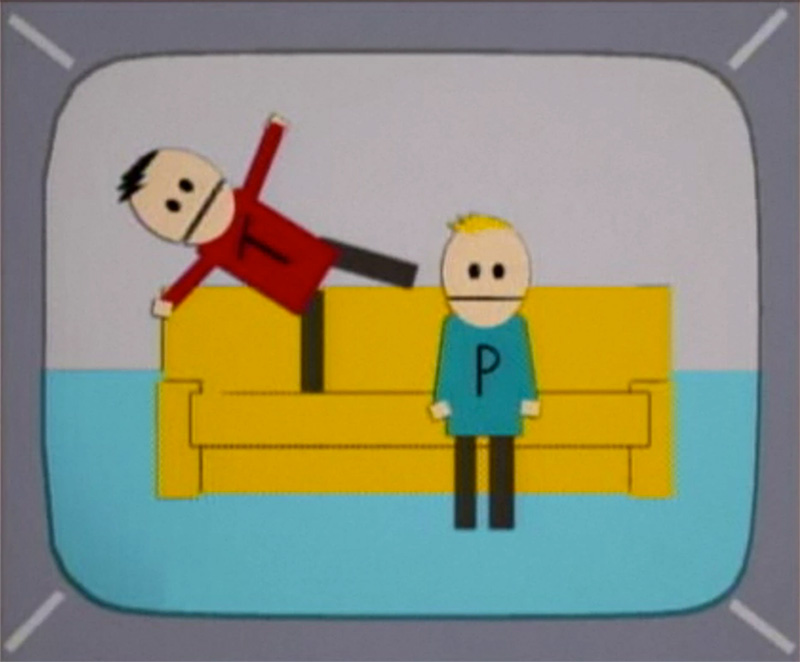

Sunday night, my wife and I spent a romantic evening watching the South Park movie. The movie opens with the kids sneaking off to watch the latest Terrance & Phillip movie, Asses of Fire. The parents are appalled that their children are watching such filthy foul-mouthed farting stuff. Since T & P come from Canada, the parents decide to blame Canada for everything that’s going wrong with their kids. Things escalate and the parents persuade the president to declare war on Canada. (Canada retaliates by dropping bombs on the Baldwin brothers.) Then comes the crucial scene: a speech by Canada’s ambassador to the UN when he uses the word ”aboot” and all the other delegates laugh at him.

That’s one possible source of the aboot stereotype. Another is the Canadian episode of How I Met Your Mother. The character, Robin, is Canadian, and in this particular episode, we learn aboot – I mean about – her sordid past. She used to be a pop star in Canada. The episode features cameos from people connected (mostly) to the Canadian music scene – Stephen Page, Geddy Lee, kd lang. There are lots of references to hockey, Tim Hortons and … the word aboot. Why?

Aboot in Canada

In Canada – or at least in the version of Canada I encounter when I go to real places like Moose Jaw and Kapuskasing – I’m hard-pressed to find real Canadian people who say aboot. In fact, the dialect so prized in U.S. broadcasting is as prevalent in Canada as the U.S. A paradigm of this dialect (we don’t think of it as a dialect because it’s the dominant mode of English-language speech in North American media) is the late Peter Jennings, anchor of ABC news, born in Toronto. I guarantee that Peter Jennings never once said aboot.

There is a more plausible explanation – This Hour Has Twenty-Two Minutes. Mary Walsh and Rick Mercer sometimes say aboot. But what do you expect? Both were born in St. John’s. Rick Mercer’s Talking To Americans has given Canadians a lot of laughs at the expense of our friends to the south. Maybe the aboot thing is a personal vendetta against Mr. Mercer.

Placelessness & West-Central Canadian English

In a way, I wish I said aboot when I speak. It’s boring at times to speak (and find that you can’t help but speak) in the dominant voice. Because of its dominance, my dialect gives my speech a quality of placelessness that is well suited to venues like airports, large chain hotels, convention centres, and shopping malls. Sometimes I wish I could tell people that I come from a remote fishing village with its own lilt and customs.

I feel acutely a tension between the forces of economic and cultural globalism on the one hand (with their demand for standardization and conformity) and the need to assert personal identity through the particular and the local on the other. A different way to express the tension is to speak of power and resistance. The fine-grained grittiness of unique experience gives me an antidote to the sensation that the world of systems and multinationals and media conglomerates is swallowing me whole. If I used the word aboot, and if it flowed from my tongue as freely as spit, then it would remind me daily that I don’t come from America, that I come from my own sweet place in the world.

Commercial Realism & Robotic Writing

The same is true of my writing which, as much as my speech, betrays the hardened plastic robot behind these words. I don’t want to write like a robot, but, as with my speech, I find it difficult to unlearn my early programming. James Wood offers a term to describe robotic writing, at least as it appears in fiction. He calls it commercial realism. I’m sure analogous terms must exist to describe robotic writing in other genres. Robotic non-fiction. Robotic news reportage. Robotic editorials. Robotic poetry.

Yesterday I did something I haven’t done in a long time. I ignored my Twitter account and opened my long-dormant RSS aggregator. (Basically, Twitter functions like an RSS aggregator, only more fluid – or more disorganized depending on your point of view.) I scrolled through my subscriptions – thousands of stories all forced to conform to the demands of my reading device (an iPad mini). Content aside, there seemed little difference between news reportage from Al Jazeera, say, and the literary/cultural soup of HTMLGIANT. Linguistcally, these posts are more or less the same. Admittedly, I’ve selected them that way. They conform to my often unexamined expectations and assumptions about what counts as proper expression for online posts. If they used words like aboot, I’d make fun of them just like the members of the UN General Assembly made fun of the Canadian ambassador in South Park. I’d call them hick blogs and ignore them.

In my Twitter feed (but not my RSS aggregator), I follow a fair smattering of writerly tweeters – lots of advice aboot-er-about how to grab this new writing medium by the balls and make a go of it. So, for example, if you want to write an eBook, the sum of all that writerly wisdom can be distilled to this: whatever advice we used to give aboot writing a commercially successful print-based book, that”s what you need to do when you publish your eBook. And so outlets like Apple, Amazon, Smashwords, etc. are bursting at the seams with e-versions of commercial realism. Robotic non-fiction. Robotic news reportage. Robotic editorials. Robotic poetry. You can buy it anywhere in the world and it reads like it was written anywhere and nowhere. The McDonald’s next door. The Antarctic. The moon.

But this is supposed to be a new and newly emerging medium. Why make it conform to the rules of the preceding medium. Why not reinvent it? Work it from the ground up? Or develop a new kind of content? Or a new voice? Or own it? Wholly own it? Why not take the words you deliver through this universally accessible format and make them so idiosyncratic, so unique, so thoroughly local, that they could only have come from you? Maybe that’s what it’s all aboot.