Most people, or at least most people who write, or at least most people who write novels, are familiar with at least one quote from Mao II. It goes like this:

He looked at the sentence, six disconsolate words, and saw the entire book as it took occasional shape in his mind, a neutered near-human dragging through the house, humpbacked, hydrocephalic, with puckered lips and soft skin, dribbling brain fluid from its mouth.

Later on:

I keep seeing my book wandering through the halls. There the thing is, creeping feebly, if you can imagine a naked humped creature with filed-down genitals, only worse, because its head bulges at the top and there’s a gargoylish tongue jutting at a corner of the mouth and truly terrible feet. It tries to cling to me, to touch and fasten. A cretin, a distort. Water-bloated, slobbering, incontinent.

Still later:

Bill thought he saw his book across the room, obese and lye-splashed, the face an acid spatter, zipped up and decolored, with broken teeth glinting out of the pulp.

Sometimes the quotes get attributed to DeLillo straight up, but as the last quote reveals, these are the rants of DeLillo’s main character, Bill Gray, who is struggling with his latest novel. Unlike DeLillo, who has fifteen novels to his credit and appears to have no difficulty getting them finished, Bill published two successful novels before entering into a protracted dry spell. He has become more famous for his seclusion than for his writing. He is Salingeresque in his hostility to the public eye.

I think other passages deserve more attention. For example, pages 40 and 41 gaze at one another with a canny prescience. On page 40, we have the image of the Twin Towers. On page 41, we have a discussion of terrorism and danger on planes. Mao II was published in 1991, a full decade before 9/11. And yet there it is.

The problem it seems is that “[t]here’s a curious knot that binds novelists and terrorists.” But novelists and terrorists are joined in an inverse relationship. “What terrorists gain, novelists lose.” Bill once believed that the novelist’s job is to startle people in a way that changes public consciousness, to wake people up to the ways that power wrecks their lives. But terrorism has usurped that role. Violence captures all the attention. The public is tone deaf and can’t pull the subtler lines from all the media noise that terror inspires. The public has become desensitized to reason and metaphor and symbolic expression. All that counts is the explosion. “In societies reduced to blur and glut, terror is the only meaningful act.” Bill’s third novel, although completed, remains on its shelf, irrelevant or ineffectual or maybe pointless in a world such as ours.

Bill is summoned to New York by his editor, an old friend named Charlie whom he hasn’t seen in years, not since the days when they believed the point of literature was “getting drunk and getting laid.” Charlie tells him a Swiss poet has been kidnapped by a terrorist group in Lebanon. He has been in discussions with a man named George who is connected to the group and they think they can secure the poet’s release. If someone of Bill’s stature were to make a public appearance, read a few of the hostage’s poems, endorse the cause of the terrorists …

Charlie’s motives are a bit dodgy. Sure, it would be great to rescue an obscure poet, but it would be greater if he could get his hands on Bill’s book. That would be a real coup. And it would make some money, too.

Bill flies to London and meets with George. A bomb detonates. Some glass flies.

The problem with terrorists is that, although they draw attention to their cause, they kill innocent people. Maybe that’s where the bond with novelists comes unraveled. As Bill reflects in his meeting with George:

When you inflict punishment on someone who is not guilty, when you fell rooms with innocent victims, you begin to empty the world of meaning and erect a separate mental state, the mind consuming what’s outside itself, replacing real things with plots and fictions. One fiction taking the world narrowly into itself, the other fiction pushing out toward the social order, trying to unfold into it. He could have told George a writer creates a character as a way to reveal consciousness, increase the flow of meaning. This is how we reply to power and beat back our fear. By extending the pitch of consciousness and human possibility.

In Mao II, power takes many forms. But regardless of form, its primary method is to drain the world of meaning. The novel opens with a mass marriage performed by the Reverend Sun Myung Moon in a baseball stadium and closes with millions of people grieving in the streets of Tehran on the death of the Ayatollah Ruholloh Khomeini. Individuals lose themselves in the spectacle of the crowd, effectively surrendering their meaning-giving capacity. Then there is the spectacle of spectacles, Chairman Mao, to whom more than a billion people surrendered their private wills, dressing like him and living by the sayings of his little red book.

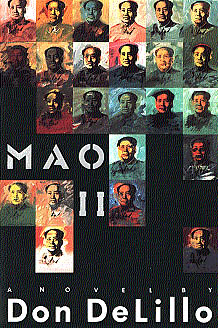

Mao II, the work by Andy Warhol, is an ironic take on Chairman Mao, mass-producing his image and doing precisely what Bill suggests—draining the man of meaning. Mao II, the novel by Don DeLillo, may also be ironic, but in the opposite direction. It is about a book that resists mass production by remaining in storage on the author’s shelf, but WE read this novel because DeLillo has surrendered it to the capitalist system of mass production, distribution and consumption that characterizes the global publishing industry.

I have no idea what to make of that.