My wife is an active alumnus of a summer camp in Longford Mills on the northeastern shore of Lake Couchiching. Every fall, staff, alumni, and friends of the camp gather for a weekend of work and fun. The object is to close down the camp for the winter, taking in docks, storing boats and equipment, cleaning out cabins, clearing out dead wood and chopping it. One of my chores was to rake leaves. There are a lot of leaves in a forest, which means the raking takes a long time. It’s repetitive and, as happens with me and repetitive tasks, my mind starts to wander. I had been reading a book by Mircea Eliade the night before and that helped fuel my wandering mind. Actually, my mind never really wanders; it’s more like a NASCAR race with a pileup against a wall.

In the inside lane, we had this line of thought: I was thinking of my own camp experience as a kid. I didn’t go to Camp Couchiching; I went to a rival camp which wasn’t half as cushy as this camp (we slept in tents instead of in cabins). In particular, I was thinking of how oblivious I had been to the contributions that other people made to my camping experience. That’s the way it is for kids. Things seem to happen as if by magic. Meanwhile grownups, many of whom we may never know or meet, are busy working in the background to ensure that children—not necessarily our children—can have the best possible experience. Children, especially when they’re young, live in a kind of pleasant fog. As they get older, they become increasingly aware that their experiences belong to a wider social world. They know there are counsellors and program directors and a camp director, but it isn’t until they are much older that they learn about the board of directors and affiliations with the wider world, which includes a large group of volunteers and hangers-on who are simply glad to lend a hand from time to time. There is a sense in which we can say that, as campers age, they experience a demystification of camp. The pleasant fog evaporates and they become aware of themselves as individuals within a larger matrix.

The Wizard’s Levers

We talk a lot about demystification. Although Barthes said it was an outmoded strategy two generations ago, it may well be a necessary stage in the postmodern approach to all our social institutions. I have written about it on this blog in reference to religion, especially (surprise, surprise) when I was studying at a seminary. Certainly atheists love to engage in religious demystification. They’re like Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz, pulling aside the curtain to reveal that the pyrotechnics aren’t magic, but the manipulations of a burnt-out vaudeville fraud. More recently, I’ve been tracking the demystification of the printed word. The appearance of ereaders and the development of digital formats has accelerated a trend at work in Western culture since the invention of the printing press: the gradual erosion of the printed word as a magical bearer of meaning. Call it the secularization of print. Once, books were the repositories of sacred wisdom. Even as they became profane objects, like novels, texts, and non-fiction discussions of issues in our world, they retained an aura of authority. If a person quoted a book to support his own position, some of that authority passed from the book to that person’s lips. The rise of the ebook has merely made obvious, like the curtain pulled back from the wizard, that authority does not live in the print; it has nothing to do with the weight of the paper; nor the art of the cover; nor the display in the bookstore. Just as it has been unequivocally demonstrated that the Bible is the result of a highly fallible and utterly human process, so too the revolution in digital publishing has made it clear that books more generally have no magical authority. Books are the accumulation of words from highly fallible people who burp and fart just like you and me. They have become utterly demystified.

The problem is that we don’t like this state of affairs. We liked it better when we could appeal to the Bible as if it would settle everything for us. We liked it better when we could take up a book and cite it as if an aphorism was all it took to win an argument. We feel nostalgia for the days before demystification, just as I felt nostalgia, while raking leaves, for a time in my childhood when camp magically appeared each year just for me.

The Hostile Tone of Public Conversation

There is another problem, too, and that has to do with tone. I note a common tone in the quality of conversations that play out in both religion and publishing. At best, it is patronizing. More often, it is hostile and divisive. So, for example, a good number of atheists find religious people frustrating. Science, empiricism, rational thought. All of these modern approaches thoroughly skewer religious claims. Religious types don’t live in the real world; they’re ruining it for the rest of us by poisoning public discourse, sticking their noses in places they don’t belong. At the same, early adopters in the digital world look at traditional publishing houses and call them Luddites. People who prefer paper books are fetishists or are too ossified to adapt.

Imagine if the volunteers at the camp work weekend assembled and passed a resolution to adopt such a tone. Be it resolved: campers who refuse to see all that goes on behind the scenes will be ridiculed next summer; they will be taunted and systematically told they lack insight; and they will be forced to spend time doing some of that work instead of swimming with their friends and roasting marshmallows by the fire. But we never make such a resolution, do we? We are happy to stand behind the curtain with the wizard and keep out of sight. The reason, I think, is that nothing hinges on forcing the demystification. There is nothing of our personal identity at stake in what we do. Our egos do not demand of us that we go to the camp next summer and tell all the campers what we did the previous fall, how we require their acknowledgment. On the contrary, the tone of the weekend is one of generosity. We are present for them, whoever they may be, and not for ourselves.

My analogy is inexact. It seems to imply that I think of those who resist demystification as childlike; religious people are intellectually naïve; defenders of traditional publishing are just being overly nostalgic. This is a limitation of my analogy, not of my argument. I would suggest that the same generosity of tone ought to seep into our more politicized conversations. If we choose to engage the modern with demystifying approaches, we might inquire first as to our own motives. Do we do this because we believe there is some neutral social benefit to be had? Or are we more concerned with private personal interests?

Eliade & Rites of Initiation

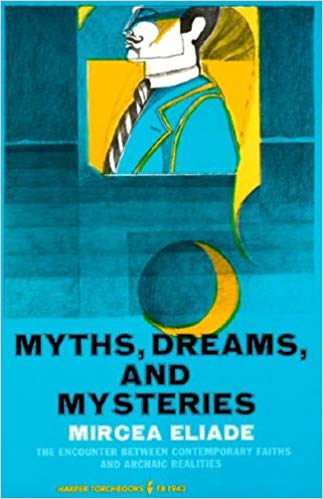

This takes me to Eliade. The book I was reading was Myths, Dreams, and Mysteries: The Encounter Between Contemporary Faiths and Archaic Realities. Eliade was a Romanian pioneer of comparative religion who wrote from the 1930′s to the 1960′s. He was interested in the way insights from other disciplines, like sociology, psychology and anthropology, could be leveraged to illuminate religious concerns. He felt it important to study the religious practices of non-Western (especially indigenous) cultures, anticipating an increasingly globalized culture in which the West would be forced into close proximity with the Other. In his view, the West had a choice in how it handled these encounters, but that choice was contingent upon the extent to which it educated itself and empathized with those it viewed as Other. Following the work of anthropologists like Margaret Mead, Eliade gave a great deal of attention to rites of initiation, both into adulthood and into secret societies.

One could argue that summer camp is a Western appropriation of the rites of initiation which appear almost universally in indigenous cultures. A rite of initiation is an inherently demystifying process. It introduces the novitiate into the secrets of the group. He becomes the bearer of a fuller knowledge which he in turn transmits to future novitiates. Campers discover that there are older people who do things in off-season gatherings to help maintain the camp for the following year. In succeeding years, many of these campers, as older people, do things in off-season gatherings, and so it goes. The curious thing is that the precise content of the secrets doesn’t matter (it could be leaf-raking or log-splitting). From the perspective of a scholar in comparative religion, what matters is the discovery that the rite of initiation functions identically across cultures. Its purpose is to establish membership in the group. It’s purpose is to affirm identity, not to affirm a specific knowledge except as that knowledge contributes to identity.

Because I have no great stake in the knowledge of camping, it is easy for me to detach myself from its mysteries. That’s why it is easy for me to use the initiation rite of the summer camp as an illustration. It might not be so easy if I were an atheist. I might be more attached to the particular details of atheism, so much so that I might miss the fact that the ability to recite the particular details of atheism is itself part of a rite of initiation. Similarly, a Republican has her talking points. And a Progressive Christian has his apologetics. And so on. The attachment to content is, in part, an affirmation of social identity. This is my tribe! The irony, at least for the atheist, is that the rite of initiation to establish group membership has a religious provenance.

Death of the Self and Rebirth

Eliade observes the basic schema of the ritual: it involves the death of the old self and the rebirth of the new. An example from Western culture: hazings are rituals designed to destroy the neophyte’s former identity. They are symbolic human sacrifices. Sometimes, the group takes that schema literally, engaging in actual human sacrifice or in ritual killings. For example, some modern gangs demand the commission of a murder as the cost of initiation.

It could be argued that the harsh tone of debate in much of contemporary Western discourse follows the same schema and has acquired its edge precisely because it seeks to fulfill a symbolic sacrifice. The atheist cannot truly claim membership within the tribe unless he emulates the kind of bloodletting that a Christopher Hitchens achieves when he sets upon a hapless Christian or Muslim fundamentalist. We witness the same ferocity in contemporary political exchanges, in debates between copyright law-and-order types and “free culture” advocates, and most recently in the kind of salvos between traditional print publishers and advocates of the self-publishing ebook market. In fact, pick just about any cause that receives play in our media and you are likely to find Eliade’s schema lying below the surface. We daily affirm our group affiliations through the ritual slaying of our opponents or through ordeals in which we die to our old selves and rise again to the new.

Nowadays, our instrument of choice may be the demystifying power of science and rationalism, but we have never been so religious.