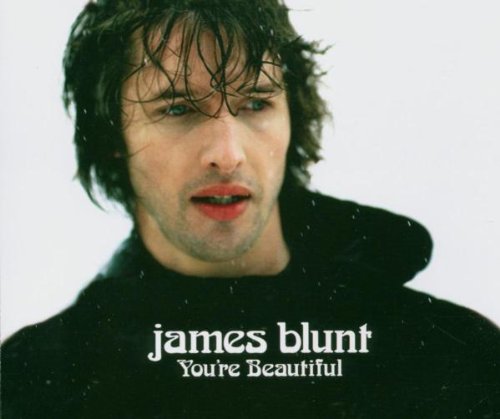

On Sunday, my daughter had her first confirmation class. The minister, to his credit, asked the kids to bring along a song—whatever they happened to be listening to—so that he could get a feel for where they are in their lives. My daughter asked if I could burn “You’re Beautiful” to a CD for her. I’ve heard the song on the radio; maybe you have too. James Blunt sings about love and heartache and sounds like one of those sensitive guys—you know the ones—the guys all the girls fawn over—the guys parents would love their daughters to go out with. Then I listened to the song. Wait a second. Did I just hear the word “fuck?” I looked up the lyrics and discovered that there is a radio (i.e. sanitized) cover & a CD cover. I pointed this out to my daughter and she confessed that she doesn’t really listen to the lyrics; she just likes the feel of the song and hadn’t really noticed before. OK, I said; I just wanted to be sure she knew. So she took her song with the word “fuck” to church.

I don’t know about this word “fuck.” We live in conservative times when some people (whose identity always seems obscure) feel compelled to protect us from our baser instincts—as if we, left to our own devices, would naturally stray into a chaotic way of living where words like “fuck” would assault our sensibilities at every turn.

In fact, the word “fuck” has been with us for some time. Certainly Henry Miller made much of it in The Tropic of Cancer. George Carlin has celebrated its use in connection with its 6 lesser siblings. More recently, David Eggers has expressed ambivalent feelings about its use, acknowledging that it crops up in his conversation, but wondering whether it really should be used as a verb. I seem to recall that it appears in Shakespeare in a backhanded way—in one of the histories (maybe Henry V), a French woman asks why the English talk so much about the foot. In my copy of Young’s Analytical Concordance to the Bible, I see no instances of “fuck,” but who can doubt that “fucking” is precisely what David was doing to Bathsheba? In fact, the Bible is chock full of fucking.

In church, more than anyplace else, one encounters a sometimes stifling sense of propriety. Things must be done just so; words spoken in just this way, heads bowed at just this angle, expressions revealing just this much awe or reverence—as if the experience of church is one great magic incantation. If we don’t get everything right, then the spell will be broken and God—just another djinn in the bottle—will refuse to pop up in our midst because we rubbed the bottle the wrong way. This is complicated by the fact that different people have different notions of “proper.” Some think it is proper for people to burst into spontaneous applause if they hear music that stirs them: they say that it is not just the music, but also the spirit, which moves them; others are aghast at applause and feel this destroys the contemplative atmosphere of worship. Some think it would be fun to have a drum kit, rhythm guitar and a couple of doo-wah backup singers shaking tambourines; others can’t imagine worship without a big pipe organ shaking the foundations. These debates began long before I was born and, no doubt, will go on long after I’ve turned to dust. Between you and me, I couldn’t give a rat’s ass—oops, there I go with the language—for the propriety of worship. God is there. Period. No special words needed. No candles necessary. More often than not, I suspect God is there in spite of us. If you want to create the perfect mood, then do it alone. I don’t write this flippantly; there are times when each one of us needs to approach our spiritual centre in privacy. But worship in church is celebration as a community, and, since we are talking about the revelation of universal truths here, there is one universal truth you can stake your life on—living in community is a messy business. People come together from widely divergent experiences, bearing all sorts of fears and cares, hoping with impossible, often contradictory, expectations. If each person holds to private experiences, personal fears, and unexpressed hopes as the measure of propriety, then everybody will leave the sanctuary feeling disappointed.

In our places of worship, more than anyplace else, we encounter a hunger for meaning. Our practices around the word “fuck” and other taboo incantations reveal much about how we think, or fail to think, about what it means to mean something. Sometimes, to avoid printing the word, we print “f**k” instead, or, in the case of radio and television, we beep over it. sometimes, we encounter people who consider a word, like God, too important to trivialize in its printed form, and so they print “G—d” instead, capitalized of course, as if God might strike them dead for printing the label in full.

Fuck and God are not magic incantations; they are signs—just as fk and G—d are signs. Fuck and fk share identical referents, as do God and G—d. The meaning does not reside in the squiggles that appear on the screen or on the paper, nor does it reside in the auricular sensations we experience when somebody speaks aloud these words. Meaning is an act. It is an act of communication between two or more people. And communication only happens in community—that messy place where worship also happens. Meanings can only happen if people already find themselves embedded in the language which grounds their utterances. As babies, we are baptized into language. It is a full immersion, with words of parents and older siblings flowing all around us, prompting us to respond with gurglings and cooings as we grow towards articulate speech. Later, it becomes a communion, as we participate fully in a lifelong conversation which is both meaningful and meaning-filled.

I wonder, too, about our notions of propriety when we approach God. The propriety of our approach may be good for us; we may be more receptive to God’s presence if we feel settled. But does it really matter to God? Will God be any less present to us if we are upset or anxious or just pissed off? Will God turn and run if we get angry and swear? I wonder what Jesus really said in the Garden of Gethsemane when he realized that he was done for. Did the gospel writers sanitize things for us just the way censors compel singers like James Blunt to produce sanitized lyrics for radio? Whatever one’s theology says about the humanity of Jesus, I think when you are about to have nails driven through your hands and feet, you might say something like: “God, what the fuck were you thinking?” On a couple of occasions in my life, I have found myself in crisis. I know, in retrospect, that God was very much present to me in those moments, not because I got down on my knees and lit a candle and hummed a few bars from a nice hymn, but because I got raging mad and told God where to shove the universe. This doesn’t exactly make for poetic testimony at some mealy-mouthed Bible study, but, well … it’s my testimony … God only ever became real to me when I trusted enough to unburden myself of my real feelings. At that moment, then, a new kind of conversation started. Now, I really understand what the exegetes say about the Aramaic word “abba”—it is closer to “daddy” than “father.” I don’t exactly refer to God as my daddy, but God and I are most definitely on more familiar terms these days.

As for my daughter, she played the song at church. Nobody noticed the lyrics, or if they did, they didn’t seem to mind. Good for them. Good for her.