It isn’t exactly news to point out that publishing is in crisis. Now that digital text can be delivered in a format which offers a viable substitute for the physical book, there are fears that the publishing industry will experience an upheaval of biblical proportions. Observers draw an obvious comparison to the music industry, which has spent nearly a generation coping with an analogous upheaval thanks to the advent of digital audio. But I say unto you: a more apt comparison can be found in the experience of religion, whose institutions have been in crisis far longer than EMI or BMG.

I believe—oh yes I do—I believe the comparison is apt because, unlike big music labels, whose primary challenges arise from changes in technology, publishers face challenges which go to the very foundations of their beliefs. In our secular world, the credo has been demystified. The publisher’s loss of faith is more than merely analogous to the experience of organized religion; the crisis of one is the crisis of the other.

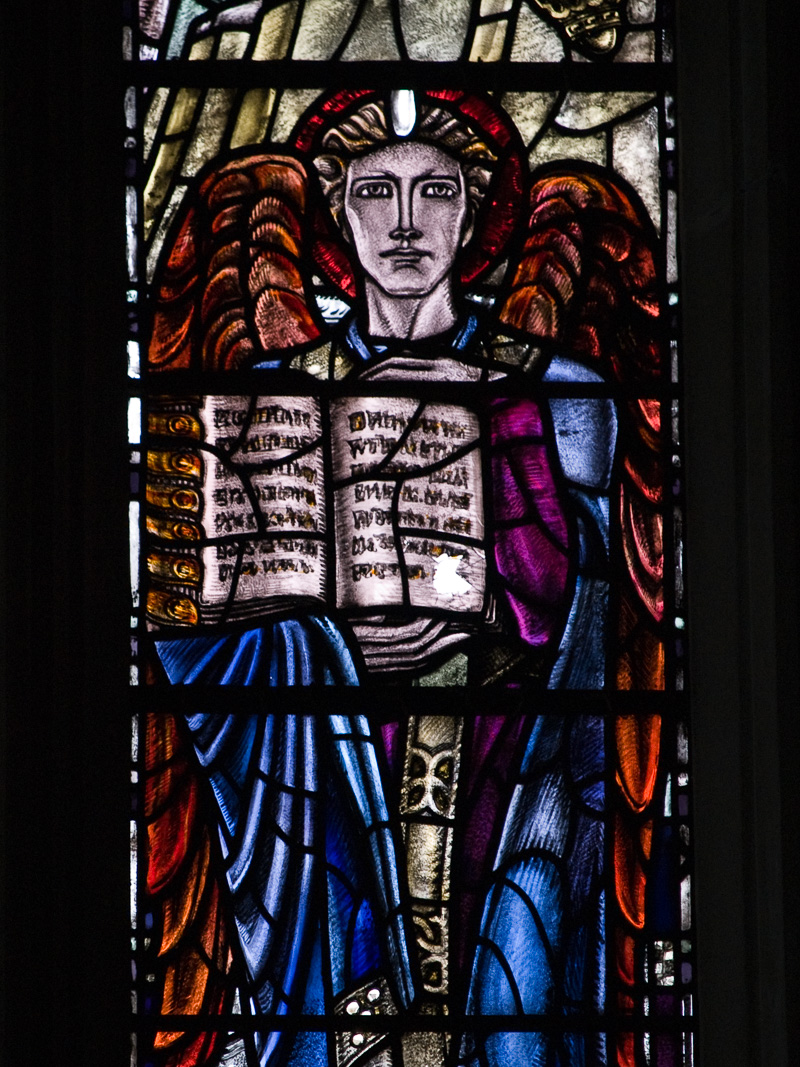

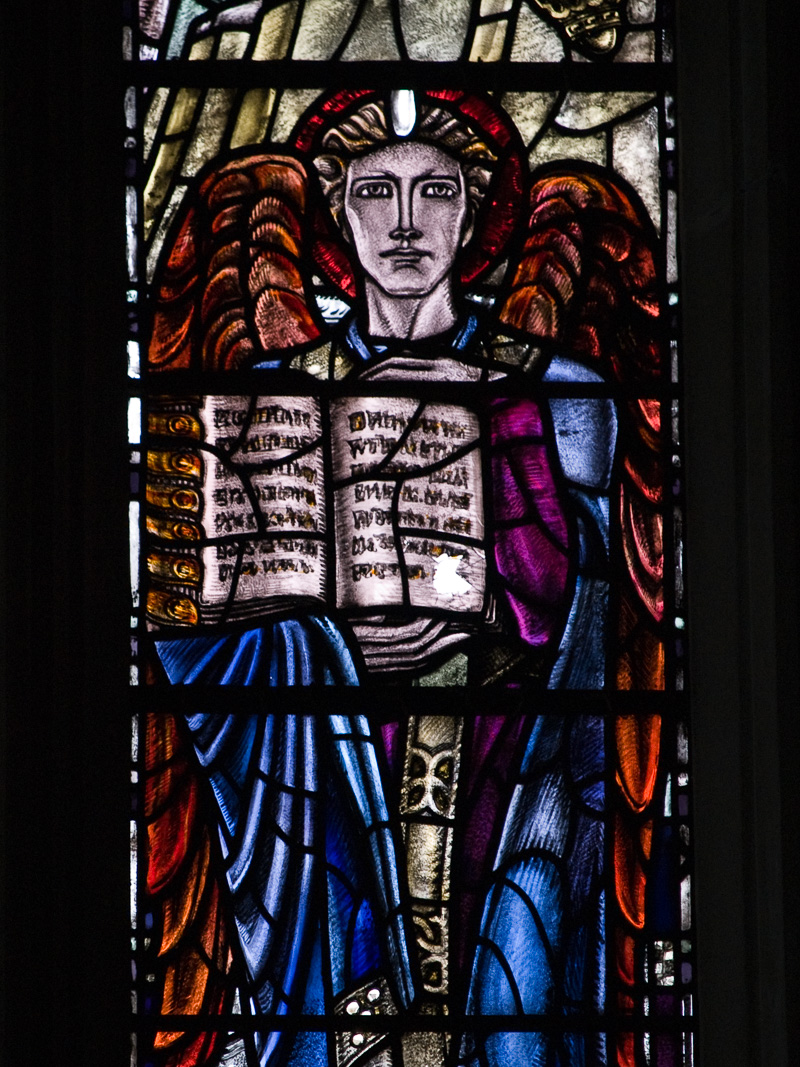

People of the Book

As a term of respect, the people of Islam speak of the children of Abraham and the followers of Jesus as “the people of the book.” Western religions tell us our names are written in the Book of Life while both Egyptians and Tibetans have a Book of the Dead. The collected wisdom of Moses, the first of our prophets, is borne in the Torah which itself is borne in the Ark. When Christians read from the Bible during worship, they often conclude with: “the Word of God.” Jesus is the Word made flesh. Logos. Whatever else you might think (or not) of Johannine theology, one thing is certain: unwittingly or otherwise, the Gospel of John entrenched in our cultural consciousness a notion of the book as a form of embodiment. Just as God could take His divine wisdom and set it in a Holy Book, so we could take our earthbound wisdom, the numinous drippings of our souls, and fix it to the page to comfort and guide future generations. With the book, we could defy death.

Gutenberg Changed Nothing

A scribal tradition delivered to us our earliest scriptures across two thousand years, a succession of textual reincarnations down to the age of Gutenberg. There is a debate about whether the digital revolution will be as historically significant to our age as the Gutenberg revolution to the Reformation. While I prefer not to gamble, if forced to it, I would wager that five hundred years from now historians will treat Gutenberg as a pop gun when compared to the ASCII nuclear explosion that has engulfed our age. Here’s why: Gutenberg did nothing to unseat our fundamental conception of the book as an embodiment. His printing press preserved the mystical sense that within the tactile covers of a book there lay something of its author’s spirit. Digital text, on the other hand, thoroughly disembodies our words and therefore challenges how we think even about thinking itself. (At the same time, I am cognizant of the irony that the word digital implies the very tactile quality which the digital revolution undermines.)

Demystification and Authority

In a moment of crisis, the publisher asks: What is a book? This echoes the long-standing question from religious thinkers: What is the source of our authority? For more than two generations, academic theologians have applied historical, text, redaction, and form criticism in an expanding toolkit of approaches to biblical scholarship which reveal the all-too-human process by which we have received our authoritative texts. And the academy is merely one of countless agents in the demystification of religious authority. The dominance of a secular science, the sheer volume at which our popular culture assaults the senses, the global reach of our media, the dislocation of labour brought about by deregulated markets, the commoditization of everything from water to reproduction, all these challenge the authority of the Book.

The threats to publishing cut across the same lines as those to religious authority. Independent booksellers fold as fast as suburban churches. Younger customers have been drawn away from reading by distractions like TV and movies, video games and social networks. Big box stores can resist the trends (incidentally contributing to the demise of independent booksellers) but they can’t compete with behemoths like Amazon. When even the old fogies start to worship on Amazon, places like Saddleback and Willowcreek, Chapters/Indigo and Borders are screwed. People have lost the faith.

Panic of the Faithful

Meanwhile the clergy are scrambling to find creative ways to slow the exodus. Fr Cory Doctorow embraces DRM-free text and gives everything away. Sister Margaret Atwood sets up a twitter account and takes her religion to the digital masses. A clueless orthodoxy screeches that our salvation lies in the cult of copyright. All of the many postures that our clerics assume—the scurrying, the expostulations, the anger, the tears, oh the wailing and gnashing of teeth—all of it can be interpreted as expressions of grief.

The book may not be dead, but its cultural significance expired last Friday and there hasn’t been a resurrection yet. Don’t hold your breath. Demystification is like “getting” an optical illusion. Once you understand the visual trick, you can’t reset your brain to an earlier time when you couldn’t see the illusion. Henceforth, you will always see it. In the same way, once the “magic” of the book disappears, we can never revisit a naive pre-digital state any more than a chick can crawl back inside an egg.

We may have nostalgia for that feeling of excitement that comes from cracking open a new book, the touch of the paper, the smell of glue on the binding, the anticipation of discovering new worlds within its covers. But there will never be a time henceforth when text cannot be digital. More to the point, there will never be a time henceforth when text is not demystified. This is a fact of our circumstances and, unless we choose to live in denial, we must acknowledge those circumstances and get on with it.

Requiescat in Pace