In May of 1982 I received a letter from the Royal Conservatory of Music informing me that I had passed my piano exam. Since I had already completed all the course work (History, Harmony, Counterpoint, etc.), that meant that I was officially an Associate of the Royal Conservatory of Music and could put the letters A.R.C.T. after my name. The first thing I did was phone all the music schools where I’d set up auditions and cancelled them. Screw it! I wasn’t going to be a musician; I was going to do something practical with my life. And so, in September, I found myself at Victoria College studying things like English Romanticism, Elizabethan Drama, and Medieval Latin Poetry. I have an odd view of what counts as practical in life. A couple weeks into my program of higher learning, news broke that Glenn Gould had suffered a stroke. A week later, on October 4th, 1982, his father removed him from life support and he was pronounced dead.

As with thousands of other kids who passed through the conservatory program, Glenn Gould was an enormous presence lurking in the background. I was one of those nerdy kids who collected vinyl. I bought everything by David Bowie, Pink Floyd, Brian Eno … and Glenn Gould. I had both releases of the Goldberg Variations, both volumes of the Well-Tempered Clavier, Partitas, Haydn Sonatas, Mozart Sonatas. I even allowed for a recording of Brahms piano music, although it struck me then (and now) as strangely hollow. Even while he was alive, stories of his eccentricities had become the stuff of legends. During my piano lessons, Glenn Gould was invariably a reference point for conversations about technique: how close to the keys; how rotten the posture; how loud to hum while playing.

As a kid taking music lessons in Toronto during the 70’s & 80’s, I can’t honestly say that I ever rubbed shoulders with Glenn Gould. But there was one point of intersection between our lives. That was the piano tuner, Verne Edquist. My parents persuaded him to look after our Gerhard Heintzman upright grand piano in the years leading up to my final conservatory exam. I would sit in the room while he tuned the piano. He was a direct man and didn’t mind telling me what he thought of our piano. Years later, when my wife and I settled into a house of our own, my parents gave us the Heintzman and bought themselves a proper grand piano. I was annoyed they didn’t keep the Heintzman and buy us the grand, but I wasn’t in any position to argue with them. Ultimately, we sold the piano to one of Gerhard Heintzman’s great grandchildren and bought a Yamaha Avant Grand. Since the Avant Grand is digital, it never needs to be tuned, which means I’ll never have the kind of relationship Gould had with Mr. Edquist.

In 1982, I abandoned my musical education and it seems, in retrospect, like an act of self-sabotage. I was too something-or-other to do drugs or get nipple rings; the worst thing I could think to do to myself was to stop playing the piano. But decisions like that are never once-and-for-all-time. Last year, I started taking a master class for “mature” pianists who want to brush up on their performance skills. We meet at U. of T.’s Faculty of Music, that school I might have attended if not for my sudden fit of practicality. One of my pet projects is to work up Bach’s Goldberg Variations. It’s on my musical bucket list along with a handful of other big piano works. We’ll see how it goes.

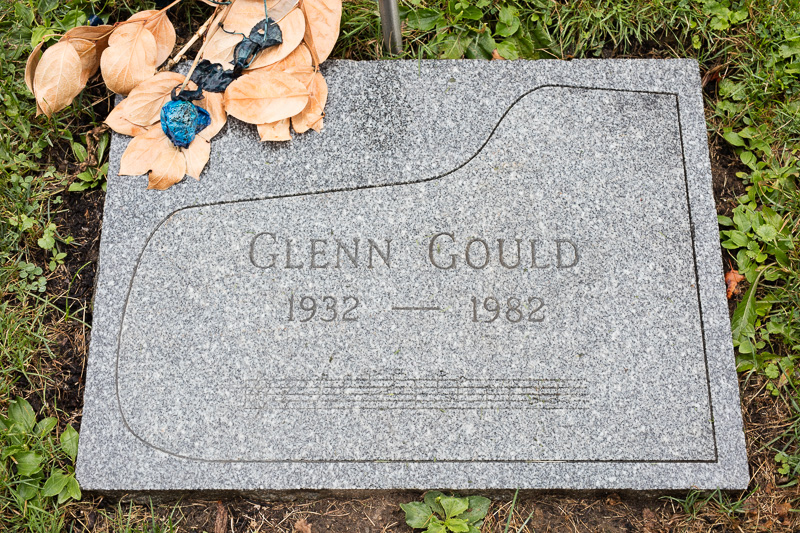

It’s astonishing how, a generation after his death, Glenn Gould remains an enormous presence lurking in the background. And so I decided (finally) to pay my respects. His grave is in Mount Pleasant Cemetery on the east side of Mount Pleasant Road. It’s a modest marker in section 38: his name, his dates, and the opening passage from the Aria of the Goldberg Variations. I don’t know if my visit will give me inspiration or determination or emotional fortitude or what. Probably not. After all, his music isn’t there, at that site, in that plot of ground. It’s here and here and here, in the hearts and minds of the thousands like me who hold it with us wherever we are.