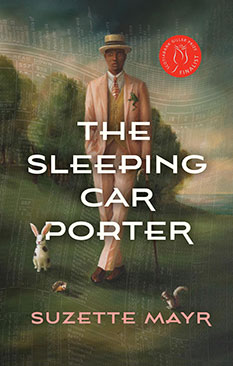

The year is 1929 and Baxter is a young Black man working as a porter on Canada’s rail lines. Although, for many men in Baxter’s position, work as a porter is the best they can expect from life, Baxter aspires to more. For him, work as a porter is a means to an end; he hopes to save enough for tuition to Montreal’s McGill Dental School. (As an aside, I wonder if this isn’t a sly tip of the hat to Frantz Fanon who originally hoped to become a dentist before veering off into psychiatry and writing his works of political philosophy.) Some time ago, Baxter found a discarded manual of dentistry and, ever since, he has been obsessed with the idea of dentistry, perhaps developing and patenting dental prosthetics, maybe growing rich on the oral misery of others. True to his vocation, Baxter subjects every personal encounter to an assessment of dental health. To date, his work as a sleeping car porter has netted him $967; tuition is $1,068. He has $101 to go.

In addition to teeth, Baxter has several other obsessions. One is a love of science fiction, reading issues of Weird Tales and, as time allows, dipping into a volume about adventurous Egyptologists called The Scarab of Jupiter which he carries with him in his satchel. It’s easy to see why a young Black man would be drawn to science fiction: it carves out an imaginative space where anything is possible. A second obsession is his concern for demerit points. Ten more demerits and the railway will summarily dismiss him and that will effectively put an end to his dental school savings plan. While demerits can come about for obvious reasons (theft, drunkenness, assaulting passengers), most happen as a consequence of passenger complaints about matters that are either arbitrary or lie utterly outside the porter’s control. Even so, without the advocacy of union representation, porters have no recourse and management automatically believes the passengers. The only way to avoid demerits is to be always on call, always smiling, always obsequious, always the diplomat. In other words, the porter has to be superhuman. Baxter copes with the demands by imagining he’s a robot from one of his science fiction stories.

It turns out Baxter has another obsession. He finds a homoerotic postcard on the floor in the men’s washroom and pockets it. In the real world, the role of porter affords little time to act on his desire. And so, apart from rare fleeting encounters, much of his desire works its way into his rich imaginative life, where scarab beetles on Jupiter vie for his attention with memories of alleyway trysts. We feel the danger of this third obsession. In his interactions with the passengers, maybe he’ll misread the cues and unintentionally out himself. Management would inevitably hear about it and Baxter would find himself unable to get work in this or any other town across the country.

Apart from a brief introductory chapter, the novel unfolds on a single run from Montreal to Vancouver. Baxter makes up beds, fetches towels, shines shoes, delivers glasses of water, cleans trampled crackers from the carpet, entertains a bored child, and answers countless inane questions. The run takes four days and, for most of that time, Baxter must be on call. He knows that, by the time the train rolls into Vancouver, he’ll be physically spent. He thinks of his sleeper car as “his luxurious prison”.

Suzette Mayr never strays from the train and so we, as readers, begin to share in Baxter’s feelings of claustrophobia. This is a risky strategy on Mayr’s part insofar as the reader might grow impatient and want to stretch their arms, in a manner of speaking, when passengers debark at stops along the way. But Mayr is equal to the risk, writing in crisp, entertaining prose that holds the reader’s attention. She is particularly adept at capturing the countless interactions Baxter must negotiate as he avoids demerits while still answering what we today would call microaggressions. Most of the passengers behave in ways that are not overtly racist, and yet racism lurks underneath the interactions and, in the context of a train ride, we begin to share in Baxter’s tightly constrained world. Yes ma’am. No ma’am. Right away sir. Taken together with his life as a closeted gay man, he has barely air to breathe.

Somewhere between Calgary and Banff, the train wheezes to a stop. A mudslide has covered the tracks ahead and they cannot move until the tracks are cleared. When it becomes apparent that this will be more than a minor delay, emotions rise. Passengers become more anxious and, at least for some, that plays out in more aggressive behaviour. They treat Baxter as the scapegoat for their frustrations, as if he was somehow responsible for the mudslide. Eventually, the conductor permits the passengers to debark and, after that, even the porters. The porters and waiters are expected to entertain the passengers in the wilds of the great outdoors, and there is some incredulity when Baxter advises that he cannot dance.

In a way, the mudslide episode functions as a release. It literally outs everyone. The passengers abandon the close spaces of their sleeping car luxury for the wide spaces of the Rocky foothills. And, at least while the porters are putting on their show, they break for a time from their usual strictures. Baxter even has a chance to engage in a brief dalliance with a passenger who has been making overtures since almost the outset. And then, of course, they must board the train and resume their old roles as they roll westward to their certain destination.

The result is a beautiful and tightly structured novel that brings to life the constraints drawn around the lives of Black men, especially gay Black men, trying to make their way in Canada’s predominantly white society nearly a century ago.