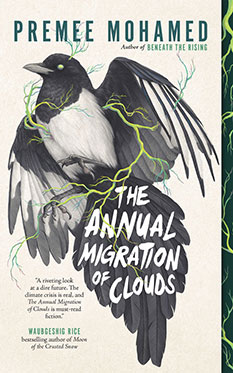

I bought Premee Mohamed’s second novel at the ECW Press booth at Word On The Street. A girl was holding a copy of Waubgeshig Rice’s Moon of the Crusted Snow and I told her that I’d enjoyed it. The ECW girl standing on the other side of the table said: well, if you like that, then you’ll like this, almost like an Amazon recommendation algorithm. I see the similarity. Both novellas unfold against the backdrop of an unspecified catastrophe that has brought about the collapse of civilization as we know it. In both, there are hints that a pathogen is implicated although we don’t know if it’s the cause of collapse or simply something opportunistic that takes advantage of this new state of affairs. In Mohamed’s story, she names the pathogen. It is Cad, short for Cadastrulamyces, a parasitic infection that is described as a “heritable symbiont” contracted through the placenta in utero.

I can also draw a comparison to another Canadian writer of post-apocalyptic visions, William Gibson. In a passage reminiscent of Gibson’s 2014 novel, The Peripheral, we learn: “It was not instantaneous, the “end of the world,” the way it is in nightmares. The sky didn’t tear open around an asteroid, the earth didn’t swallow us up. And of course, the world did not end at the same time for everyone. No one back then would have been able to say: This is the day our world ended. Or even: This is the year.” Gibson captures the “not with a bang but a whimper” civilizational collapse with his idea of “the jackpot” which lurks in the background of The Peripheral: “No comets crashing, nothing you could really call a nuclear war. Just everything else, tangled in the changing climate: droughts, water shortages, crop failures, honeybees gone like they almost were now, collapse of other keystone species, every last alpha predator gone, antibiotics doing even less than they already did, diseases that were never quite the one big pandemic but big enough to be historic events in themselves.” If I were inclined to write obscure jokes, I’d say we live in the aftermath of a lost literary world where all the plots involving catastrophic events got used up and left us with the less dramatic but more probable slow creep of human stupidity as our basic plot premise.

Here, the main character, Reid Graham, has won a place at a prestigious university. However, because the university represents the last vestiges of a lost world, no one is certain if it actually exists. Presciently, Mohamed tells us that Reid won her place by writing an essay about reproductive rights, or more to the point, about the gradual erosion of reproductive rights which she cites as one small part of a cascading social collapse that, like Gibson’s “jackpot”, delivers her world to its current historic moment. While Reid’s community is benign, nevertheless it is shot through with ignorance and a general suspicion of change.

For most of the novella, we witness Reid in conflict with her mother or, more properly, with her own feelings of guilt and with the fears she has internalized. To dissuade Reid from making the journey to the university, Reid’s mother goes so far as to promote a conspiracy theory. She claims that the teacher who administers the essay applications in fact never submits them, faking acceptance letters and allowing the successful applicants to wander off and die in the wilderness. To address her feelings of guilt, Reid goes on a boar hunt, hoping to provide her mother with enough resources to compensate for abandoning the woman.

Add this to your collection of post-apocalyptic pandemic stories. Taken together, these stories reveal a curious trend: a strange correspondence between the anti-vaxx, anti-mask conspiracy theorists we encounter in the world of Covid-19, and the characters in dystopian fiction. It’s almost as if writers today are hiring these people to workshop roles for soon-to-be-released novels about a world in the grips of a contagious pathogen.