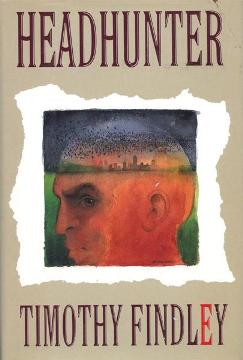

I have a special pile of books, purchased with the best of intentions, which nevertheless go unread. What lurks in the background is, perhaps, a species of gluttony. I want to read everything. I want to swallow it whole, digest it, ruminate until I pass it into my second stomach, break it down and draw all those words through my literary villi and into my bloodstream. And so, driven by my bookish hunger, I step into a bookstore and take up this, this, and this, ignoring the fact that I am mortal after all and haven’t an infinite stretch of reading time before me. One of those books buried in my special pile is Timothy Findley’s rather long-winded novel, Headhunter. Cracking it open, a receipt and courtesy bookmark fall out. It appears I purchased it as overstock in 1996 at Edwards Books on Queen Street West. Edwards Books no longer exists. Nor does Timothy Findley.

The first intimation that I might one day get around to Headhunter came 10 years ago while reading Imagining Toronto by Amy Lavender Harris. Harris teaches geography at York University and has compiled a wonderful literary geography of Toronto. Headhunter gets a mention in a section on ravines. Lilah, one of the principal characters in Headhunter, is a schizophrenic woman who recalls how her mother was murdered in the ravine below the Glen Road Bridge. Because I frequent the trail below the Glen Road Bridge and occasionally photograph graffiti underneath that bridge where there are fire pits and encampments, the reference solidified my resolve to read the novel. After all, if I could finish Margaret Atwood’s equally long-winded The Blind Assassin which features another stretch of the same ravine, then there is no reason for me to put off Timothy Findley’s novel. But putting things off is my special power.

Here I sit, more than a quarter of a century after purchasing the book, and by accident I discover that it would make a good addition to my plague-related reading list. At last I have the motivation I need to read the novel once and for all:

Lilah Kemp, the schizophrenic mentioned above, is sitting in the Toronto Reference Library reading Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness when she notices that Kurtz has escaped from the novel on page 92 and is free to roam in the wider world. Whatever he might be inside the novel, out here, Kurtz is a psychiatrist and director of the Parkin Institute of Psychiatry (based loosely on what was then called the Clarke Institute of Psychiatry) and he keeps offices on the topmost floor of a building based loosely on the Brutalist monstrosity that sits on the northeast corner of College & Spadina. There is something about the esteemed psychiatrist’s practice that takes him into the darker reaches of the human psyche. For those familiar with Conrad’s novel, it should come as no surprise that a new psychiatrist named Marlow joins the staff of the Parkin and he pushes upstream (or whatever the psychiatric equivalent) into those darker reaches to figure out what precisely Kurtz is doing there.

Findley’s interest in mental illness is engaging enough, but the novel’s chief interest, at least in light of current events, lies in the fact that the novel unfolds against the backdrop of a plague called sturnusemia. Here is how he introduces it (bear in mind that he was writing 30 years ago):

The blessing of winter was that it reduced the number of deaths from sturnusemia. To date, only fifty-five people in Toronto had died of it—less than in cities of greater size, but more than any other city in Canada. The deaths had reached their peak in July, when eight people died in one week. This had been during the height of the annual heat wave. Now, the coming spring—though some weeks away—was dreaded because of the expected influx of birds which carried the disease—starlings, mostly—whose Latin tag had given the plague its name.

So-called D-Squads make regular sweeps through city neighbourhoods, spraying all the trees with an exfoliant so the birds are exposed and can easily be exterminated. If household pets roam free, the D-Squads shoot them on sight to ensure that the disease doesn’t pass from birds to pets to humans. People wear masks, not so much to protect themselves from the disease (which seems to spread through direct contact with birds) as to protect themselves from the toxic spraying. Alongside sturnusemia, Lilah identifies a secondary plague of non-belief: This is not happening, people said—this is not plausible. We will wait for an acceptable explanation. Sounds vaguely familiar, no?

Later, we have a fleeting introduction to a man named Adam Smith. A renowned plastic surgeon consults Kurtz and they share talk of a mutual client, a paranoiac who goes under the surgeon’s knife, gradually erasing his identity and, with it, his name. He becomes Adam Smith-Jones, then Smith Jones, then simply patient X. The mention seems incidental and so we are apt to ignore it in the face of more salacious intrigue, most notably a child pornography ring to titillate the Rosedale elite. Nevertheless, Smith Jones re-emerges 350 pages later as Marlow pores over Kurtz’s patient notes and discovers a hand-written statement by the patient he has come to know as The Paranoid Civil Servant.

Smith Jones writes that he has uncovered a plot at the highest levels of government aimed at duping the public as to the true nature of the pandemic. He doesn’t deny the existence of a pandemic, but he does deny that it has anything to do with birds. All of that, the spraying, the D-Squads, the animal exterminations. All of that is just show to deflect our attention from the true situation. He writes: “What has happened is this: as a result of an unpublicized experiment with genetic engineering, a new virus strain escaped from an allegedly “safe” trial station and entered the world at large.” To cover this up, the government has perpetrated one of the greatest hoaxes in history. Since writing this, Kurtz has transferred Smith Jones from the Parkin Institute to a facility for the criminally insane in Penetanguishene where he has disappeared into the system. Meanwhile, Kurtz himself has succumbed to the disease.

At the time of publication, Findley’s novel must have seemed outlandish. A dystopian world of child pornography rings? A global pandemic transmitted from birds? Conspiracy theories about how the pandemic was genetically engineered? Beliefs in cover ups and hoaxes? It all seems over the top, doesn’t it? And yet here we are, in a world where Prince Andrew has been accused of having sex with a minor procured by a pair of notorious sex traffickers. At the same time, a pandemic rages around the globe. And every weekend, if I choose, I can gather in Queen’s Park with the conspiratorial rabble who go on about cover ups and hoaxes. I have to pinch myself to see if I haven’t crawled between the covers of a dystopian novel and ventured upstream into Kurtz’s dark world.