I need to find a way to discuss certain books which I respect and which I view as brimming with literary merit but nevertheless despise. Among living authors, Haruki Murakami produces such books. I slogged my way through more than a thousand pages of 1Q84 and when I was done, scratched my head and wondered why he has such rabid fans and why each year the rumours swirl that this might be the year he gets the Nobel Prize. I couldn’t say precisely why I disagree with the prevailing opinion so I slogged my way through the more than six hundred pages of The Windup Bird Chronicle to see if that might change my mind. Instead, it merely confirmed my view that his preoccupation with a dark psychosexual mechanics has all the subtlety of a testosterone addled adolescent scribbling on the door of a public bathroom stall. Even so, I am not done with Murakami; I am not prepared to dismiss him out of hand. Although I don’t like his writing, I find him eminently readable.

I wonder if part of my attitude comes from my legal training which fosters compartmentalized thinking. I am like the defense counsel who knows his client to be guilty but nevertheless represents him to the utmost of his ability in service of higher aims. I cannot claim objectivity in my views; I cannot ground my opinion. The most I can say is that this is a matter of taste. I am obliged to acknowledge this and to further acknowledge that so long as I can appeal to nothing more than taste in my assessment of a work, then I have no cause to condemn it and certainly no cause to advise other readers to avoid what could prove for them to be a thoroughly rewarding experience. And so I enumerate my personal grievances, underscoring with each that it is, after all, personal, strongly influenced by my own experience, by cultural biases tied to whiteness and maleness that I scarcely have the insight to understand, and embedded within a literary edifice subject to its own biases a lifetime in the making. Alongside this acknowledgment, I would like to think I also carry a generosity of spirit that, like the presumption at the heart of legal process, assumes the best of those I critique.

Another author whom I willingly read even as I claim to despise his writing is Charles Dickens. Here, my distaste is not specific to Dickens but directed generally at Victorian novelists and, because it is directed generally, is more obviously a function of taste than of an objectively grounded theoretical claim. Although I inhabit a postmodern thought world, I was raised within modern sensibilities which itself was a reaction against Victorianism and late Romantic sensibilities. I don’t think it would be an exaggeration to say that I was raised to despise Dickens. Even to mock him.

Where does one begin? Let’s start with the mechanics of his writing. Dickens is notorious for his gloriously cumbersome and convoluted sentences, many of which can be held up as self-parody. Take, for example, this gem which appears near the opening of Chapter 42:

In one of those wanderings in the evening time, when, following the two sisters at a humble distance, she felt, in her sympathy with them and her recognition in their trials of something akin to her own loneliness of spirit, a comfort and consolation which made such moments a time of deep delight, though the softened pleasure they yielded was of that kind which lives and dies in tears—in one of those wanderings at the quiet hour of twilight, when sky, and earth, and air, and rippling water, and sound of distant bells, claimed kindred with the emotions of the solitary child, and inspired her with soothing thoughts, but not of a child’s world or its easy joys—in one of those rambles which had now become her only pleasure or relief from care, light had faded into darkness and evening deepened into night, and still the young creature lingered in the gloom; feeling a companionship in Nature so serene and still, when noise of tongues and glare of garish lights would have been solitude indeed.

Or this sentence near the beginning of chapter 54:

As he was not one of those rough spirits who would strip fair Truth of every little shadowy vestment in which time and teeming fancies love to array her—and some of which become her pleasantly enough, serving, like the waters of her well, to add new graces to the charms they half conceal and half suggest, and to awaken interest and pursuit rather than languor and indifference—as, unlike this stern and obdurate class, he loved to see the goddess crowned with those garlands of wild flowers which tradition wreathes for her gentle wearing, and which are often freshest in their homeliest shapes—he trod with a light step and bore with a light hand upon the dust of centuries, unwilling to demolish any of the airy shrines that had been raised above it, if any good feeling or affection of the human heart were hiding thereabouts.

Despite the prolixity of these two sentences and their obvious numerical contribution to the novel’s word count, I can’t imagine that the novel would suffer any harm if they were razored from the text and cast onto the garbage heap of literary history. In fact, the increased concision might improve the work. I can tolerate prolixity if it has a point, as in Tristram Shandy where the rambling digressions are the point, but not when its sole purpose is to lend heft to justify the purchase price of the magazine in which the story appears.

Another feature of Dickens’ writing which I find challenging is its sentimentality. While I admire him for taking up issues that we would today identify as social justice concerns—

• Sarah Brass has a maidservant, the “marchioness,” who is effectively a child slave;

• A coroner’s inquest determines (erroneously) that Daniel Quilp died by suicide and orders that his body be buried at a crossroads with a stake through the heart;

• Nell’s grandfather fears he will be consigned to a madhouse where inmates would, as a matter of course, be chained to a wall and whipped;

• Children in the novel are routinely given beer and spirits (in A Distant Mirror, Barbara Tuchman observes that beer was an important source of calories in medieval Europe; presumably that had not changed by the early 19th century)

—his presentation is undone by sentiment. The reader feels emotionally manipulated. It wasn’t until after Dickens that writers began routinely to exercise greater precision in maintaining a distinction between the authorial voice and the narrative voice, withdrawing the author to a greater remove and placing more trust in the reader to arrive at independent conclusions.

Related to this is the concern about didacticism and the way in which a heavy-handed voice (to mix a metaphor) enacts in the narrow relationship between author and reader the colonizing habits embedded in the broader relationship between the powerful and the subjugated. A shift in the way we frame the author’s role (or obliterate it altogether if we subscribe to Roland Barthes) sees it not as the summit of a hierarchy but as a facilitator amongst equals. The novel ceases to have designs upon the reader’s heart and mind and instead becomes a space in which the reader leverages personal insights which may be unique to that specific encounter and never occur again.

Finally, there is the neatness of the novel’s resolutions. In the final chapter, Dickens draws together all the stray threads. No fact remains unrevealed. No injustice remains unanswered. The novel stands as a practicum in theodicy: evil happens, and while we’re in the middle of it our narrow perspective may preclude our understanding why, nevertheless we can have faith that the author/god will work it all out to a higher end. We readers can take a similar assurance in our wider lives. This was all well and good for readers in 1841, but for those of us standing on the other side of 1858—the year in which Darwin published On the Origin of Species and began the squeeze on god from human affairs—such a theodicy is a tough sell, maybe impossible.

The Old Curiosity Shop is available for download as an eBook from the Gutenberg Project.

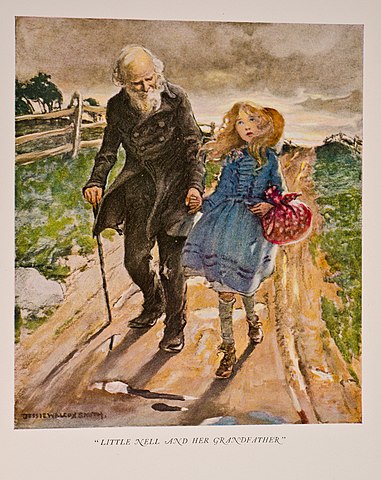

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain