Everybody: A Book About Freedom, Olivia Laing (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2021)

In the rarefied world of reflective non-fiction, Olivia Laing is something of a Mozart. This is more obvious when we compare her work to that of the countless Salieris clamouring beneath her feet. A comparison to one such hack will suffice: Malcolm Gladwell. This impresario of the grand idea follows a simple formula. He examines the data and pulls from it an insight that, apparently, no one else has ever bothered to note. This insight becomes the foundation for a sweeping proposition that explains everything from why my morning coffee is bitter to why white police officers don’t know how to talk nicely to Black motorists. Once he establishes the sweeping proposition, he proceeds with what he does best. He tells stories. He marshals a dozen gemlike anecdotes to illustrate his grand thesis, never mind that anecdotes are functionally useless as tools to interpret data (because anecdotes by their very nature refer to the specific while data addresses the aggregate). Even so, like a string of cheap melodies, the anecdotes entertain. The problem with Gladwell is that, more often than not, his love of a good anecdote does violence to the truth he’s trying to expose. Simply put, his formula doesn’t work, unless by “work” we mean “sell books”.

Olivia Laing takes a different tack which distinguishes her from most non-fiction writers today. She begins by posing questions and conducts a meandering investigation, associative in approach and aleatory in feel, that is not driven by pre-determined suppositions she feels compelled to prove but instead is lured on by a restless intellectual curiosity. We conclude not with some epiphanic rapture but with the recognition that the investigation of her initial questions has led us to a wider field of questions. Her first non-fiction book provides us with an apt metaphor for her approach: the river. In To The River, we amble with her down the River Ouse, not to its end, but to a place where it widens into the English Channel and, beyond that, to an ocean. The end humbles the investigation, just as the proliferation of questions overwhelms the modest inquiry that prompted the investigation in the first place.

In Everybody, the initial question seems almost childlike in its simplicity: what is this thing called my body? What does it mean to inhabit a body? And what is it in relation to me? Almost immediately, we note a marked difference between Laing’s writing and the writing of someone like Malcolm Gladwell. Laing has, um, skin in the game. She takes risks. She makes herself vulnerable by sharing how she is personally affected by the questions she poses. She opens with an account of a “body psychotherapy” in which she submitted to a sort of massage aimed at releasing blockages in her body. Later she mentions the first time she had sex (with a boy) and, in the final chapter, shares her slow dawning that she is non-binary. Meanwhile, in Talking To Strangers, a book whose endpoint is an elucidation of the Sandra Bland death, Malcolm Gladwell offers us no clue as to what, if any, stake he has in the matter. His theoretical construct is his sole concern. So much so that when he finally gets around to applying his theoretical construct to the facts of the Sandra Bland case, he seems incapable of entertaining the most obvious conclusion, that a white police officer could be a hateful bigot, plain and simple.

Because Laing’s aims are more modest and because she entertains no discernible attachment to grand explanations, in my estimation she makes a more trustworthy companion on such journeys. She opens by introducing Wilhelm Reich, a disciple of Freud who ultimately broke with his master, finding the strictures of psychoanalysis too confining. Lie on a couch and talk to a person who offers little by way of feedback? Reich came to feel that this neglected an entire dimension of human experience. He started his career in 1920’s Vienna as a young analyst who began to suspect that many of his subjects were carrying the memory of trauma in their bodies, not just in their psyches. He found Freud’s psychoanalysis frustrating because, once the subject had an insight, the process seemed to stop; there was no path forward that would allow the analyst to translate that insight into practical living. Reich came up with the idea of “character armour” to articulate the sense of blockage that subjects felt when they reached this impasse.

In 1930, Reich moved to Berlin which, until the rise of Hitler, was perhaps the most libertine locale on the planet. There, he developed the idea that the orgasm provides the necessary release to penetrate this blockage. Through physical experience, most notably sexual experience, the subject could complete the reintegration of the self in a way that psychoanalysis could only begin. In 1934, Reich introduced touch into his therapy, a shift that was absolutely forbidden by his profession. At about the same time, he published the book, The Mass Psychology of Fascism, which he had the dubious pleasure of watching go up in flames at a Nazi book burning. In 1939, Reich fled Berlin for New York. Laing writes: “By the time he arrived in America in 1939, he was convinced of three things: that there was a life force, which he called orgone; that it could become blocked because of emotional trauma or repression; and that these blockages had profound physical consequences.” He then proceeded to build the first of his orgone accumulators, wooden boxes in which the subject would sit as if in a sensory deprivation tank but without the comforts, and this was supposed to help remove blockages from the body. By the 1950’s, the US FDA got wind of his devices and, because he had failed to get approval, the FDA destroyed all his orgone accumulators. At the same time, FDA officials gathered up his writings and destroyed them, too. Anyone with a keen sense of irony will note that Reich received the same treatment in America that he received in Nazi Germany. Worse, in fact, because he received a prison sentence for his FDA violation and died as an inmate in 1957.

It is against the backdrop of Wilhelm Reich and his ill-fated orgone accumulator that Olivia Laing undertakes a wide-ranging survey of the countless ways we, as social creatures, find it difficult to deal with one another as embodied creatures. Violence against women. Second wave feminism. Abortion. Andrea Dworkin and Angela Carter. The right to die. Kathy Acker and Susan Sontag. Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. Nina Simone. Black Lives Matter. AIDS. Gay liberation. Prison. All our liberation movements can be regarded as struggles against problematised embodiment. And we can take this further. Laing is English and so has less occasion to come up against another category of embodiment that lives at the heart of England’s colonized territories: that of the Indigenous body. Once, this category was so marginalized, it didn’t even exist. To English eyes, these lands were empty, and so any bodies living upon them could safely be exterminated as, by definition, they weren’t real. Going further still, Laing completed her book as Covid-19 circled the globe, presenting a new challenge to our embodiment.

There is much about Covid-19 that merely intensifies our old habits. Children in cages. Border walls. The foment of anti-immigrant sentiments. Moral panic leading to the repeal of abortion laws. Missing and murdered women and girls. The murder of children in Gaza. The end of Hong Kong as we know it. The “re-education” of the Uighur. Forgive me if I’ve forgotten anything that has worsened under Covid-19. It all seems a blur. I don’t think Laing means to say anything in particular about all this except to trace some of the lines that have brought us to this point and to observe that, still today, power enjoys the upper hand and demands that our feeble bodies submit to its will. From time to time, liberative impulses light the way, but their beams have limited reach.

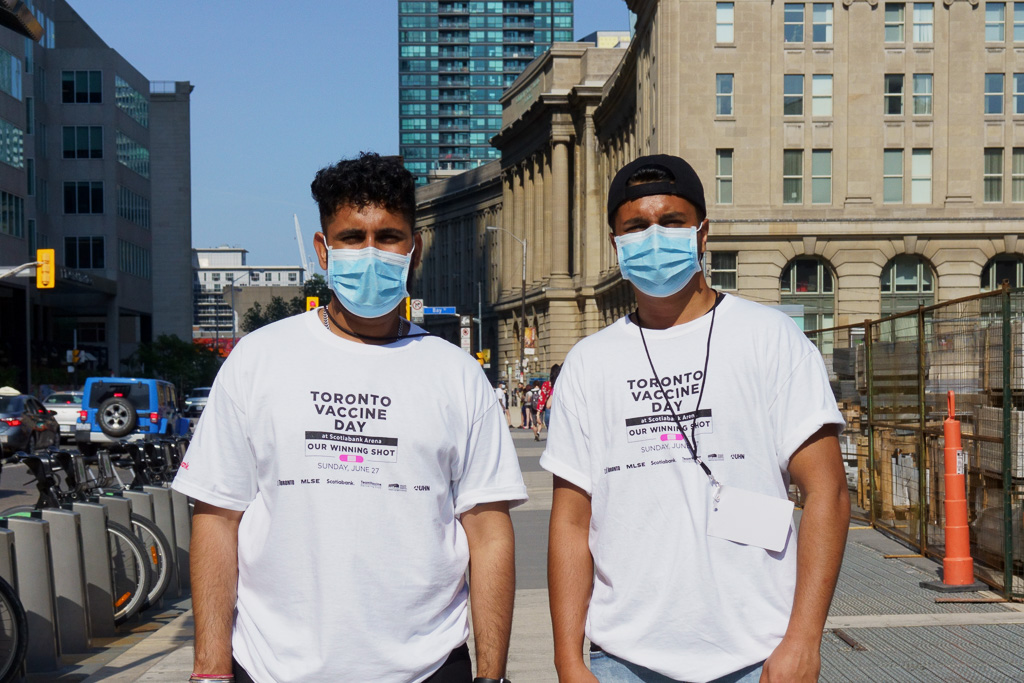

Let me conclude with a further observation about life during Covid-19. Something that concerns me in 2021 is an inversion I have witnessed in the way language is deployed in connection with freedom and liberative movements. The people one would normally think of as allies in liberative struggles, the nice middle-class liberals who adopt a live-and-let-live attitude towards issues like gay marriage and reproductive rights, now find themselves in the odd position of policing people’s bodies by enforcing mask-wearing and promoting vaccination. I say “odd” because, at least superficially, these actions engage people in impositions upon the body. Meanwhile, anti-mask and anti-vaxx protesters have co-opted well-known feminist mantras like “my body; my choice” to sew confusion by suggesting that their position has something to do with integrity of the body.

If I were Roland Barthes, I might suggest that the anti- people are exploiting a confusion that arises from the fact that a mask is an ambiguous signifier. It performs more than one function simultaneously. On the one hand, it is a prophylactic epidemiological measure: it’s practical function is to free us from disease. On the other hand, it is a symbolic article of clothing that signifies our oppression, first at the hands of disease and, by extension, at the hands of the state which mandates that we wear the mask. In its symbolic function, the anti- people treat a mask quite literally as an oppressive piece of clothing, like handcuffs or leg irons. In their approach to the interpretation of the mask’s meaning, they are no different than fundamentalist Christians who subject Biblical scriptures to all sorts of wild contortions. And yet, as the statistics demonstrate, those states that are more liberal (another of those strange inversions) in their mask rules have fared poorest in managing the pandemic.

Covid-19 has illustrated the importance of collective response in the face of pathogens. While we may have scruples about political theories of collective action, like socialism and communism, pathogens are incapable of political ideology and will continue to spread regardless of the wonks we cheer at rallies. While we have an understandable concern for the health of our individual bodies in all their vulnerability, we have a simultaneous obligation to maintain a concern for the body politic. The health of the collective body matters too.