We Are One: Poems from the Pandemic, edited by George Melnyk (Calgary: Bayeux Arts, 2020)

It wasn’t long after the pandemic began when I acknowledged, at least in the privacy of my own head, that the pandemic would likely eclipse all other global traumas since WWII. And it was not long after that when I realized the pandemic would drive much of our subsequent literature and art as we work our way through this trauma. And so I kept my eyes open for early signs of a shift in our literary output. In poetry, the first Covid-19 reference I stumbled upon was a piece titled “Hardwick” in Angela Carr’s 2020 poetry collection, Without Ceremony. A lesbian couple retreat from New York City to a small town in Vermont and there the poet wonders if it is “more dangerous to identify as a lesbian than as a potentially infected New Yorker…” It reminds me of a converse experience as a cis white man fleeing Toronto for rural Ontario and trying to pass as local. I think to myself: so this is a little taste of what it’s like to be closeted. In small ways, Covid-19 has given me unexpected opportunities to be more empathetic.

I found more Covid-19 poems when, in June, the Scottish Poetry Library posted its 2020 online anthology: Best Scottish Poems 2020. It does this every year, but its 2020 selections naturally gravitate towards Covid-themed poems.

When I cracked open the book and started in on George Melnyk’s forward, I was a bit startled to read his confession that “[t]his book contains poems of great sophistication and it also contains doggerel.” He reasons that “only by incorporating the brilliant and the humdrum and everything in between could the vast array of experiences related to the pandemic be authentically captured.” I scan the book and, true enough, some of the poems are wonderful and others are total shite. I had expected Melnyk, as editor, would act as a gatekeeper to keep chunks of poetic effluence from contaminating my pristine little pool. But no.

In his book, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, Oliver Burkeman opens with an informal experiment, asking people he meets to tell him, without pausing to think on it, how many weeks long they think the typical human life is. Invariably, the answers people give him are grossly inflated. That becomes the starting point for a reflection on the fleeting nature of human life. He encourages his readers to act as faithful stewards of the limited and ever-dwindling time at their disposal. The answer, it turns out, is four thousand weeks. Hence the title of his book. By the time most of us realize that we are, in fact, mere mortals, we have only two thousand of those weeks left to us. For someone like me, now in my late middle age, time has attenuated that number by another thousand.

As a committed book reader, I have another way of measuring the span of my life. Assuming I read an average of one book each week, then the balance of my life is one thousand books long, fifteen hundred if I’m lucky. In fact, I read more than a book each week, so, barring accidents or cognitive decline, my remaining life might prove to be two thousand books long. In my personal mythology, it isn’t three sisters who sit with the thread of my life between the blades of their scissors; instead, it’s a celestial librarian who kicks me onto the street and locks the door behind me. Without access to words, I cease to exist.

Given the realization that I have a finite number of books left to read in this life, it is becoming increasingly important that I be judicious in my reading choices. I still want to seek out fresh writers. But more and more I resent them if they waste my time with shitty writing. Recently, as part of its 30th anniversary celebration, CBC’s Writers and Company reposted the Eleanor Wachtel interview of Zadie Smith, Caryl Phillips, and Aleksandar Hemon. At least two of them said something to the effect that now that they are older and realize life is finite, they read sparingly, never leaping into a book on spec, always relying on trusted recommendations, preferring to revisit favoured familiar texts; the demands of writing severely curtail their reading. Essentially, they rely on the curatorial function of critics and editors to help them act as responsible stewards of their limited supply of weeks.

Imagine my surprise then when I read George Melnyk’s forward to We Are One and find that he takes a completely different view of his role as editor. He doesn’t make it clear what he thinks he’s doing. Maybe he treats poetry as cultural anthropology, throwing everything into the pot because, good or bad, it’s an important measure of the times. Or maybe he treats poetry as that biological goop scientists put in Petri dishes to grow cultures; the poetry may have no intrinsic value, but it provides a fertile base for our imaginative lives. I toy with these possibilities but return to my natural assumption that editors are supposed to act as filters who let only the good stuff get through.

Maybe I’m being too precious about my reading. Maybe I’ve allowed Covid thinking to infect my word-bound brain. I want to keep my cranium safely quarantined so that only pre-screened literary thoughts swim between my synapses. I won’t put my sensibilities at risk of contamination by violating poetry’s version of the social distancing rule. No mucking around with raw unpolished lines for me. I want my lines to be safely masked. Better yet, I want them to present editor-approved vaccine passports. Maybe I’ve allowed anxiety—especially around my dwindling supply of weeks—to get the best of me. So I shut myself up in my private wordy world and pretend I can live indefinitely in this state of self-isolation. Except, of course, poetry isn’t a pathogen and those like Melnyk who share it with enthusiastic abandon aren’t anti-maskers.

Melnyk divides the poems he received into eight different categories each reflecting an aspect of our shared Covid experience: family, nature, distancing, fear and quarantine, isolation, grief, resilience and reverie, love and laughter. I think one of the reasons some of these poems are “doggerel” or—in my words—total shite is that they were composed too close to the trauma they address. Take grief, for example. The latest poems in this anthology were written in October, 2020. Now, more than a year later, we find ourselves still in the pandemic’s grip; it’s become big and unruly; we’re only now coming to see that this may be a chronic state, that there may be no return to the way things were. In October 2020, we barely knew what it was we were grieving. It’s almost inevitable, then, that any expression of whatever it was we were feeling back then comes off now sounding half-baked.

Another problem with writing too close to the trauma is that we feel compelled to name our feelings and experiences and to go on at length about it, like the person struck by a car who needs to tell us over and over again what happened. While it is natural and understandable to respond to trauma in this way, these impulses tend to undermine the things that turn our ordinary words into poetry. The explicit naming of feelings and experience offers a degree of literalism that plays well in journalism and televangelism but, as pornography’s second cousin, it isn’t exactly subtle. And the attendant logorrhoea works against some of the things that make poetry most interesting, compression, ambiguity, multivalence.

Finally, there is the preoccupation with what I like to call the “really real.” During the pandemic, shit happened. We all know shit happened. We read about it in the news or clicked on links in our social media feeds or gossiped about it when we were Zooming with our colleagues. People died alone. Military personnel developed PTSD after attending Long Term Care disaster zones. Health care workers held up iPads so the dying could say good-bye to loved ones. Toilet paper fights. People spitting on produce in grocery stores. There is a pervasive attitude that valourizes the “really real”. Our writing is legitimized in part by the extent to which it draws upon the grittiest corners of lived experience. And yet, if we were to subject our lives to the same statistical analysis we apply to our pathogens, we’d find that most of us most of the time lead uneventful lives. We’re too busy self-isolating to risk exposing ourselves to anything remotely approaching the “really real.” In statistical terms, almost nobody experiences the pandemic as a series of dramatic events; the vast majority of us experience it as long stretches of boredom and loneliness. The poetry here over-represents the “really real” while most readers seek solace for a different kind of trauma: the overbearing presence of the great nothing that has taken hold of our lives.

____________

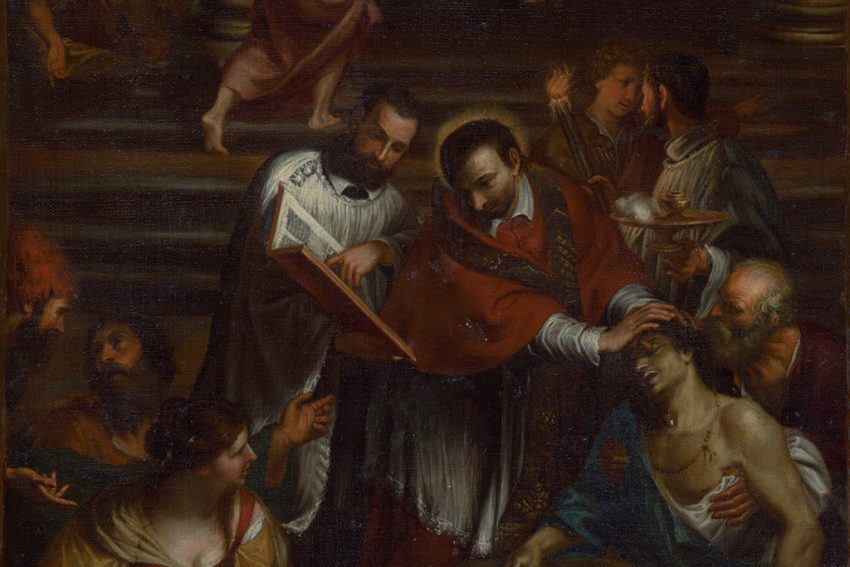

Photo Credit: Saint Charles of Borromeo among Plague Victims, by Giovanni Bonaiti (Wikimedia Commons)

Thank you for reviewing this book. Your review suggests a second volume is in order that captures the second year of the pandemic. Since you feel it is too close to the moment to have a true perspective a third volume in a couple of years might help.