My wife is Chair of the Board of Directors for the Orpheus Choir of Toronto. She sings alto, I sing tenor. Ordinarily, we gather with 60 other like-minded musicians once, sometimes twice, a week, and offer up four concerts each year along with other “extracurricular” engagements. This year has presented my wife with a fresh set of challenges. It began early in March with the question of whether or not to continue rehearsals. With the March 11th WHO declaration that Covid-19 is a pandemic, we cancelled rehearsals but hoped there might still be time to mount our May concert if we resumed rehearsals by, say, mid-April. It quickly became apparent that we wouldn’t be gathering again this season and so we announced the cancellation of our final concert.

This is particularly poignant for many of us because the concert was set to coincide with Mental Health Awareness Month. We had commissioned a work by Allen Bevan that promises to be a stunning addition to secular choral repertoire. We had hoped that our May concert would reach many people who struggle with mental health concerns. My wife agonized. Our choral director, Robert Cooper, agonized. In fact, agonizing seems to be the word that characterizes the mood of all arts organizations these days. We have planned a full 2020/21 concert season, going through the motions, but knowing full well that we are unlikely to resume until 2021. The Board has made no formal announcement about the next season, but the agonizing continues.

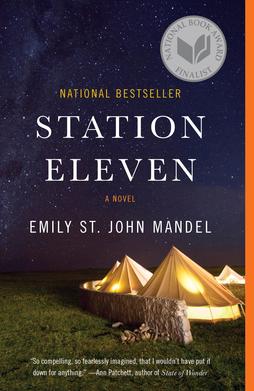

The latest instalment in my pandemic reading list speaks to all arts organization who find themselves in a state of limbo: Station Eleven, by Emily St. John Mandel. Station Eleven imagines a post pandemic post apocalyptic world so ravaged by disease that all social order has evaporated. Notwithstanding the Hobbesian nature of their existence, a band of actors has joined with the vestiges of a symphony orchestra to establish the Travelling Symphony. It passes through small communities of survivors and entertains them by staging Shakespeare’s plays and performing instrumental music. One of the players, Kirsten Raymonde, has placed a tagline on the lead caravan: Survival is insufficient. She also carries the line tattooed on her left forearm.

Kirsten’s line comes from episode 122 of Star Trek: Voyager titled “Survival Instinct.” In the episode, the former member of the Borg Collective, Seven of Nine, is faced with a conundrum. She has escaped from the Borg Collective and has recovered a sense of individuality with its attendant feelings of freedom and loneliness. Three more members of her matrix have tracked her down and want her to help them achieve individuality too. However, this turns out to be impossible. Her comatose colleagues can be revived as individuals, but will survive for only a month. Alternatively, Seven of Nine can return them to the Borg Collective where they will be re-assimilated as drones who live out a natural lifespan but without any sense of individuality or freedom. Seven of Nine decides to revive them, reasoning that it is more important for them to enjoy the fullness of human experience, however fleeting, than to have a long but pointless existence. Survival is insufficient.

Kirsten decides that one could do worse than Star Trek for a code to live by, which is mildly amusing given that she devotes her life to performing Shakespeare. She and a friend named August find themselves separated from the Travelling Symphony and, following agreed-upon protocol, make for the group’s destination. In this case, the destination is a town called Severn where there is rumoured to be a Museum of Civilization. In fact, the Museum of Civilization is the grandiosely named effort of a single man named Clark Thompson who, twenty years earlier, found himself stuck at the Severn City Airport when the pandemic broke out, and in the aftermath, began to collect and exhibit items to stave off the boredom. As with the Travelling Symphony, Clark’s Museum of Civilization is gloriously useless and yet somehow essential.

So often, politicians and corporate wonks treat the cultural sector (even the phrase “cultural sector” makes me queasy) as if it’s fluff. It has value only to the extent that it can fold itself inside a utilitarian rationale as, for example, an alternative to welfare or an advertising opportunity for corporate sponsors. This seems especially true when they get it in their heads to implement austerity measures. Think Reaganomics or Thatcherism. Closer to home, in Ontario, we had Mike Harris and his Common Sense Revolution. Most recently, we have enjoyed the pleasure of Doug Ford who defunded health care, education, and the Ontario Arts Council almost immediately after he got elected on his Buck-a-Beer platform.

Unfortunately for the small-government pro-business ideologues, Covid-19 has created something of an economic laboratory generating tangible evidence that there are certain elements of our lives for which the private sector is utterly ill-equipped. Delivery of health care, for example. People have suddenly figured out that a generously funded publicly administered health care system might be a good idea that saves countless lives. And as people self-isolate with school-aged children and are forced to become more active in their education, they have suddenly figured out that a generously funded publicly administered education system might also be a good idea. And, in the same way, as they sit watching locally developed programming like Schitt’s Creek and reading novels and listening to music, people are suddenly discovering that a life devoid of a “cultural sector” is an empty life indeed.

With imagination and heart, we will find fresh ways to give expression to our creative impulses, whatever the medium. Survival is insufficient.