An April 14th article in Hollywood Reporter has photographers reevaluating their online practice. The article reports on a law suit in which photographer, Stephanie Sinclair alleged copyright infringement against Mashable, the online tech news outlet owned by Ziff Davis. A US Federal Court judge disagreed and found in favour of Mashable. The facts are not in dispute. Sinclair had posted a photo to her public Instagram account. Mashable contacted her in relation to a proposed article titled “10 female photojournalists with their lenses on social justice” which it posted on March 19, 2016. They offered $50 to use Sinclair’s image. Sinclair refused the offer. Mashable used the image anyway by embedding the Instagram post. Sinclair claimed that this was a violation of copyright law. The judge who tried the case found that because Instagram’s Terms of Use grant to Instagram “a non-exclusive, fully paid and royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license to the Content,” Mashable, as a sublicensee, was entitled to embed Sinclair’s photograph in its article without compensation.

Although I am a lawyer by training (non-practicing), I am absolutely unqualified to comment upon the merits of the decision, and have no qualifications to comment upon US copyright law. Nothing I say here can or should be construed as legal advice.

There are only two matters I want to address neither of which has any legal import:

1) The decision is absolutely unsurprising within the current US political and economic climate. Look at the relative power of the parties. The plaintiff, Stephanie Sinclair, is a private individual with a camera. The defendant is an online media portal which Ziff Davis purchased in 2017 for $50 million. Ziff Davis had been purchased by J2 Global in 2012 for $167 million. As of April 15th, 2020, J2 Global’s market cap is valued at $3.625 billion. All figures are in US dollars.

The myth that grounds American copyright law is that it serves the little guy, the garage band working up original material for its next gig at the local bar, the novelist banging out a couple pages each night between shifts at Walmart, the Starbucks poet hoping to break out as the next Bob Dylan. They make it big and copyright protections allow them to cash in on their success. The underlying narrative is appealing and quintessentially American, but, like the winning lottery ticket, it reflects almost nobody’s reality. Every year, personal autonomy in the arts suffocates a little more as corporate interests suck more oxygen out of the creative atmosphere.

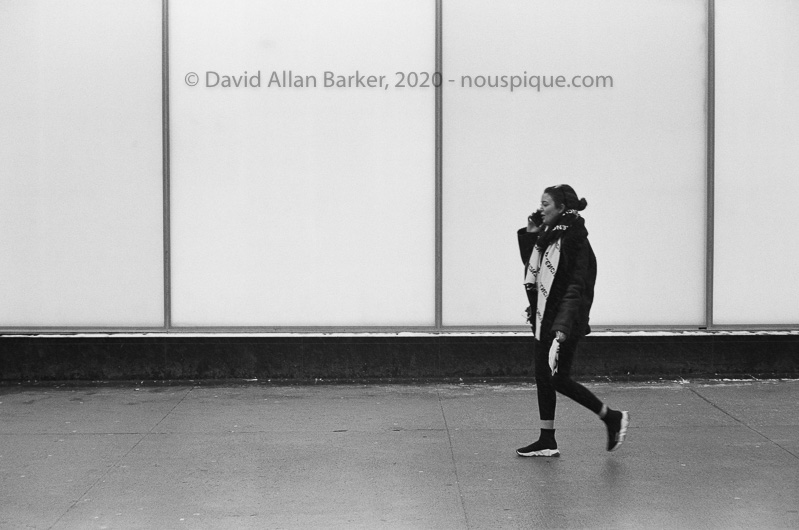

2) Whatever the underlying legal reasoning, decisions like this have a practical effect on personal behaviour. To put it more bluntly, they have a chilling effect by producing perverse incentives. So, for example, some photographers may stop using Instagram as a platform. The problem here is that it is difficult for photographers to garner attention without resorting to social media platforms. Leaving a platform can feel like professional suicide. A more viable approach is to use watermarks. Although much maligned because they are visually annoying, they nevertheless declare with absolute certainty who holds rights in a given photograph. I am undecided about their use.

For now, my personal approach is softer. First, I use my own domain and my own server as the primary online repository for my photographs and other digital creations. Second, I prefer to use platforms that allow me to link directly to my posts e.g. Twitter, Vero, Ello, Flickr. Instagram is clunky because it doesn’t allow for direct links. The only way I can get IG followers onto my site is to direct them to my bio link. Third, I churn Instagram content to disrupt embedded links. I do this by regularly archiving or deleting posts. Typically, followers don’t engage with posts that are more than a day or two old, so I don’t sacrifice much by deleting older posts. Besides, if I want to develop an online portfolio, I owe it to myself to develop it in a space I control.