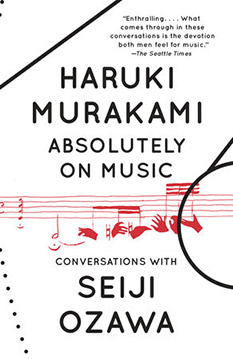

The following post is in no way a book review; more like notes scribbled while reading.

Absolutely On Music is a series of conversations between novelist Haruki Murakami and conductor Seiji Ozawa. I was too young to remember when Seiji Ozawa was conductor of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra (1965-1969). My earliest experiences going to the symphony involved first Victor Feldbrill and then Andrew Davis. They performed in Massey Hall until 1982 when the TSO moved to Roy Thomson Hall where Andrew Davis continued until 1988. Ozawa of course conducted in Massey Hall which he describes as Messy Hall because of its muddy acoustics.

Naturally, I most enjoyed his reminiscences about Toronto. The book devotes significant print to Glenn Gould in part because Ozawa witnessed a famous encounter between the young Gould and Leonard Bernstein. Gould was going to perform Beethoven’s 3rd Piano Concerto with the New York Philharmonic and Ozawa was assistant conductor at the time. Gould had his idiosyncratic way of doing things and refused to adapt his performance to Bernstein’s style of conducting the orchestra. When you think about it, it was pretty ballsy of Gould to stand up to Bernstein. This was 1959 and he was only 27 years old. Such confidence! Such cockiness! Bernstein took the unprecedented step of addressing the audience before the performance and confessing that they were at an impasse. Nevertheless, he would not abandon the performance; Gould’s interpretation was sufficiently interesting that the audience deserved to hear it. I suspect one of the things that saved Gould was that he could articulate why he did what it did which satisfied Bernstein that he was not simply being a rebellious kid.

As the pair listen to a recording of the concerto, Ozawa says: I heard all kinds of weird stories about him when I was music director of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. He invited me to his house too… Then Murakami interjects with a curious editorial note:

Murakami note: Unfortunately, some of the anecdotes revealed at this point cannot be committed to print.

Are you fucking kidding me?!? This is the only time in the entire book that Murakami self-censors.

This is precisely the set-up the imagination needs to run wild. What did Ozawa and Gould do together? Go on a drunken rampage through the city streets? TP Victor Feldbrill’s home? Share a woman in a whorehouse? Puke their guts out on Shuter Street? Roll a homeless man just for kicks? Go to Yorkville and smash Joni Mitchell’s guitar? Leave smouldering feces in a paper bag on Anne Murray’s doorstep? What? What could possibly be so bad they can’t commit it to print?

Along the way, Murakami indulges in an interlude reflection on the relationship of writing to music. Speaking from his own experience, he observes that “[t]he two sides complement each other: listening to music improves your [writing] style; by improving your style, you improve your ability to listen to music.” He then goes on to expound upon the importance of rhythm as an essential quality of good writing. I wish he’d given more attention to tone. In tone—the theorizing, the need to give a full account—the passage reminds me of Murakami’s explanatory fetish which blossoms most fully in his novel, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. He seems incapable of simply letting a thing be, but must flog it with a full accounting until it is dead. I prefer Geoff Dyer’s non-fiction; he rarely succumbs to the theorizing temptation.

I encountered an interesting passage on page 129. Murakami is once again indulging his explanatory fetish, trying to account for the fact that, although only in his twenties, Ozawa (who had little English or German) was able to lead major Western orchestras under the mentorship of Bernstein and Karajan and successfully communicate his wishes to their orchestras. He suggests that while many Japanese musicians are technically proficient, few ascend to the highest ranks because “they rarely communicate a distinct worldview. They don’t seem to have a strong determination to create their own unique worlds and convey them to people with raw immediacy.” Ozawa agrees and warns that if you do not do this, what you produce is elevator music.

The passage stands out because I frequently hear the same comment from the director of the choir I belong to, the Orpheus Choir of Toronto. Robert Cooper sometimes has to jolt us from our complacency by reminding us that our singing must be informed by a point of view; we are conveying more that just music. I asked Bob if he had read Murakami’s book and while he hasn’t, he suggested that this is probably a widely circulated bit of wisdom. Nevertheless, to hear these words from Ozawa gives Bob more credibility in the face of doubting choristers. Anyone can sing the notes; what sets a singer apart is the capacity to sing a philosophy of life.

Later, Murakami and Ozawa apply the “distinct worldview” theory to a specific set of facts: the music of Mahler. This leads them into a synaesthetic moment. Ozawa tells how, thirty years earlier, he went to art galleries and explored the work of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, reasoning that an understanding of visual art from the time and place would aid in understanding Mahler’s music.

Personally, I’m skeptical. Mahler is a generation older, a late Romantic. Klimt and Schiele are kids, maybe early Abstract Expressionists. If there are lines of influence, they run from Mahler to the artists and not the other way around. In fact, I note that Klimt attended Mahler’s funeral so, presumably, he knew Mahler’s music or attended the operas he conducted. Mahler died in 1911 and both artists died in 1918 thanks to the flu pandemic which swept through Europe.

It might be best not to think in causal terms when considering lines of influence but, instead, to acknowledge a broader sweep that caught up all the arts; the rise of nationalism which was the dark underbelly of Romanticism and ultimately led to the so-called war to end all wars, the industrialization of death, and the rise of a major pandemic. Those experiences found expression in all the arts. So I think it would be valid to suggest that exploring the worldview reflected in one area of the arts would illuminate the worldview reflected in another. But causation would be a more difficult case to make.